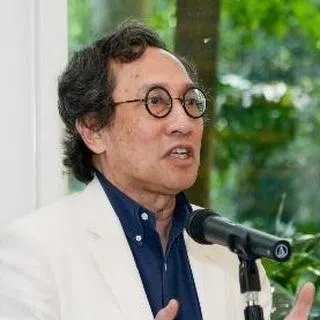

Bilahari Kausikan: What does the American presidential election mean for Singapore and Asia?

Former permanent secretary of the Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs Bilahari Kausikan shares his thoughts on the US elections, reflecting that the big pieces of US policy in Asia are already in place and are unlikely to change regardless of who wins. In that light, Singapore and Asia will find a way of working with whoever occupies the White House.

On the eve of the US election, the race looks like it will be a photo finish. It is pointless to try to predict the winner, although American bookies are giving odds on Trump. We don’t get a vote, so it’s more useful to look at what the elections mean for us regardless of who will occupy the White House.

First, what the elections do not mean for us. This is not the apocalyptical contest over the future of American democracy that some — mainly Americans and Europeans — make it out to be. America is resilient and even in my own lifetime, I have seen it regenerate itself more than once. My American friends may be right about the threat to their democracy. But few if any Singaporeans, or Asians in general, regard the American variant of democracy with unqualified admiration, nor do we recoil in Pavlovian horror from every variant of authoritarianism. I sympathise with my American friends, but their concerns should not be our main concerns.

Pragmatism rules

Singapore and Asia have always structured our relations with the US more on the basis of common interests than common values. This is true of formal US allies as well. We are pragmatic. There is only one America which plays a vital and irreplaceable role in balancing China and maintaining stability in Asia — a role that is now acknowledged by traditionally non-aligned countries like India and Indonesia and even old enemies like Vietnam — so we will find a way of working with whoever occupies the White House.

Second, let’s see things in perspective. The Trump administration wasn’t all bad. True, his walking away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was a shock that still reverberates, but we adapted through the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The world did not end. And some of the things Trump did to restore the credibility of American hard power were certainly in our interest. To give just one example: in August 2017, Kim Jong-un got carried away and threatened Guam with his missiles. Trump responded by threatening to rain “fire and fury” on Pyongyang. Since then, as far as I can determine, North Korea has never tested any long-range missile on a trajectory that takes it anywhere near Guam.

... there is not very much that separates Biden’s consultative approach from Trump’s transactionalism — call it “polite transactionalism”.

Obama made prettier speeches, but Trump understood — perhaps instinctively — hard power better. And the most dangerous issues in our region where accidents are most likely to get out of hand, are all hard power issues that need to be managed by credible deterrence.

Biden’s ‘polite transactionalism’

Nor was the Biden administration all milk and honey. True, he was much more consultative and predictable and that’s all to the good. But let’s not forget that Biden was not consulting you to enquire how your family is doing, but to see what you are prepared to do to advance America’s strategic goals.

After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, America faces no existential threat anywhere in the world. So there is no compelling reason for the US to “pay any price, bear any burden” to uphold international order. This is not an America in retreat or returning to isolationism that some have portrayed. But it is certainly an America that is going to be more discriminating in how and whether it intervenes and thus one that will demand more of its allies, partners and friends. In this respect, there is not very much that separates Biden’s consultative approach from Trump’s transactionalism — call it “polite transactionalism”.

Failure to adapt quickly enough to the new strategic environment defined by enhanced US-China rivalry and a more (politely) transactional US reduced ASEAN’s usefulness and marginalised ASEAN.

ASEAN’s ‘centrality’ eroded

Negotiations over Biden’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) were difficult, and in the end no agreement was possible over the trade chapter. ASEAN has not fully understood the similarity between Trump and Biden and so its “centrality” continued to be eroded. At its core “centrality” means being useful. Failure to adapt quickly enough to the new strategic environment defined by enhanced US-China rivalry and a more (politely) transactional US reduced ASEAN’s usefulness and marginalised ASEAN. Just because someone calls you “central” doesn’t mean they — China as well as the US — really mean it.

Third, the big pieces of US policy in Asia — the approach to China and trade — are already in place and are unlikely to change in any fundamental way regardless of whether Trump or Harris wins. Changes are likely to be on the margins of China and trade policy rather than at their cores.

Of course changes on the margin — as economists know — can be very important and disruptive, so it is worthwhile to examine what those changes may be.

... undue emphasis on human rights will complicate the relationship with China and ASEAN.

Taiwan Strait

The most dangerous flash point in our region is in the Taiwan Strait. Trump is unlikely to be as supportive of Taiwan as Biden but that is not necessarily bad. Biden’s four statements clearly supporting Taiwan in the event of a Chinese attack are an aberration in US policy since the US and the PRC normalised relations in 1979. They have bred a sense of entitlement in Taiwan. The attitude in Taipei is “I am the only Chinese democracy so you must help me”. This can be dangerous if it leads Taiwanese politicians to push the boundaries too far.

Harris is more likely to emphasise values and human rights in her foreign policy and this might encourage Taiwan’s sense of entitlement. In any case, undue emphasis on human rights will complicate the relationship with China and ASEAN.

US attitude to trade has fundamentally changed

Let me now turn to trade. But again, first some perspective. China is an important economic partner and will grow in importance. But the US remains important too. In 2023, the total volume of China’s trade with ASEAN was US$696.7 billion while the figure for the US was US$395 billion, quite a disparity. But if you add in trade with US allies — the EU, Japan, the ROK and Australia — the volume of ASEAN’s trade with the West amounts to US$804 billion.

Trump says “tariff” is his favourite word. He has threatened to levy “automatic” tariffs of 10 to 20% on every US trading partner and 60% or more on goods from China and perhaps as high as 1000% in some circumstances. The upper range is probably hyperbolic but it would be prudent to assume that some degree of tariffs will be imposed. Again the world will not end but the world economy, already fragile in some respects, will certainly slow even if it does not collapse.

Another Trump administration will almost certainly be tougher on Chinese goods using Southeast Asia (and Mexico) as a “backdoor” into the US and Chinese companies “Singapore-washing” themselves. It is not that a Harris administration will ignore these issues; she may not pursue them with the same sharpness, but pursue them in some way she will. We have to understand that the US attitude towards trade has fundamentally changed and adapt ourselves to the new reality.

More often than not in world history, it was the rivalries and the effort to mitigate — not erase — the risks that constituted the only “order” we knew.

Threat of conflict inherent characteristic of international relations

I don’t think globalisation can be reversed, although it will certainly become more patchy than it already is. The age of hyper-globalisation is over just like the age when interest rates were zero or near zero is over. The broader point is that we should not mistake the exceptional for the norm. The 20 or so years after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 were good years for us as for most countries, but that does not make them any less exceptional or replicable. We have returned to normalcy.

Rivalry between major powers and hence conflict or at least the threat of conflict are inherent characteristics of international relations between sovereign states. Of course US-China rivalry and the horrific wars in Ukraine and Gaza generate uncertainties and risks. But they are what the late Donald Rumsfeld called “known unknowns”. It is a fundamental mistake to think that any international order needs to be the result of consensus. More often than not in world history, it was the rivalries and the effort to mitigate — not erase — the risks that constituted the only “order” we knew.

That was certainly the case for at least almost half of Singapore’s short history. We not just survived but prospered under far worse conditions — don’t forget the Cold War was hot in Southeast Asia — with far less capabilities. What we did before, we can do again provided we keep our heads and pull together. The key challenges we face are domestic not international. The US election is important for everyone, but even more important is maintaining faith in our own agency and our social cohesion.

The Chinese version of this article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “比拉哈里:美国总统选举对新加坡和亚洲有何意义?”.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)