A tribute to Professor Yü Ying-shih: Remembering the lessons my teacher taught me

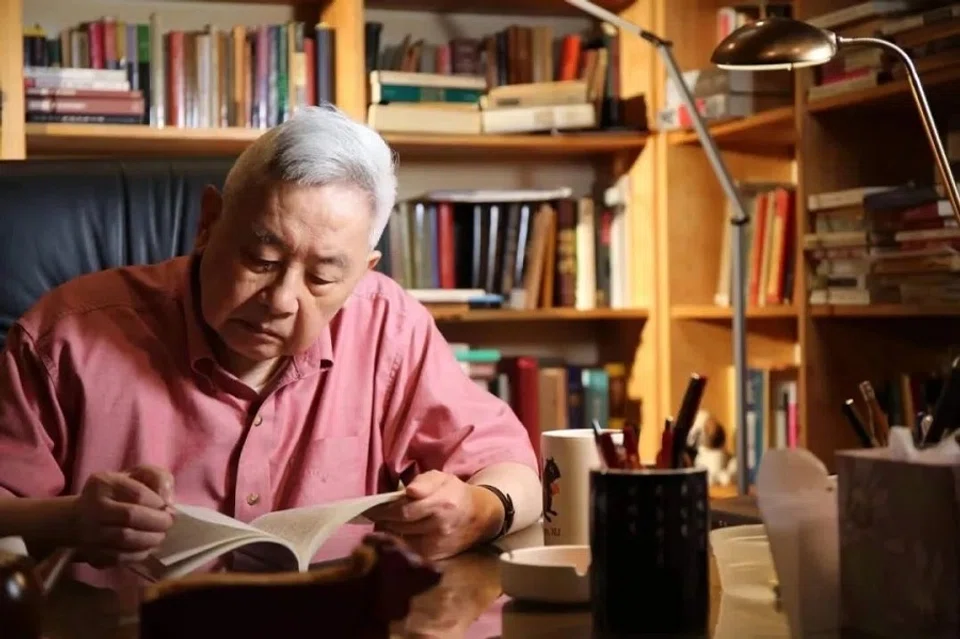

Renowned American historian and sinologist Yü Ying-shih passed away on 1 August 2021 aged 91. ThinkChina reproduces this essay which cultural historian Cheng Pei-kai wrote last year to commemorate Professor Yü's 90th birthday. As Cheng's teacher of over 40 years, one of the greatest lessons Professor Yü had taught Cheng was to be a historian with a heart and a sense of sympathy. One must learn to listen to the wind, rain, laughter and crying in human history.

My teacher Professor Yü Ying-shih turns 90 this year. As his student, it is a matter of course that I should write a congratulatory piece in appreciation of how he has been guiding me patiently and sincerely over several decades. Yes, Professor Yü has been teaching and supporting me unceasingly, with full devotion, for 42 years now. That's more than the number of years at which Confucius supposedly became "free from doubts". I cannot help but feel very much put to shame. It's like my teacher's kindness has been wasted on me, for only at the age of 70 did I finally come to apprehend the true way of academic inquiry, and begin to appreciate how I might explore "freedom from doubts".

When the Professor received the first Tang Prize in Sinology in 2014, the awarding speech included a quote from the Grand Historian Sima Qian - about "probing into the junction of Heaven and Man, comprehending the changes from ancient times to the present day" - in commendation of his scholarly achievements. My teacher was hailed in the speech as the best in contemporary Sinological studies, and he deserved to be called so. The Tang Prize was given out in Taiwan based on the opinions of international Sinologists collected by the Academia Sinica. Although it might not be well-known in mainland China and the West, it did represent the unanimous approval of academia.

Earlier in 2006, the Professor received the John W. Kluge Prize for the Study of Humanity, a distinguished accolade awarded by the US Library of Congress biennially. This conferment represented the common recognition in Western intellectual circles of the Professor's contributions to the academic study of the humanities. It was a reflection of the high esteem held by the international community of humanities scholars for Professor Yü's academic accomplishments. Above all, it indicated that Professor Yü's works had given a direction to Western intellectual explorations in humanistic matters, enabling the West to gradually better understand the paths for breakthroughs in thinking as afforded by Chinese cultural traditions for human civilisation. My teacher has thus been a relevant inspiration in view of the general predicament that the cultures of the world are sliding into collectively.

My apprehension of the way of academic inquiry

In the chapter "The Master Seldom Spoke" in the Analects, there are the following words of admiration from Yan Hui for his teacher Confucius: "The more I look up at [what our Master embodies], the higher It rises. The more I delve into It, the more impenetrable It becomes. I catch a glimpse of It in front, and It is instantly behind me. Nevertheless, our Master is good at luring people on methodically. He has broadened me with culture, restrained me with proprieties. Even if I wished to stop, I could not. When at times I have exhausted all my capabilities, something seems to stand loftily before me. Even though I desire to follow It, I can find no route to It."

I'm ashamed for not attaining to Yan Hui's level, but I'm also glad that I'm not as short-lived as he was. Having managed to spend many years in academic inquiry, I'm fortunate to be still around, still grateful to my teacher beyond the age of 70. Even so, after much musing, Yan Hui's remark continues to seem particularly appropriate.

The Han dynasty commentator Kong Anguo's explication of the passage cited above puts it quite clearly: "Yan speaks of being broadened with culture by the Master, and yet also restrained with proprieties, so that he could not stop even if he wanted to, and as a result, he has exhausted his own capabilities. Something stands before him, and yet it is lofty and unreachable. In other words, even though he has been skilfully enticed by the Master, he is still unable to attain to where the Master stands."

In reality, Yan Hui's remark is telling us four things, which I can connect to a corresponding fourfold sense I get from following Professor Yü in the path of scholarship.

Firstly, my teacher's learning is incomparably deep. The more I learn, the more I perceive that ours is an undertaking that knows no bounds.

Secondly, my teacher's learning is all-encompassing. It spans over ages and different cultures. It goes from trade and expansion in Han China to Ming and Qing thought; from Fang Yizhi to Zhang Xuecheng and to Chen Yinke; from Western democracy and liberty to The Dream of the Red Chamber, and then to Hu Shih, Gu Jiegang and Ch'ien Mu; from the scholar gentry of old to the pursuits of the modern intelligentsia; from Bergson to Weber and to Young and Old Marx; from the social functions of the Three Traditions (Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism) to Zhu Xi's historical world; from the political predicament of the modern Chinese to transcendence beyond confusion (as practised in high antiquity with a grasp of "the junction between Heaven and Man"). My teacher's learning is dazzling in its range - as "I catch a glimpse of It in front ... It is instantly behind me" indeed.

Thirdly, my teacher emphasises broadening by means of culture, as well as restraint by means of proprieties. He has taught me not only how to conduct academic inquiry, but also how to live as a proper human being - to break through the confines of my untamed and ignorant mind, discover the true convictions I would stand for unwaveringly, and take constructive academic and cultural work as the calling of a lifetime.

Fourthly, in his academic endeavours, my teacher contemplates the contemporary situation of Chinese culture, works tirelessly, practices what he preaches. As he does so, we, his students, are left astounded, looking on and knowing that his level is way beyond our reach.

Retirement as the time for writing books

When I retired from the City University of Hong Kong (CityU) a number of years ago, Professor Yü gifted me with a poem in the form of a piece of calligraphy, in which he continued to show great expectations for me.

The poem reads: "For thirty years, your sentiments and thoughts have been tied to the Way and the arts / You were active in lecturing at a podium, and in stillness, you would compose poetry / Now, at Wu Kai Sha, with the mountains and sea in the distant view / The days in withdrawal are just the right time for writing books".

There was an explicit instruction attached to the end of the poem. It stated: "Pei-kai has retired, but he has not stopped working. To live in Wu Kai Sha, take in the view of the mountains and the sea, and focus on writing - that is life at its best."

Wu Kai Sha, incidentally, is in the northeastern parts of the New Territories. It is one of the more remote suburban areas of the SAR, such that even many Hong Kongers don't know where it is. I chose to live here to distance myself from the clamours of the mundane, so that I might immerse myself in the spiritual world of my pursuit. Somehow, Professor Yü seemed to be very familiar with Wu Kai Sha's physical environment. Out of curiosity, I asked him why.

According to him, in the early 1970s, he had left his teaching post at Harvard temporarily, and served as the President of the New Asia College and the Pro-Vice Chancellor of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

Relative to where he was working, Wu Kai Sha was reachable by boat, just on the opposite side of a bay and beyond the waters of Tolo Harbour. Back in those days, it was something of a pleasantly wild area, where one could only find the YMCA's camp and the original residents of the old Wu Kai Sha village. Sometimes he would take students across the bay to participate in certain activities at Wu Kai Sha, such as orientation training for new students. My retirement residence was located precisely where he used to sing songs around a campfire with his Hong Kong students.

Those were the days when there were struggles over CUHK's reconstitution, the troubles of a massive uproar, informed by conflict between colonial political realities and one's ideals and aspirations, so the memories from that time were not very happy ones. Nevertheless, Professor Yü could still remember Wu Kai Sha's shimmering waters and lush woods, its remoteness from mundane clamour, the whole rustic feel of the locality. He knew it as a good place for retirement and the writing of books.

I suppose my teacher's instruction was linked to his own experience. To say that I could focus on writing in my retirement was a reflection of what he himself did. He made the choice to spend his retirement quietly in the suburbs of Princeton, nestled in the greenery of the woods, where he would continue to let the profound brilliance of his thoughts shine through. There he has been, still explicating the vastness, depth, obscurity, precariousness and subtleties in Chinese culture as a historical tradition with his combination of Chinese and Western academic prowess, producing works like Zhu Xi's Historical World and Between Heaven and Man.

The poem written by my teacher also brought to mind how I made an important choice in my life. Back in 1998, I left America, where I had lived for almost 30 years, and went to CityU to establish a Chinese Civilisation Centre for it. For this new enterprise, I cast aside the traditional curriculum that revolved around cramming and rote learning, and pushed for a more diversified form of teaching. A very significant factor behind my decision to do all this was the influence and encouragement from Professor Yü.

When I was studying at Yale University, I was taught by Professor Jonathan D. Spence and Professor Yü, from whom I gained a whole new outlook on how Chinese history and culture were to be understood and taught. I learnt that one has to combine both the macroscopic and the microscopic perspective, to examine minutiae from the viewpoint of greater things and see the big picture in the finer details, to contemplate the human condition repeatedly, to present the relationship between cultural traditions and concrete personal experiences.

History education has very specific social functions. It can help to form cultural consensus, and be closely relevant to everyone's life experiences and choices. To have young people study history and culture, nurture a humanistic spirit, develop the ability for independent thinking, and adequately bring to fruition the meaning of their own lives is the foremost task for the teaching of history.

...the need to enhance humanities education was currently a common problem throughout the world. The way ahead for Chinese culture was to turn the teaching of the subject into an avenue for nurturing independent personality in young people.

Thus, when Chang Hsin-kang, the President of CityU, invited me to Hong Kong, I was tempted. Here was a commercial society bent on pursuing quick, tangible results. He was asking me to come to a polytechnic university defined by an extreme emphasis on practicality, and set up Chinese culture as a subject of study. Mine was to be a 6-credit required course, which would account for 7% of the credit units to be earned by every undergraduate within their three years at the university.

One of the special reasons I found the offer tempting was that I personally had a sentimental attachment to China. I had always hoped to give back to Chinese society. I hoped that the young people of postcolonial Hong Kong would learn about the relationship between themselves and their cultural traditions, come to a clear history-based understanding of their own identity, and thereby make life choices that would be more thoroughly thought through, or at least alleviate the psychological anxieties that came with the handover of Hong Kong to China.

At that time, I already had two decades of teaching experience in the US, and was used to living a stable and comfortable life where I was. To me, Hong Kong was a foreign land where I had never resided in. I was somewhat hesitant about giving up in my fifties the American life I had long been accustomed to, and taking on the challenges of a whole new environment. As I struggled over the question of whether I should go to Hong Kong, I paid a visit to Professor Yü just to seek his advice.

The Professor knew very well that even though I had suffered under the Kuomintang government's oppression, I still wanted to do all I could for Chinese culture. So, he reminded me of how my personal circumstances had become better over the years, and encouraged me to take the plunge and open a new chapter in my career in academic education. According to him, there was a streak of obstinacy in my easy-going character, but what seemed to be rebelliousness on my part was only insistence on the good, so I was the right kind of person to initiate an undertaking that no one had ever done before. Furthermore, the need to enhance humanities education was currently a common problem throughout the world. The way ahead for Chinese culture was to turn the teaching of the subject into an avenue for nurturing independent personality in young people.

Professor Yü's encouragement spurred me into making up my mind. As a result, I came to Hong Kong, known at that time as a "cultural desert", and worked hard to build an oasis, so to speak, that could develop in the long run, not only on campus but also across society in general. In doing so, I hoped to fulfil my teacher's own aspirations in some way.

Interesting debates with my teacher

Many of Professor's disciples who studied with me in my younger days are impressive academic achievers. As students, they were able to follow our teacher's instructions and abide by the norms. I alone was a young rebel, often voicing my disagreement with Professor Yü.

Back then, I was indignant at the Taiwanese government's White Terror policies in the 1960s. I also looked down on how the older generation chose to live with them and not rock the boat. I left the spiritual birdcage that was Taiwan, and went to free and open America, where I leaned towards the cultural subversions of the modernists and liberalist, leftist thought. I was enamoured of Young Marx's humanitarian spirit. This was very much at variance with my teacher's conservative brand of liberalist thinking at every point from theory to social praxis.

For this reason, the two of us were always debating as we delved into academic matters, touching on everything from the Ming dynasty's intellectual and social transitions to the philosophical differences between Marx, Weber and Bergson.

What went on was somewhat at odds with the Chinese traditional norms of treating one's teacher with respect, so every argument would leave me feeling apologetic.

As I look back, it was very interesting for me to debate with Professor Yü. That he could tolerate my constant questioning and talking back was something quite extraordinary. What went on was somewhat at odds with the Chinese traditional norms of treating one's teacher with respect, so every argument would leave me feeling apologetic. I felt as if we were rehearsing a play about "I love my teacher, but I love Truth even more", over and over again. I was never quite satisfied with each performance, and so there was the need to keep doing it.

As Hu Shih once said, "Tolerance is more important than freedom." Could it be that my teacher was tolerating my leftist thinking in the hope that I would see in our arguments how egoistically insistent I was on being right? I do not know. Maybe that was why he kept reminding me of one thing: that while there could be different directions for humanitarian ideals, it was the concrete unfolding of social praxis in history that was the fundamentals that we must not lose sight of as historians.

Our debates would go from the social changes brought about by Wang Anshi's and Zhang Juzheng's reforms, to the conflicts between ideals and realities, and then turn to the ideas and policies of America's Democrats and Republicans. Even though we could never come to any conclusion based on empirical reasoning, our concern for real-life affairs was kept alive, never weakened.

No matter how we argued, at the end of the day, there would always be a sumptuous meal (sometimes complete with a painstakingly made "eight treasures duck") prepared by Mrs Yü (Shu-ping), before which the teacher and the student would agree to a truce and join each other in enjoying good food.

Although our ultimate concerns on the intellectual level were for the future of humanity, the issues closest to our hearts were still those of the divergent pathways that lay before China.

My early understanding of history was drawn towards macroscopic trends. From the theoretical constructs of intellectual and political institutional history, my gaze gradually turned towards the influences of socioeconomic entities on cultural developments. I neglected the existential, experiential aspect of personal lives in the course of history. Unknowingly, I had often fallen into the traps of traditional thinking, hung up on the abstract ideals of taking on the troubles of the nation before its people were conscious of them (as held by the 11th-century statesman Fan Zhongyan). I believed in the idea of "sacrificing the lesser self for the sake of completing the greater self". I would even quote the famous words of Sun Yat-sen ("How magnificent are the grand trends of the world! Those who flow with them flourish. Those who go against them perish.") as part of a theoretical basis for understanding the Chinese revolution and the rise of the Communist Party.

The debates between Professor Yü and myself often involved questions about the circumstances of the individual in the midst of historical movements. How should we view the currents and countercurrents of history? How might we make sense of the necessities and contingencies of history objectively? How should we make our personal choices as the crashing waves of history shape the world around us? How should we judge the historical acts of fighting against prevailing currents? Professor Yü and I were remnant people in the broad, cultural sense - Chinese intellectuals from two different generations, both forced into exile, as it were. Although our ultimate concerns on the intellectual level were for the future of humanity, the issues closest to our hearts were still those of the divergent pathways that lay before China.

There was a particular occasion when we were debating about the impact of revolution on the modernisation of China. We talked about the discrepancy between socialist ideals and actual revolutionary praxis. Our historical understanding of megatrends came into the picture.

This was what I thought: China's upheavals over the last century or so represented the realisation of objective historical developments, the clash between the agrarian cultural tradition and industrial civilisation. A common understanding emerged in this process for the sake of the survival of the Chinese nation and race, according to which China had to master the technical expertise of the foreigners to overcome them, as it were. Hence, there was an emphasis on strengthening the nation financially and militarily, a vision of establishing democracy and science à la the modern Western countries. The visionaries adopted the most poignant and radical ways of waging revolution. They raised the lofty banners of socialism and patriotism, but ended up abusing the notions of democracy and science. In striking at their own roots, they committed cultural suicide, not only sacrificing the lives of myriads of people, but also destroying their own culture and traditions.

Professor Yü basically agreed with my point of view, but only very generally. He took care to point out a blind spot in the history of the Chinese revolution: that as the revolutionaries raised a utopian ideal as their rallying call, they clouded the minds of intellectuals who could not wait to take China out of the status quo to a better place, and thereby initiated a series of radical actions that turned out to be destructive to the continuance of China's own cultural traditions.

"When we study history, we must have a historian's sense of sympathy - that is to say, sympathy for people. You analyse objective history and speak of megatrends, but you're only applying some readymade theories. You have overlooked the human beings actually living in the world, and forgotten about the tribulations they undergo..." - Professor Yü

Words like a thunderbolt

As I was debating with Professor Yü over the traceable trajectories of historical developments, a curious thought hit me. I pointed out that the course of history was never altered by personal will. It followed that the radical leanings of revolution were inevitable. They were the realisation of megatrends in China since the early modern period, the indifferent unfolding of history in all its objectivity. Might wave after wave of radicalisation in the process of China's revolution not be for actualising the possibility of a utopian ideal, achievable by conducting on Chinese soil the boldest social experiments in human history?

As I fleshed out my corollaries as per logical rationality and argued powerfully and confidently, the Professor suddenly stood up. With a solemn expression, he said, "When we study history, we must have a historian's sense of sympathy - that is to say, sympathy for people. You analyse objective history and speak of megatrends, but you're only applying some readymade theories. You have overlooked the human beings actually living in the world, and forgotten about the tribulations they undergo. The bold social experiments you speak of have made living impossible for large parts of the populace. That's suffering experienced by countless Chinese people. It is true that there have been many revolutionary social experiments in human history. While they brought about history-shaping changes, they often also threw the people into endless misery. We are Chinese. I do not want the Chinese people to go through social experiments of this sort!"

These words struck me like a thunderbolt. I was stunned, left speechless all of a sudden. My teacher was right. As I studied history, I was indeed going by readymade theories. Theory came first for me. In finding support for socialism from a philosophical angle, I embraced the fair distribution of social resources, and even recognised the historical significance of social revolutions as something positive. Having gained knowledge of various theories of history, I imagined that the key was to rationally analyse what people did in the past. This was supposed to be a professional discipline built on documentation and data. One was supposed to keep the emotional stance of personal subjectivity out of it as far as possible. And yet, even as I delved into socialism industriously, analysing the legal principles that might legitimise the revolutionary toppling of class oppression and exploitation, could it be that I was just indulging in theoretical self-consolation in an ivory tower, and had never truly considered how living, breathing people in history dealt with the massive tsunami of revolution? Had I ever seriously put myself in their shoes? Had I ever empathised with them for all their sufferings?

Put a listening ear to the monumental achievements in human history, and you will hear the wind, the rain, laughter and crying.

This particular round of debate had a huge impact on me. From there on, I ceased to argue with Professor Yü. In addition, the attitude with which I would study history was completely changed. I began to pay attention to the specific life experiences of historical figures. History would no longer be cold, hard, objective data. It is filled with the warmth and tragedies of life experiences. There is happiness, pain, joy and sadness here, just as the lives we live ourselves are embedded with a mix of feelings, even the sorrows of separation and death.

Put a listening ear to the monumental achievements in human history, and you will hear the wind, the rain, laughter and crying. You will hear the battle cries of heroes, the sobbing of widows in the barren wilderness, the soulful tolls of a monastery's bell that wafted at midnight to a traveller in a boat, the desert sands lamenting about the hardships of exile. Human history comes with flesh and blood. It has emotions and souls running through it, just as we ourselves are creatures of flesh and blood, each complete with emotions and a soul. The study and teaching of history cannot possibly be done the way we do the natural sciences. We cannot only go by empirical reasoning and only believe in instrumental rationality, excluding our idealistic yearnings and emotional attachments.

Professor Yü's five virtues

I started out as an arrogant, domineering leftist youth, but became a more meek-mannered and collected culturatus over time. The shift in my character was undoubtedly rooted in my personal experiences and choices, but it also came about due to a very great extent to Professor Yü's encouragements.

As I recall, on one occasion over 30 years ago when the two of us were debating, I was underscoring my anti-traditional, rebellious inclinations. I wanted to take up the anti-traditional spirit of the May Fourth Movement, and denounce the conservative, closed ideology of the Confucians. Surprisingly, my teacher listened to my spirited prattle quietly for a while, and then slowly remarked, "As far as I can tell from your character, I think you are actually a Confucian." What he said left me dumbfounded. I really did not know what he was saying. I thought the Professor was only speaking ironically, trying to cool me down and pull me from emotional excitement back to rational discourse.

Fast forward to seven or eight years ago, I was visiting my teacher at Princeton with my wife. In order to reward this old student for coming with a loved one, Mrs Yü took the effort to prepare a "crispy aromatic duck" and a soy sauce chicken for the welcoming meal. She talked about how she had made her "eight treasures duck" on many occasions for me, and also how Professor Yü and I used to debate with each other frequently. My wife remarked jestingly on what an outrageous person that disputatious student - me - was, given that he was unyielding in his position with the hardness of a duck's bill, so to speak, even though he had eaten the ducks so painstakingly prepared on his opponent's side. "What a wild and intractable fellow," she said.

Getting a bit curious, she went on to ask Professor Yü, "Why would you spend so much time and effort to debate with this indelicate student anyway?" Seated on a sofa, the Professor laughed heartily. He put his hands apart, and replied, "I just knew at that time that he would surely change his mind at some point, and become as he is today - benign, honest, respectful, temperate and deferential." With that, he continued to laugh heartily, apparently quite pleased with himself - so much so that Mrs Yü and my wife also laughed with him. I could only coyly join them.

Truth be told, I was awash with mixed feelings. Especially when I heard that I had supposedly turned from a leftist student with radical thinking to someone who was "benign, honest, respectful, temperate and deferential". I thought: Shouldn't these words apply to Professor Yü instead?

In fact, he was a gentleman with these five virtues and yet also marked by modernity. His was a moral being that had been developed through thorough insight into history and cultural traditions, as well as self-cultivation in the midst of living and dealing with people. Mrs Yü often say that her husband is incisive and pointed in his thinking, that he too gets mad at matters he cannot agree with, even to the point of blurting out vitriolic curses - but he would always act modestly and affably towards others nonetheless. Indeed, the Professor himself once told me that he had a certain latent knack. Supposedly, when people or things incurred his extreme displeasure, he was capable of immediately delivering a vicious attack, yet he would always be unwilling to do so. He was always thinking about giving others some leeway.

It thus occurs to me that what the Confucians call "benignity", "honesty", "respectfulness", "temperateness" and "deference" are really just the outward, behavioural manifestation of virtuousness. What lies beneath these qualities is a deep and hidden spiritual underpinning. When the Confucians expound on "rectifying one's heart", "seeking to be sincere in one's thoughts", "personal cultivation", "regulating one's family", "extending one's knowledge to the utmost", "the investigation of things", "maintaining carefulness in privacy", "innate knowledge of the good", "unity of knowledge and action", there is universal significance in all such notions for human ethics.

As a modern intellectual who advocates democracy, liberty and independent thinking, Professor Yü has internalised what is good in Chinese cultural traditions. He demonstrates the humanistic spirit of the Confucians in a manner that transcends national or ethnic consciousness, and yet he has never claimed to be a bearer of the Confucian or New Confucian legacy. That's being "benign, honest, respectful, temperate and deferential" in the true sense, nothing short of admirable.

Kindness unforgotten in life and in death

As I recall, Professor Yü has taken meticulous care of me. He has never made any mention of the labour he put in for this. He makes me feel as if I have been basking in boundless, life-giving sunlight. What he gives far exceeds any form of repayment I can imagine on my part. No wonder the ancients told intriguing stories about making efforts to repay one's benefactor: Jade annuli were gifted, and grass was woven together to trip an enemy (结草衔环), all in reciprocation for kindness unforgotten in life and in death.

In the early 1970s, I was blacklisted by the Kuomintang government for being a leftist who took part in the Protect the Diaoyu Islands movement in North America. My passport was revoked, such that I could not return to Taiwan for two decades. After martial law was lifted in Taiwan, Professor Yü told me one day that I should be able to see my parents back home since I had only been teaching in university all these years and not gotten myself involved in any political activities. He said he was very close to the consul general in New York, and would ask around for me. In order to help me obtain my passport and visa to go back to Taiwan, he went through a few rounds of communication with the consulate-general in New York. As a result, I was eventually able to go home after two decades of being abroad, and got to see my parents, whom I missed so much.

Even though I shall be forever grateful for what Professor Yü did, he has never mentioned it. He probably simply thought it was a joy to help others. While he did good without expecting repayment, he was being a great benefactor to me. Through all my days, I shall never forget the remarkable kindness he extended to me in this matter.

I believe Professor Yü will approve of my understanding of the meaning of history and culture, as well as my way of teaching history as described above.

When teaching Chinese history and culture in Hong Kong, I had often presented Chinese culture to my students as a great tradition that is vast and deep, an incredibly long river with distant sources. It necessarily contains both the good and the bad, precisely because of its vastness, such that it is both a tapestry of glorious acts and a cesspool of sordidness. And because this river is incredibly long, we see many touching stories of loyalty and righteousness in it, as well as an abundance of evil, treacherous scheming. Such a phenomenon is not restricted to Chinese history. It is present in Western history too. Just as we have Confucius, Mencius, Laozi and Zhuangzi, there are people like Socrates, Plato, Siddhartha Gautama and Jesus Christ elsewhere. Just as we have the tyrannical first emperor Qin Shihuang, they have Emperor Nero. Just as we have the literary genius of Li Bai, Du Fu, Su Shi and Tang Xianzu, they have Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe.

We study history and culture because we hope to draw from them, cultural resources that are wholesome, beautiful and good, and let history teach us to abandon all that is abominable, so that we may live as people with a good moral sense. But, of course, we have no unrealistic fantasies. We do not expect everyone to become a sage or a saint. We only hope that our young people will adequately fulfil their self-development, understand the lessons taught by history, always think twice before they act, and never do harm to others just for selfish gains. I believe Professor Yü will approve of my understanding of the meaning of history and culture, as well as my way of teaching history as described above.

That Professor Yü's learning is immense and wonderfully connective is a historical fact, about which I need not say more here. As his student of over 40 years, I enjoy his warm, vernal influence. I am deeply aware that my teacher has done so much for me that no comparable repayment is possible on my part. I can only offer a humble gift here, and pen this essay as a form of well wishes for my teacher in his 90th year.

Note:

An earlier version of this essay was included in the celebratory anthology of essays published by Taiwan's Linking Publishing to commemorate Professor Yü Ying-shih's 90th birthday. The current text is the finalised version that has been revised on invitation from Ming Pao Monthly and expanded by some 1,000 Chinese characters.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)