Must one read Chinese to appreciate Chinese calligraphy?

Teo Han Wue has always believed that one need not be literate in the Chinese language to appreciate calligraphy. He was heartened that many others seem to share his view, going by how well-received a photograph of Singaporean poet-calligrapher Pan Shou's calligraphy was at his solo photography exhibition recently. Without him regaling them with tales of Pan Shou, they found their own delight appreciating this artform through an image of an image.

I have always thought that Chinese calligraphy was too esoteric and thus could be inaccessible to people who would otherwise readily appreciate visual art forms such as painting and sculpture.

Nonetheless, as an art writer, I have maintained that the art of calligraphy need not be exclusively enjoyed by those literate in the Chinese language. The art form, characterised by the beauty of its line and expressive gestures, should appeal to everybody's sense of aesthetics regardless of textual meaning and "illegibility" especially when written in a free cursive style.

I was truly delighted when my view was somewhat affirmed by the response to an image from my solo photography exhibition "Available Light" held at Art Agenda Gallery from December 2021 to January 2022.

Never had I expected this black-and-white print entitled Pan Shou's Calligraphy to be the most popular photograph in the entire exhibition featuring 48 pictures. Many viewers were immediately drawn to it. Not only did it become the first of my work in all editions of three to be acquired by collectors within the first week, it continued to get keen attention from visitors all through the duration of the exhibition.

A paean to Pan Shou

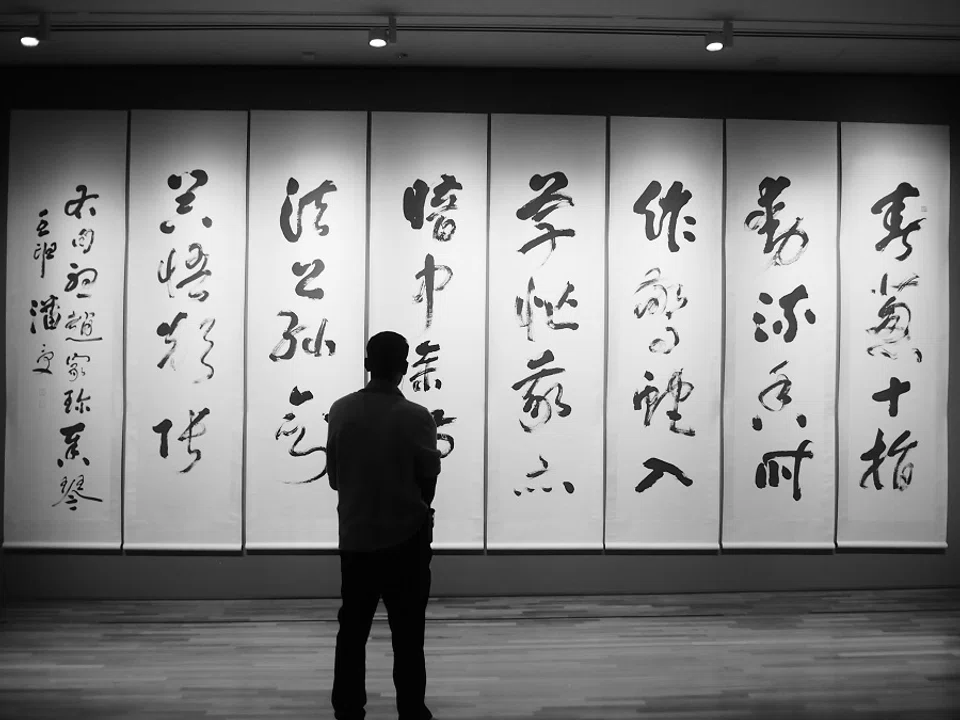

On a visit to the National Gallery Singapore in 2016, I had taken photographs of the interior of the building and of the exhibitions there. When I came to the section where works of Chinese ink art were displayed, I was as usual irresistibly drawn to a huge eight-panel scroll on the side of a narrow corridor which opens up to a much bigger exhibition space. The imposing scroll was unmistakably a work by Pan Shou, Singapore's foremost poet-calligrapher, and it took up a considerable expanse of the whole wall.

While admiring and trying to photograph it, I saw an Indian man coming into the view of my camera from my left. He was wearing an audio guide and looking at the same work with its large cursive characters in black ink on rice paper.

I suddenly realised it would make a better picture if I included him in the frame. He gladly obliged when I asked him to move closer to the centre and stand facing the scroll.

I later turned the picture into black and white to accentuate the effect of ink. But for a long time, I never thought much of the image. I had filed it away until July last year when I began selecting images for the above-mentioned exhibition that my friend Wang Zineng, founder of Art Agenda, proposed to do in his gallery.

As my curator, Zineng chose that picture to lead a group of images associated with my life as a critic/writer active in the Singapore art scene over the years. There were altogether five groups divided by themes such as nature, park life and habitats.

Right from the start, interest in Pan Shou's Calligraphy became evident and it also struck a chord among the more discerning viewers.

...I was struck by how the image must appear to represent a projection of my deep sense of appreciation of Pan Shou's poem written in his own calligraphy.

Singapore's leading art historian T. K. Sabapathy singled it out as an important work in the exhibition explaining, "This is because of who you are, as someone known for work in art discourses paying tribute to Pan Shou's calligraphy in the form of a photograph." Mr Choy Weng Yang, former curator of the National Museum Art Gallery, also picked the same picture and made a similar observation.

Then I was struck by how the image must appear to represent a projection of my deep sense of appreciation of Pan Shou's poem written in his own calligraphy.

Especially heartening for me was the interest shown by a group of curators from the National Gallery Singapore who were considering acquiring it after viewing the exhibition. Since all its three editions had been taken and none was left, one of the buyers would have to be persuaded to give it up in the interest of the national collection.

This prompted me to dwell on the background of the photograph in my guided tour to visiting groups and I went deeper into my analysis of the image, especially about Pan Shou's work in particular, and the art of calligraphy in general.

Pan Shou is known for his xing shu and cao shu (running and cursive scripts respectively), which lends a certain expressiveness with bolder and freer brushstrokes.

Pan Shou is known for his xing shu and cao shu (running and cursive scripts respectively), which lends a certain expressiveness with bolder and freer brushstrokes. This eight-panel scroll, said to have been completed at artist Henri Chen KeZhan's residence, presents just one short poem written after he saw a Chinese musician Zhao Jiazhen perform on the guqin:

Like scallions her ten fingers move swiftly as though stirring up fragrance,

At times looking like frightened snakes darting into the bush.

Secretly I study her gestures considering how my brush should move,

Maybe much as Crazy Zhang was inspired by Gongsun's sword dance.

The sword dance reference comes from a Tang Dynasty poem by Du Fu that recalls how his contemporary Zhang Xu's cursive script improved after watching Gongsun Daniang dance. Zhang is nicknamed Crazy (颠 dian) in the poem because his boldly wild strokes were often done after he had had too much to drink. In his intoxicated state he would, as the story goes, abandon his brush and pounce on the paper to write with his hair soaked in ink as though in a frenzy. While they called that crazy about 1200 years ago, it could well be a serious piece of performance art today.

...one need not be literate in the language to enjoy Chinese calligraphy. In fact, any attempt to read it as text for its meaning might even distract one from really appreciating calligraphy as visual art.

But then the image of Pan Shou's work resonated with viewers even before I started telling them this story. They just took to it without necessarily knowing the rich literary context from ancient China as intended by the artist or the photographer. Chances are, it didn't matter - at least not enough to deny them the pleasure of the art.

As I recall how the classical narrative went down with each batch of viewers I hosted, I feel it was almost like a moment of epiphany for me especially when the question "How does one appreciate Chinese calligraphy?" would invariably surface.

Innovation in calligraphy an underappreciated virtue

My experience arising from this photograph at the exhibition reinforces my belief that one need not be literate in the language to enjoy Chinese calligraphy. In fact, any attempt to read it as text for its meaning might even distract one from really appreciating calligraphy as visual art. Of course, understanding the text will take appreciation to a totally different level.

More important than textual meaning, the lines, gestures, contrast, rhythm, flow, spatial balance in the ink strokes are what the viewer should focus on to enjoy a good piece of calligraphy.

Many examples...have met with strong disapproval of and resistance to them being categorised as artists practising calligraphy simply because they are striving to strike out a new direction in the art form.

I have been following a long-drawn debate on contemporary calligraphy in Singapore and China. While artistic innovation and experimentation is seen as a virtue, it is ironically frowned upon by defenders of calligraphic tradition as an aberration. Many examples - from the hutuzi (糊涂字) or "muddled writing" of Singapore artist Lim Tze Peng to the luanshu (乱书) or "disorderly calligraphy" of China artist Wang Dongling - have met with strong disapproval of and resistance to them being categorised as artists practising calligraphy simply because they are striving to strike out a new direction in the art form.

By the Tang Dynasty, calligraphy had become a matured, deeply entrenched and highly sophisticated art form. Crazy Zhang must have found drinking wine helpful to liberate himself from inhibitions and break free from the formidable shackles of convention.

Today, more than a millennium later, we see many artists in Singapore, China and other parts of the world, being inspired by the creative spirit of past innovators like Zhang, which opens up tremendous possibilities for this ancient art form - just so that it would not remain archaic and irrelevant in the contemporary world.

Related: How the 'tree' of Chinese writing united dialects, culture and people through the millennia | Qing dynasty 'eccentric' painter Zheng Banqiao: Art is commodity and beauty is physical | Chiang Hsun: How great a mark of rebellion it is to hold an ink brush | Beautiful or outdated? The journey of Chinese characters through the ages | Copying is a virtue in Chinese ink painting

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)