Why intellectuals failed to flourish throughout 5000 years of China's history

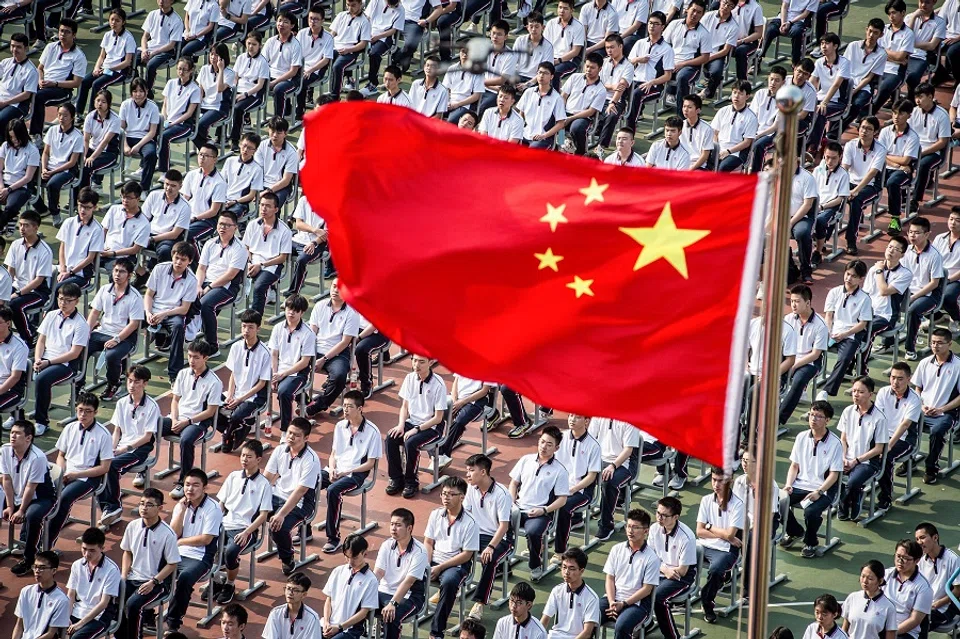

Chip Tsao laments the dearth of independent thought in China, following a long history of strictures imposed on intellectualism. If the elements of the "scholar", "intellectual" and "professional" can be combined and inculcated in the country's elites, a new dynamism can be sparked off that can help China truly modernise.

China's modernisation efforts have been unsuccessful since the Self-Strengthening Movement (1861-1895) of the Qing dynasty, which sought to incorporate Western methods in achieving reform. One of the reasons why, is that intellectuals can't seem to sprout in Chinese society. Throughout Chinese history, there were only Chinese imperial scholars.

Intellectuals are different from imperial scholars. The latter adhere closely to the current state and development of China. That said, imperial scholars during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period of Confucius and Mencius were in fact most similar to Western intellectuals in the sense that they could sit down and have a chat with the emperor. For example, Mencius had various dialogues with King Hui of Liang, while Wei Zheng expressed his doubts about national affairs openly to Emperor Taizong of Tang. Back then, ancient Chinese intellectuals possessed great autonomy over their own thoughts and ideas, even after a hierarchical structure was developed by Confucian thought, which placed the emperor above his subjects, and a father above his children.

Roots of intellectualism plucked out

Taiwanese historian Hsu Cho-yun traces the intellectual decline down to the Chenqiao Mutiny led by Zhao Kuangyin, a military general of the Later Zhou dynasty during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-979). Zhao staged a coup, thereby founding the Song dynasty. Once in power, he centralised the bureaucracy and military under his rule so that nobody would seize power the way he did again. In particular, he hosted a lavish banquet for high-ranking generals and persuaded them to resign from their positions in exchange for a life of riches in their hometowns. Following Zhao's reign, Chinese scholars were taken down a peg. They could no longer be like Russia's Leo Tolstoy or France's Voltaire, who had autonomy over their thoughts and speech outside of the political regime.

Those who could enter the Hanlin Academy (翰林院) already had most of their independent personalities castrated.

The imperial examination system also accounts for the reason why Chinese imperial scholars could not become intellectuals. Serving the country is serving the nation under the emperor's reign. One has to first take the imperial examination before doing so. The one who decides the ranking of the scholars after their scripts are vetted is the emperor himself.

Because the country is treated as a private property of the imperial family or the property of the party in a one-party state, it has never truly become a "state" in the sense of the word.

Chinese commoner scholars who wanted to become imperial scholars had to pass the imperial examination. Those who could enter the Hanlin Academy (翰林院, an elite institution for top scholars who performed secretarial and literary tasks for the court) already had most of their independent personalities castrated.

The so-called moral courage of intellectuals henceforth became a problem in Chinese society. Loyalty to the emperor comes before love of the country or state; importantly, the "state" to be loved does not refer to the modern interpretation of the word but the imperial court of emperors with the surname of Zhu or those belonging to the Aisin Gioro clan (a Manchu ruling clan). Because the country is treated as a private property of the imperial family or the property of the party in a one-party state, it has never truly become a "state" in the sense of the word. The military, for one, was never nationalised.

Taking reference from China's imperial examination, the British also established their own civil service examination in the UK. They married the merits of the Chinese system with a civil servant selection process that does not require their applicants to have independent thinking skills but only the ability to handle political affairs impartially. That is to say, the UK's internal affairs, defence, and foreign affairs ministers do not pass imperial examinations but win elections. Parliamentarians become ministers, and the Cabinet is made up of the prime minister and ministers. Officials who move up the ladder need not have independent thinking skills; only the Cabinet members of the prime minister and foreign secretary need to have them.

Today, no matter how bold critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) such as real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang and jurist Xu Zhangrun may be, they are locked in the cage of the one-party state that treats the country as the party's property.

Serving their masters or the state?

Chinese society is different. Commoner scholars produced from the imperial examination system become imperial scholars after gaining merit and fame. But they are subject to the rule of the imperial family for generations and generations - there can be no Voltaire or Tolstoy in Chinese society.

The only exception was the Beiyang era of the Republic of China (1912-1928). Because there was no monarchy and the country was divided into multiple regions, local leaders of the Beiyang government were warlords who were able to show the most respect to intellectuals. The first thing that Yan Xishan (a Chinese warlord who controlled Shanxi and strived to modernise Shanxi), Zhang Zongchang (considered one of the most brutal and ruthless Chinese warlords), and Zhang Zuolin (a Japan-backed Chinese warlord who controlled Peking) wanted to do after seizing power was to open schools. To run schools, intellectuals had to be treated as independent authorities. Thus, over the 3000 years in Chinese society following the Spring and Autumn period, the most number of "intellectuals" in the Western sense appeared during the Beiyang era. Otherwise, there could be no May Fourth Movement as well.

In those 20 glorious years, thinkers in the Republic of China were most active, and there was a harmonious blend of Chinese and Western thought. Today, no matter how bold critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) such as real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang and jurist Xu Zhangrun may be, they are locked in the cage of the one-party state that treats the country as the party's property. They can at most pretend to be Tang historian Wei Zheng or Song calligrapher Su Shi, but the "emperor" they serve will neither be Emperor Taizong of Tang (Li Shimin) nor Emperor Taizu of Song (Zhao Kuangyin).

Because they (doctors and lawyers) climbed the ladder of success formulated by the British colonial rule, and bowed down to the Legislative Council, Executive Council, Jockey Club and racehorse owners, they cannot be called true intellectuals.

As for Hong Kong and colonial education, the British guarded against intellectuals who cast doubt on the legitimacy of their governance. While they were wary of renowned Chinese thinkers such as historian Ch'ien Mu and philosopher Mou Zongsan, they respected them in private.

Lawyers and doctors who rose up in Hong Kong over the past century can only be regarded as professionals. Because they climbed the ladder of success formulated by the British colonial rule, and bowed down to the Legislative Council, Executive Council, Jockey Club and racehorse owners, they cannot be called true intellectuals. Political activist Szeto Wah, who participated in a book club in his youth, is not counted.

The tragedy of the Chinese being unable to modernise is due to the fact that the three English terms "scholars", "intellectuals" and "professionals" cannot be melded together and revolutionised. This is one area that can be further explored and focused on in the study of China.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)