History lessons: Who gets to decide what is humiliating, unfair, right or wrong?

Following a recent controversy over a history question in a national exam about whether Japan did more good than harm to China in the first half of the 20th century, Hong Kong columnist Chip Tsao asks: "Who gets to decide how history is read?"

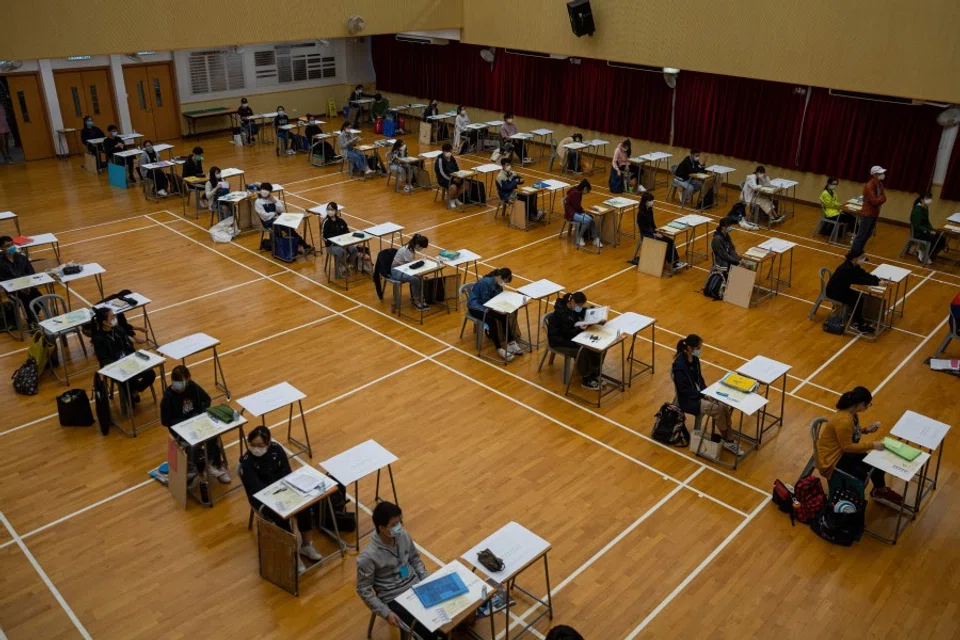

The Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority recently got into a controversy for a history question in the Diploma of Secondary Education (DSE) history paper. Students were asked whether they agreed with the statement: "Japan did more good than harm to China in the period 1900-45." Although there was no mention of the Japanese invasion, a furore over nationalism followed.

In an article on the Education Bureau website, deputy secretary for Education Hong Chan Tsui-wah wrote: "While students can be exposed to other views on the Opium Wars, such as foreign perspectives that the Opium Wars were a clash of Asian and Western cultures and that they were a result of British trade expansion, at the primary and secondary school foundation level, teachers have to make it clear to students that the treaties signed after the Opium Wars were unequal treaties. Students cannot be taught to stay detached."

... facts are different from opinions.

The Opium Wars were essentially trade wars. The product was opium, the unit of payment Manchu silver. The wars could have been prevented, but Qing dynasty official Lin Zexu, who was actively involved in the First Opium War, was not familiar with established international law and the British respect for the rule of law. There was also a lack of cultural knowledge: Lin described to the Emperor Daoguang that Western soldiers had their legs tied and could not bend at the knees (and hence could be easily defeated). And so, the Opium Wars started.

Those are the basic facts. But facts are different from opinions.

For example, "eating with chopsticks is a study in mechanics" - that is a statement of fact.

"Eating with chopsticks takes more skill than using a knife and fork" - that is a statement of opinion.

The fact that eating with chopsticks is a study in mechanics holds true whether in China or elsewhere. Nobody - Chinese, Westerner, or African - would disagree with that fundamental fact. An African would not say "eating with chopsticks is a miracle". It is not a miracle, just physics.

And people from the Yangtze River and Zhejiang region would definitely not feel it was a "humiliation", because for them, poverty is inglorious and dignity comes with wealth.

As for whether the Treaty of Nanking (which ended the First Opium War) was "unfair", that is a question of one's perspective and viewpoint.

The terms of the treaty included opening up five ports to trade. People in Beijing might see this as unfair, but for Ningbo people living in Shanghai, this led to Shanghai growing into a city thriving with trade and culture, the "Paris of the East". Even now, Shanghai is a major contributor to China's GDP. Having those five ports open also made many Ningbo businessmen rich, such as Hong Kong entertainment mogul and philanthropist Run Run Shaw and shipping tycoon Pao Yue-Kong. And people from the Yangtze River and Zhejiang region would definitely not feel it was a "humiliation", because for them, poverty is inglorious and dignity comes with wealth.

But the businessmen in Shanxi and Taiyuan would feel hard done by, having missed out on a good opportunity to link up with the world.

So, even among China's vast population, assessing the fairness of the Treaty of Nanking purely in a financial sense would yield very different viewpoints. The Qing government was forced to pay reparations of 20 million silver dollars, which was a quantitative penalty of war. And on one side of such penalties is always some form of authority. For instance, a Hong Kong judge sentenced Edward Leung to six years jail for throwing rocks in the 2016 Mong Kok civil unrest, but the knife-wielding culprit who injured three journalists was only jailed for 45 months. The judge in the latter case, Kwok Wai-kin, said the fact that the assailant was brave enough to turn himself in showed a noble spirit that was more worthy of respect than many educated people. In these two judgements, one party would be bound to feel that something was not fair.

In recent years, mainstream opinion has changed when it comes to the Opium Wars, Treaty of Nanking, and the opening of the five ports to trade; these are now said to be the start of modern China's shift towards modernisation in the material sense.

Hong Chan Tsui-wah also said, "There are already firm conclusions about some historical events, and selected materials should correctly reflect the facts of these events."

I would like to ask these officials: in 1980, the Politburo of the Communist Party of China held a meeting where paramount leader Deng Xiaoping concluded that the Cultural Revolution was a "decade of calamity". Was Deng's conclusion "firm" enough? In selecting historical materials that touch on the Cultural Revolution - if Hong Kong has the guts to do so - should it hold to Deng's "firm" conclusion that it was a "decade of calamity", or Xi Jinping's "firmer" conclusion that it was ten years of "difficult exploration"?

What is "mainstream opinion"? In recent years, mainstream opinion has changed when it comes to the Opium Wars, Treaty of Nanking, and the opening of the five ports to trade; these are now said to be the start of modern China's shift towards modernisation in the material sense (modernisation in the sense of spiritual values such as democratic freedom is another story). Besides, the ceding of Hong Kong led to it becoming the Pearl of the Orient, and it is now a major channel of China's foreign exchange. So, did the Opium Wars do "more good than harm"? From the perspective of Hong Kongers, it is definitely "all good, no bad".

What is unfair, humiliating, right and wrong... which city or province gets to decide?

But for those who crossed the border illegally from the Pearl River Delta to Hong Kong during the colonial period, after much hardship and for the farmers in northern China, struggling far away in Shanxi along the Yellow River, who had never even seen the ocean and felt that it was a humiliation to lose a single inch of land, every term of the Treaty of Nanking would be "unfair".

The only thing that should count is how much of the facts one knows, whether one thinks independently, and how one makes analyses and draws conclusions.

As Shanghainese have been saying in recent years, Shanghai's total GDP is 3.2 trillion RMB - an area that barely makes up one-thousandth of the entire country is contributing 10% of its tax revenue. Shanghainese think that is unfair, but those in Henan and Gansu would think it is very fair.

What is unfair, humiliating, right and wrong... which city or province gets to decide?

Bringing emotions into reading of history, factual discussion, and rational judgements would make some people happy while upsetting others. There would be no end to the arguments. The only thing that should count is how much of the facts one knows, whether one thinks independently, and how one makes analyses and draws conclusions. Without all that, writing "down with British colonialism" over and over on a page, or submitting a blank page with a couple of teardrop marks on it, would probably be worth nothing more than a zero on an exam.

Note:

According to a report by RTHK filed on 22 May, sources have revealed that the Examinations and Assessment Authority has decided to scrap the controversial question, and will announce details at a later date.

This article was first published in Chinese on CUP media as "读历史,扯感情,公平不公平?".

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)