Wang Gungwu and Malaysia: Building an intellectual bridge to China

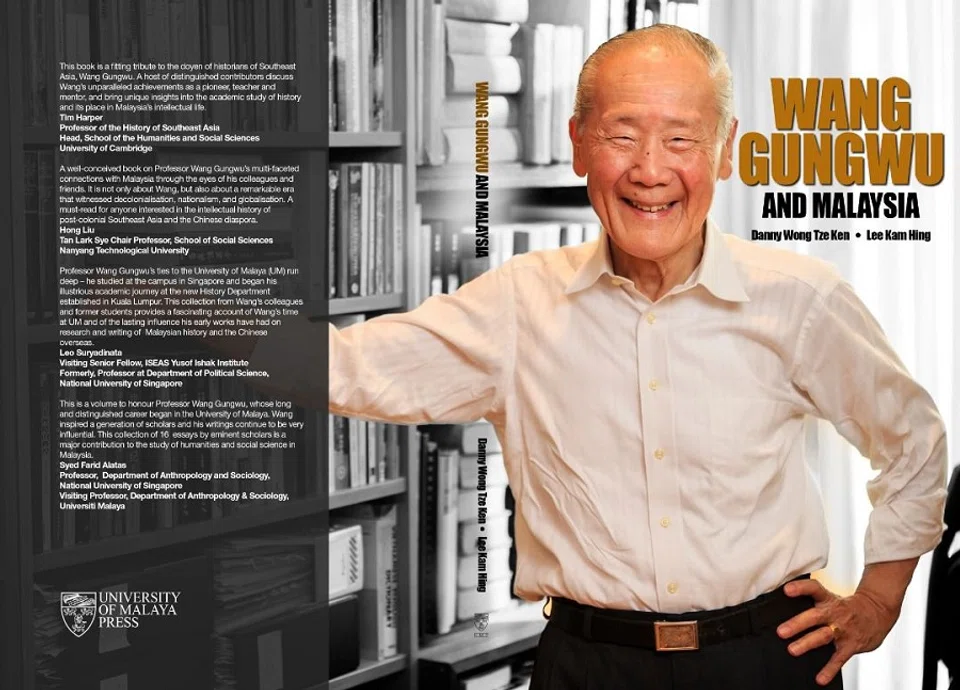

Tracing the evolution of China's development, Malaysian academic Peter T.C. Chang pays tribute to historian Wang Gungwu and his contributions to the study of Chinese overseas. Wang continues to play a major role in the field as a member of a pioneering class of bridge-building scholars who are adept at explaining China to the world, and the world to China. This is an edited version of the book chapter "A Pioneering Class of Bridge-Building Junzi" from the book Wang Gungwu and Malaysia (2021) published by the University of Malaya Press.

Wang Gungwu is a product of his time - a historic period in which China and the world were undergoing unprecedented transformation. A sojourner in his own right, Wang's intellectual complexion and temperament were shaped by the multiple milieus he traversed and embodied: the Chinese, the Southeast Asian, and the West. As a child of immigrants, Wang represented a new generation of overseas Chinese scholars imbued with a multicultural ethos and cosmopolitan outlook. This chapter is a study of Wang's remarkable accomplishments, as a pioneering class of bridge-building junzi (君子, scholarly gentlemen) equipped with a set of skills vital for explaining China to the world, and the world to China.

We begin with a review of how as a self-contained power, imperial China, was mostly indifferent towards the outside world. As such, the Sinic civilisation, despite its longevity, was impenetrable to many. And it fell upon foreigners, Westerners especially, to make the East comprehensible to the rest. The inward-looking Chinese world only started turning outwards during the late 19th century waves of migration, when a rank of overseas Chinese intellectuals, including Wang, emerged to engage the world. Wang's early research provided the world with the then rare Chinese insights into a still inward-looking China mired in domestic turmoil.

Then, Deng Xiaoping set the unprecedented trajectory of opening up the People's Republic of China (PRC) as the country could ill afford self-isolation anymore. Beijing sought to integrate itself into the global order and for the first time in its long history, China launched an extensive effort to make itself understood to the world. The Chinese state-directed campaign did not diminish the overseas Chinese role. Rather it accentuated the latter's own unique transformation. No longer subjects of the PRC, these Chinese abroad remained a vital conduit linking China to the non-Chinese world. And as will be elaborated below, this distinctive transnational multicultural bridgeway is foremost captured in the life and work of Wang Gungwu.

...imperial China was a reclusive, if not an isolationist, world power.

A historical review: the insular China

With a purported 5,000 years of history, China is widely acknowledged as one of the longest surviving human civilisations. According to the German philosopher Karl Jasper, Confucianism is one of the Axial Age traditions that transcended the then pervasive ethno-religious tribalism in order to advance universal humanity. About 2,500 years ago, separate yet in unison with seminal thinkers from the Greek philosophic domain, religions of the book transition and the Buddhist civilisation, the Confucian sages foresaw an inclusive moral community that embraced all humankind, regardless of race.

These universal aspirations, notwithstanding the Confucian universe, remain comparatively parochial. Today, Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, for example, are global religions, represented in almost every continent of the world, with membership consisting of diverse ethnicities. Confucianism by contrast is still a regional phenomenon, confined to Northeast Asia and remains largely a Han-centric tradition.

The Chinese civilisation has generated few writings of consequence to shape the outsider's view of itself.

In fact, imperial China was a reclusive, if not an isolationist, world power. With the exception of the famed Zheng He's maritime expeditions during the 15th century, the Chinese dynasties hardly ventured beyond the mainland. Self-sufficient and content with exerting dominance from behind the Great Wall, the Chinese had little need and showed scant interest to initiate contact with the outside world.

Even so, to be sure, China's borders were not completely sealed off. Many from afar were drawn to the Middle Kingdom, and brought with them, among others, the Islamic, Christian and Buddhist creed, transforming the Chinese cultural and religious landscape. These traders and travellers introduced the world to China. And it was these same foreign guests that took China to the rest of the world. One of the most fabled is of course Marco Polo, whose travelogue acquainted the West to the Sinic world.

Those efforts notwithstanding, China remained a not-very-well-understood mystic power of the East. In fact, the world's perception of China has largely been formed mainly through the lens of foreigners. The Chinese civilisation has generated few writings of consequence to shape the outsider's view of itself. The most authoritative literature the outside world referenced to understand the Middle Kingdom was written by themselves, the non-Chinese. This in itself is not an issue. But China today is discovering that non-Chinese observations may not always comport with Beijing's own self-representation nor are they aligned with the country's national interest.

Chinese scholastic migrations

Although imperial China rarely initiated external contact, the Chinese people have had more open engagement with the outside world. Archaeological findings, dating back to the Tang dynasty, confirmed the existence of Chinese settlements of varying sizes, scattered across Southeast Asia, the Middle East and even northern Africa.

But it was from the late 19th century onwards that Chinese migration began to assume a larger scale. As imperial China suffered a war-ravaged transition into modernity, multitudes fled the mainland in search of a haven and fortune in the southern seas. Many eventually planted roots, and contributed to the post-colonial nation-building of their faraway adopted home.

And one intriguing episode in these dramatic changes is the story of the quintessentially Chinese school of thought, Confucianism.

This modern era mass migration marks a watershed moment in Chinese history. By virtue of its size, it was the Chinese world's most consequential encounter with the non-Chinese environment outside of China. Driven in part by the broader 20th century globalisation forces, these resettled Chinese started to engage the wider human family across ethnic, linguistic and religious boundaries. Theirs was a cross-cultural immersion that has left irreversible imprints on the texture of the Sinic civilisation. And one intriguing episode in these dramatic changes is the story of the quintessentially Chinese school of thought, Confucianism.

Turmoil at home forced a segment of the Confucian scholastic community into exile in neighbouring Hong Kong, Taiwan and Southeast Asia. Some ventured further afield, westward to Europe, Australia, and the US. This exodus marked a traumatic chapter in the venerated Chinese tradition. Ceremoniously expelled from the land of its birth, the Confucians were compelled to adapt to a foreign habitat, infusing the erstwhile Han-centric tradition with a more diverse complexion. This transformative process is encapsulated in the person of Tu Wei-ming, one of the key figures in this generation of displaced Confucianists.

Born in Kunming, raised in Taiwan and educated in America, Tu's academic development took place largely outside of China. His early works were primarily on elucidating Confucian philosophical thought, ethics and morality. Later, Tu expanded his efforts towards inter-civilisational dialogue specifically between the East and West. These exchanges widened the appeals of the relatively parochial Confucian tradition. The formation of an offshoot called "Boston Confucianism", for example, showed that Confucianism could be transmitted across geographical and cultural divides.

In these efforts, Tu played a critical role in rendering the Chinese civilisation palatable. At a time when the rest had to rely on the West to understand the East, Tu's scholarship offered an alternative - the Chinese's own account of the East. To be certain, Confucianism remains unfamiliar to most but Tu's writings were steps towards making this ancient Chinese philosophical tradition more accessible through the pen of a Han-Confucian scholar.

As a sinologist, Wang's scholasticism spans a broader scope in terms of discipline... But it was Wang's extensive research on the Chinese communities in Southeast Asia that is of the most significance in opening up the Chinese world to the rest.

Wang Gungwu

A contemporary of Tu, Wang Gungwu was part of the 20th century Chinese scholastic migration who played a similar trailblazing role. But Wang's accomplishments were shaped by distinct sets of personal experiences and historical challenges.

As a sinologist, Wang's scholasticism spans a broader scope in terms of discipline, covering Imperial China's history, modern China's trade and political ideology, and Chinese cultural heritages. But it was Wang's extensive research on the Chinese communities in Southeast Asia that is of the most significance in opening up the Chinese world to the rest.

Over time, this coexistence turned into an immersion, as the Chinese migrants metamorphosed into a multicultural and multireligious community.

The largest grouping outside of the mainland, the Chinese in Southeast Asia are also the most diverse. Spread across a vast maritime archipelago, these Chinese immigrants found themselves navigating through a sea of variegated tongues and belief systems. To survive, they learnt to carve out an existence in this potpourri of distinct ethnicities (Malay, Thai and Filipino) and religions (Islamic, Buddhist and Christian). Over time, this coexistence turned into an immersion, as the Chinese migrants metamorphosed into a multicultural and multireligious community.

In Wang, we see the embodiment of this lively transformation. Born in Surabaya and raised in Ipoh, Wang's early formative years were cultivated in the rich backdrop of the Malay environment. Though interrupted by war, a brief undergraduate study in Nanjing helped reinforce his Confucian heritage and Chinese pedigree. Wang continued his education at the University of Malaya, and later secured his PhD from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. Upon completion of his tertiary studies in England, Wang embarked upon an illustrious university career that included stints in Malaysia, Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore.

...like Tu, Wang's pioneering scholarship was opening new windows for the world to gaze into the Chinese milieu, and this time through the framework set up by a native Chinese academic.

Wang's groundbreaking work on the overseas Chinese is thus as much a self-reflective exercise as it is an academic endeavour. The studies provide critical insights into the Chinese immigrants' experience, tackling the strains of acculturation and cultural identities, and the pain of divided loyalties and political allegiance. These are breakthrough studies, as there was barely any prior research conducted on the overseas Chinese. More pertinently, like Tu, Wang's pioneering scholarship was opening new windows for the world to gaze into the Chinese milieu, and this time through the framework set up by a native Chinese academic.

This came about when the PRC was still mired in self-imposed lockdown. Any crevice through which the world could peek into the hermit-like state was mostly filtered through the lens of foreigners. Wang's insights were crucial alternatives, providing the rare Chinese insight into the then imperceptible, introverted regime. Today, China has stepped out from behind that bamboo curtain, and the world has greater access to the Middle Kingdom. Even so, the PRC's image abroad continues to suffer misperceptions at best. This is a longstanding problem aggravated by Beijing's recent strategic turn towards adopting a more active and extensive global presence.

Modern China's global outreach

In 1978, Deng Xiaoping enacted the reform and opening up policy, compelling China to reach out and engage the world in order to recover from decades of economic stagnation. This is a seismic shift in outlook: China can no longer afford to stay reclusive, hidden behind the Great Wall. Chinese migrants have of course traversed the seas for centuries. But Deng's initiative was different; this time it was the Chinese state taking the monumental decision to open the floodgates and venture abroad. Not since the Ming Dynasty has such an extensive international outreach been undertaken by any Chinese government. And the present-day expedition is unprecedented in scale with far-reaching ramifications.

The Belt and Road Initiative is a case in point. Launched in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, the magnitude of this intercontinental infrastructure masterplan is unmatched in world history, heralding China's ascension as an economic superpower. Chinese high-tech giants such as Huawei and Alibaba are also providing global leadership in the next wave of digital revolution.

China's pre-eminence is not confined to the socioeconomic sphere. The US, the incumbent superpower, has labelled the PRC as a distinct civilisational force that could fundamentally undermine the existing world order in an adverse depiction that is fuelling "China the existential threat" narrative. For many in the West, this trepidation is underpinned by a deep-seated fear of the unknown, namely, an inscrutable China. And this negative sentiment permeates the Western-centric global media, often casting China's rise in terms with ominous undertones.

The Chinese felt at best misunderstood and misrepresented by the international community. But a history of indifference towards the outside world has left them without the skillset to counter-respond effectively. Losing the war of perception, Beijing is determined to seize control over the portrayal of China's image abroad. To that end, a concerted global campaign is underway to disseminate the "authorised version" of the China story. State machinery is mobilised and media outlets such as the China Central Television (CCTV) and Xinhua news agency are broadcasting international multilingual programmes to counteract perceived distorted reporting and disinformation on China.

The impact of these heavily financed, state-engineered soft power campaigns is still too early to assess. But one thing is certain, this is a historic turnaround for an ancient civilisation renowned for its benign disregard of others' view of itself. Leaders of modern China are fast realising that in today's interconnected reality, international opinions matter, and these can adversely affect China's national as well as international interests. Beijing cannot afford to ignore them and must become engaged in this battle of perception.

As in the past, the present batch of Western-educated Chinese have a critical role in narrowing the perception gap. Some, like Zhang Weiwei of Fudan University, for instance, have returned home to speak on behalf of the state, articulating the China model to the world. Others, such as Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution, have chosen to remain in the West. And like their forebears, this new generation of overseas Chinese are cultural emissaries in varied ways. But recent developments, China's rise in particular, have brought into sharper focus certain distinct features of the overseas Chinese experience and status.

China, overseas Chinese and the world

In some parts of Southeast Asia, the PRC's growing presence has roused anew the age-old suspicions over the local Chinese's political allegiance. The current intensifying Sino-US rivalry has similarly cast a cloud over the Chinese Americans' sense of loyalty. Such apprehensions are expected to persist. But from China's perspective, there is no ambiguity regarding the citizenship of overseas Chinese. During the 1955 Bandung Conference, Premier Zhou Enlai made it clear that Chinese who have chosen foreign nationality are no longer subjects of the PRC, and must be loyal to their new country.

...the overseas Chinese are morphing into a distinct cultural force of their own, albeit one with Chinese roots, but imbued with a unique cosmopolitan personality. Even with these diversifications, these Chinese remain a vital conduit linking China to the outside world.

Though no longer tied to the PRC "nation-state", the ties of the overseas Chinese to China in terms of its "civilisation" are less straightforward. As a country, China has been touted as being founded on historical and cultural unity. Some of the Chinese immigrants, like those in Malaysia, continue to preserve the traditional Chinese ways of life, thus retaining a strong affinity with and remaining a part of the Sinic civilisation.

The existence of these enclaves shows that the Chinese civilisation has not merely expanded beyond the mainland but is no longer confined by the modern national state borders. In other words, the PRC is no longer the sole custodian and bearer of the Han culture. The overseas Chinese communities in other nation states are another source and representation of the Sinic civilisation.

To be sure, the Chinese overseas are not a homogeneous grouping. Not all have preserved their native heritage to the same degree as those in Malaysia. Most have actually evolved into heterogeneous communities, embracing multiculturalism, becoming multilingual and practising multiple religions.

These changes suggest that the Sinic civilisation is evolving into a bigger civilisational family with multicultural, multireligious Chinese kindred. In fact, the overseas Chinese are morphing into a distinct cultural force of their own, albeit one with Chinese roots, but imbued with a unique cosmopolitan personality. Even with these diversifications, these Chinese remain a vital conduit linking China to the outside world. Over time, they have acquired an acculturated Chinese voice, which is neither native nor foreign, that finds resonance across a broad cultural spectrum.

These cross-cultural fusions equipped Wang, a lauded Confucian scholarly gentleman, junzi, with a unique set of critical inter-civilisational acumen.

We see the manifestation of these metamorphoses in Wang Gungwu. Currently based in Singapore, Wang's affinity to China today is more cultural than political. As a Southeast Asian, his "Chinese-ness" was moulded in a milieu of ethno-linguistic diversity and assorted spiritualities. These cross-cultural fusions equipped Wang, a lauded Confucian scholarly gentleman, junzi, with a unique set of critical inter-civilisational acumen. Wang's command of the English language and lucid style of writing, for example, made his scholarship directly accessible to the global community.

As the PRC takes centre stage in the world, Beijing is intent on gaining an upper hand in shaping the China narrative. The Chinese state initiatives have brought to the surface the overseas Chinese own diverging yet critical role in explaining the China phenomenon. Scholars like Wang have actually transformed into transnational, multicultural intermediaries - setting themselves apart as independent emissaries straddling East and West, with a distinctive hyphenated Chinese voice, to narrate the China story to the rest.

In a pioneering class of bridge-building junzi, Wang's illustrious academic career was part of the scholastic vanguard that introduced an insular Sinic civilisation to the wider world. This is important not least because the rise of China is the story of our times. And crucially, this is a fast developing, unfolding story that is propelling the 21st century into a critical moment in history.

Indeed, China rising is triggering a tectonic reconfiguration of the existing US-led world order. As in any great power transitions, the risk of tripping into the Thucydides Trap is ever present. But today's risk is aggravated by the fact that the Sino-US matchup is an encounter between two fundamentally different civilisational powers. It is a rivalry that is becoming increasingly hostile, marred by deep mistrust and misperceptions.

Herein lies the pivotal significance of Wang's life and work, namely, to help mitigate the trust and perception deficits between the Chinese and the American world, and to lay the cross-cultural groundwork needed to turn around the current all-or-nothing showdown between these two great civilisational powers into one of peaceful coexistence.

This is an edited version of the book chapter "A Pioneering Class of Bridge-Building Junzi" from the book Wang Gungwu and Malaysia (2021) published by the University of Malaya Press.

Related: Wang Gungwu: Sinology belongs to the world | Wang Gungwu: The high road to pluralist sinology | Professor Wang Gungwu's Tang Prize 2021 lecture: China's road from wen to shi | Wang Gungwu: When "home" and "country" are not the same | The Shanghai middle class: Embracing 'cosmopolitanism with Chinese characteristics'? | Remembering Yü Ying-shih in Singapore: An ambitious social experiment disrupted