SEA states have few options to mitigate escalating South China Sea tensions

Tensions in the South China Sea have surged since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. China has pressed its jurisdictional claims prompting the US to increase its criticism of Beijing's actions and its military presence in the South China Sea. In response to China's activities, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam have rejected Beijing's nine-dash line claims and invoked international law and the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling in support of their maritime sovereign rights. ISEAS academic Ian Storey takes stock of the situation and gives a broad sweep of what we can expect in the next 18 months.

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in March, tensions in the South China Sea (SCS) have surged. This is mainly the result of China's continued assertiveness coupled with the sharp deterioration in US-China relations over a variety of issues including the SCS itself.

Actions undertaken by Beijing to assert its jurisdictional claims, and demonstrate that the coronavirus has not undermined its political resolve or the operational readiness of the People's Liberation Army (PLA), have been counterproductive. The US has stepped up its military presence in the SCS as well as its criticism of China's actions. Most importantly, in support of the Southeast Asian claimants, Washington has aligned its SCS policy with the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling. China and the US accuse each other of provoking tensions and militarising the dispute.

While the maritime states of Southeast Asia are generally supportive of America's support for their maritime rights in their exclusive economic zones (EEZ), they have refrained from publicly saying so to avoid incurring Beijing's anger.

The Southeast Asian claimants believe that Beijing has taken advantage of the pandemic to advance its claims and have responded by hardening their positions. They continue to reject the legal basis of China's nine-dash line and have resurrected the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling. While the maritime states of Southeast Asia are generally supportive of America's support for their maritime rights in their exclusive economic zones (EEZ), they have refrained from publicly saying so to avoid incurring Beijing's anger.

Over the next 18 months, a let-up in tensions is unlikely. US-China relations will worsen irrespective of which candidate wins the November presidential election. China and the US will increase their military activities in the SCS, raising the risk of a confrontation. Rising tensions in the Taiwan Strait will have a spill-over effect on the SCS dispute. Southeast Asian attempts to protect their sovereign rights by emphasising the importance of international law and through negotiations with China for a Code of Conduct (CoC) for the SCS will do little to change the central dynamics of the dispute.

The Chinese government has denied that it has taken advantage of Covid-19 to push its claims.

Actions, reactions and lawfare

China asserts its claims

China's policy goals in the SCS in 2020 have remained unchanged: to press its territorial and jurisdictional claims and undermine those of the Southeast Asian claimants. In pursuit of those goals, Beijing continues to employ the PLA-Navy, China Coast Guard (CCG) and maritime militia. During the pandemic, China has stepped up its activities in the SCS to show audiences at home and abroad that its political will and military/paramilitary capabilities are unaffected. The Chinese government has denied that it has taken advantage of Covid-19 to push its claims.

To underscore its claims to resources within the nine-dash line, China surged fishing boats into the waters adjacent to Indonesia's Natuna Islands in December 2019 and early 2020, deployed survey vessels into the EEZs of Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines, reiterated its claims at the UN while rejecting those of the Southeast Asian claimants, harassed - and on one occasion sank - Southeast Asian fishing boats, and imposed its annual unilateral fishing ban in northern parts of the SCS between 1 May and 16 August. In April, Beijing announced the creation of two new administrative districts to cover the Paracels and Spratlys and named 80 geographical features. The PLA has increased the tempo of naval exercises in the SCS and deployed maritime patrol aircraft to its artificial islands in the Spratlys. In late August, in a major show of force aimed at the US, the PLA launched four medium-range anti-ship ballistic missiles - sometimes dubbed "aircraft carrier killers" - from mainland China into the SCS.

US responses

In response, the US has increased its military activities in the SCS, heavily criticised China's actions and aligned its policy with the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling which declared Beijing's "historic rights" incompatible with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Specifically, the US rejected as unlawful China's nine-dash line, its claims to offshore resources in the EEZs of Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia, and its territorial claims to Mischief Reef, Second Thomas Shoal and James Shoal.

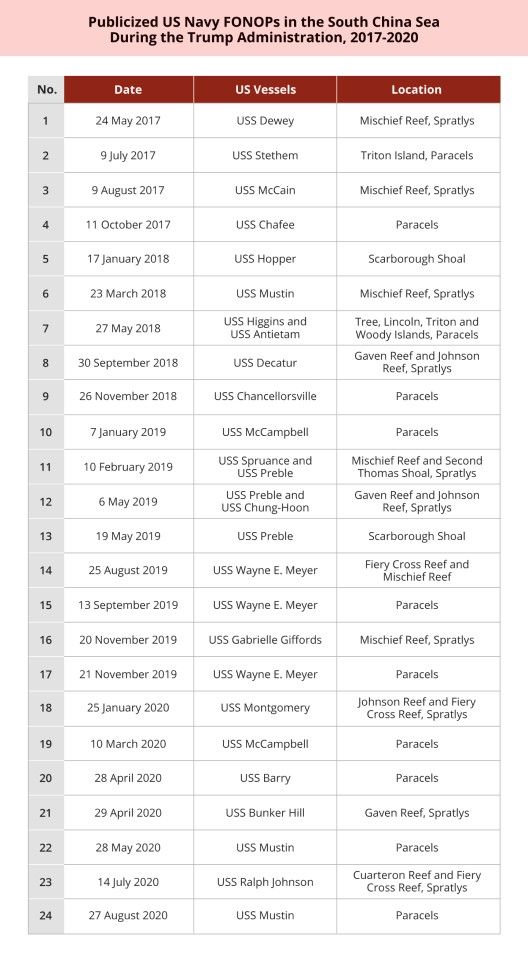

The Pentagon has increased the frequency of Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the SCS. In the first seven months of 2020, the US Navy conducted seven FONOPs in the Paracels and Spratlys, compared to eight in 2019, five in 2018 and four in 2017 (see Table 1). The US Navy has also conducted a series of high-profile exercises in the SCS - including dual aircraft carrier operations for the first time since 2014 - and increased submarine deployments and maritime air patrols. In April and May, US Navy warships shadowed a Chinese survey ship in Malaysia's EEZ. The US Air Force has stepped up B-52, B1-B and B-2 strategic bomber missions over the SCS.

The Trump administration has accused China of taking advantage of the pandemic to push its claims and in April called on Beijing to cease its "provocative actions" and "bullying behaviour". More significantly, the US has taken a more explicit stand on the legal basis of China's claims. On 1 June, the US submitted a letter to the UN which rejected China's maritime claims in the SCS as being inconsistent with UNCLOS. On 13 July, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo issued a major statement which endorsed the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling. Specifically, the US rejected as unlawful China's nine-dash line, its claims to offshore resources in the EEZs of Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia, and its territorial claims to Mischief Reef, Second Thomas Shoal and James Shoal. Pompeo stated that "the world will not allow Beijing to treat the South China Sea as its maritime empire. America stands with our Southeast Asian allies and partners in protecting their sovereign rights to offshore resources, consistent with their rights and obligations under international law."

In a speech to a think tank in Washington D.C. the day after Pompeo's statement, US assistant secretary of state for East Asia and the Pacific, David Stilwell, described Chinese corporations that undertake work in the SCS as "tools of economic coercion and international abuse", that in the CoC talks China was trying to restrict the ASEAN states' ability to conduct military exercises with foreign countries and was employing "gangster tactics" to prevent the Southeast Asian claimants from entering into energy agreements with non-Chinese corporations. Stilwell also raised the possibility that Washington would impose sanctions on individuals or corporations involved in implementing Beijing's policy in the SCS. On 26 August the US State Department imposed sanctions on an undisclosed number of Chinese citizens "responsible for, or complicit in, either the large-scale reclamation, construction, or militarisation of disputed outposts in the South China Sea" while the US Department of Commerce blacklisted 24 state-owned companies involved in the construction of China's seven artificial islands in the Spratlys.

Since December 2019, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines have all submitted note verbales to the UN rejecting China's nine-dash line and its claims to "historic rights" in the SCS to be inconsistent with UNCLOS.

Southeast Asian reactions

Southeast Asian countries have watched with mounting concern the growing discord between the US and China. Most regional states have endeavoured to maintain productive and cordial relations with both superpowers and avoid taking sides. Nevertheless, the Southeast Asian claimants have been perturbed by China's assertive behaviour in the SCS during the pandemic and, to varying degrees, have hardened their positions.

Lawfare has been their primary response. Since December 2019, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines have all submitted note verbales to the UN rejecting China's nine-dash line and its claims to "historic rights" in the SCS to be inconsistent with UNCLOS. More significantly, in rejecting China's claims, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines explicitly referred to the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling, thereby effectively resurrecting the award after four years of it being put to one side. Even Brunei, long considered the "silent claimant", issued its first unilateral statement on the SCS on 20 July which emphasized that negotiations to resolve the dispute should accord with UNCLOS. Under Vietnam's Chairmanship this year, ASEAN has also placed greater emphasis on UNCLOS as the "basis for determining maritime entitlements, sovereign rights, jurisdiction and legitimate interests over maritime zones". However, to avoid antagonising China, none of the ASEAN countries explicitly endorsed Pompeo's statement, though Vietnam came the closest.

In addition to their UN submissions, Vietnam and the Philippines protested to China over the sinking of the Vietnamese fishing boat and the creation of the two new administrative districts in the SCS in April, while Vietnam rejected China's annual fishing ban.

Among all the claimants, the Philippines has hardened its position the most. In May, the navy opened a new docking facility on Pag-asa Island in the Spratlys and announced plans for further infrastructure developments. On the fourth anniversary of the Arbitral Tribunal ruling, Foreign Secretary Teddy Locsin said the award was "non-negotiable", and after Pompeo's statement, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana called on China to comply with the ruling. Most notably, on 8 June, the Duterte administration announced that it was suspending the abrogation of the US-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement. According to Locsin, this was due to heightened tensions in the SCS. In August, Locsin stated that if the Philippines was attacked in the SCS he would invoke the country's 1951 military alliance with America, while Lorenzana called Beijing's nine-dash claims "imaginary". President Duterte himself, however, continues to downplay the issue. In his State of the Nation Address in July he said the Philippines could not afford to go to war with China to defend its claims. A week later, he banned the Philippine Navy from conducting combined exercises in Philippine waters with its US counterpart.

In accordance with its longstanding policy, Indonesia reiterated its rejection of the nine-dash line and China's offer to negotiate their 'overlapping' claims near the Natuna Islands. In July, the Indonesian armed forces conducted a major naval and air exercise off the Natunas in a show of resolve to defend the country's maritime rights.

Malaysia has taken a characteristically low-key approach to rising tensions. The Malaysian navy and coast guard patrolled close to the West Capella drilling ship and monitored the presence of the Chinese survey ship in its EEZ during April and May, while the government reiterated that it would safeguard the country's rights and interests in the SCS. Kuala Lumpur also called on all parties to cooperate to ensure peace and stability and warned of the dangers of accidental incidents caused by the presence of foreign warships.

What happens next?

Worsening US-China rivalry

The escalating strategic rivalry between the US and China will continue to inflame tensions in the SCS. Discord between the US and China could increase markedly in the run-up to the November 2020 US presidential election. Given the bipartisan consensus in America over China, a future administration led by President Joe Biden would be unlikely to adopt a more conciliatory policy on the SCS. If President Trump wins re-election, his administration will continue its hardline policy towards China in the SCS.

In 2020-21, therefore, we can expect to see a higher tempo of US military operations in the South China including presence missions, overflights, exercises and FONOPs. Further US sanctions can be expected to be imposed on individuals and companies from China that Washington accuses of implementing Beijing's policies in the SCS.

China will double-down on its territorial and jurisdictional claims in the SCS and ramp up pressure on Taiwan. This is designed to bolster President Xi's nationalist credentials and divert attention away from China's economic problems.

Through its naval deployments in Malaysia's EEZ and Pompeo's statement, the US has shown that it intends to increase support for the Southeast Asian claimants. This is likely to include the transfer of equipment such as radars, drones and patrol boats so that they can better monitor China's activities in their EEZs, specifically illegal fishing and the presence of Chinese government vessels. Pompeo has also indicated that the US might be willing to provide legal support to the Southeast Asian claimants.

China will double down on its territorial and jurisdictional claims in the SCS and ramp up pressure on Taiwan. This is designed to bolster President Xi's nationalist credentials and divert attention away from China's economic problems. As such, the size and frequency of PLA-Navy exercises in the SCS will grow. China will not be deterred by US military activities, including FONOPs. As the frequency of FONOPs in the SCS increases, the PLA-Navy might adopt a more confrontational response to US Navy vessels that transit through the Spratlys and Paracels, raising the risk of an incident at sea which could trigger a political-military crisis in US-China relations.

China will continue to deploy survey vessels into the EEZs of the Southeast Asian claimants and harass vessels chartered by those countries to engage in exploration and drilling activities. The purpose of this harassment is to coerce Southeast Asian governments into signing joint development agreements with China while discouraging international energy corporations from participating in offshore oil and gas projects with Southeast Asian energy corporations without Beijing's approval.

China, however, considers that its so-called "historic rights" in the SCS trump UNCLOS and that the Arbitral Tribunal ruling is invalid.

Southeast Asian options

The Southeast Asian claimants are determined to uphold their territorial claims and sovereign rights in their EEZs. They are equally determined not to be drawn into a spat between the US and China over the contested waters. Due to massive asymmetries in power, the Southeast Asian disputants cannot use their navies or coast guards to confront the PLA-Navy or CCG - only to monitor their activities. Going forward, their ability to do so may be further reduced as regional governments are forced to cut defence spending due to the Covid-19-induced economic crisis and divert limited naval and maritime law enforcement assets to tackle rising piracy and sea robbery attacks.

The Southeast Asian claimants are left with two policy options, neither of which is likely to deter Chinese assertiveness.

The first is to continue emphasising that their maritime rights are determined by UNCLOS, rights which were upheld by the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling. China, however, considers that its so-called "historic rights" in the SCS trump UNCLOS and that the Arbitral Tribunal ruling is invalid. Southeast Asian strategies that seek to shame China into bringing its claims into line with UNCLOS will not succeed and Beijing will be prepared to absorb the reputational damage.

As such, the CoC may not be signed until 2022 or 2023, by which time China will have greatly consolidated its position in the SCS.

The second is to negotiate a CoC between ASEAN and China in the hope that it will mitigate Beijing's behaviour and reduce tensions. However, due to the pandemic, so far this year officials from the ten ASEAN member states and China have been unable to meet to continue negotiations for the Code.

In July 2019, officials agreed on the first reading (first draft) of the CoC. The last meeting of the ASEAN-China Joint Working Group (JWG) on the CoC was in Da Lat, Vietnam, in October 2019. Two JWG meetings scheduled for early 2020 - in Brunei in February and Manila in May - were cancelled due to the coronavirus. The sensitive nature of negotiations has not allowed for talks to be conducted by videoconferencing. This situation may change later in the year and virtual talks on less sensitive aspects of the CoC may occur. Beijing seems keen to resume talks.

However, even if discussions do resume, the hiatus in the JWG's work means that China's unilaterally imposed deadline of finalising the CoC in 2021 will not be met. Even before the onset of the pandemic, several ASEAN members had already expressed doubts about the likelihood of meeting this goal, given the complexity of the issues under discussion. As such, the CoC may not be signed until 2022 or 2023, by which time China will have greatly consolidated its position in the SCS.

Possible but unlikely scenarios

There are several possible though unlikely courses of action that China and Vietnam might undertake in the SCS over the next 18 months.

China turns Scarborough Shoal into an artificial island

Retired Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines, Antonio Carpio, has predicted that Beijing will terraform Philippine-claimed but Chinese-occupied Scarborough Shoal into its eighth artificial island in the SCS before President Duterte leaves office in 2022. Carpio has claimed that China needs to build military facilities on Scarborough Shoal - such as radars, communications equipment and a landing strip - before it can establish a comprehensive Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the SCS. However, China is unlikely to reclaim Scarborough Shoal before Duterte's term ends due to the severe damage this would inflict on Sino-Philippines relations which, notwithstanding a slight hardening of Manila's position, have improved significantly since 2016. Moreover, any move by China to send a fleet of dredging vessels to Scarborough Shoal would likely provoke a strong counter-response from the US, possibly including intervention by the US Navy to prevent reclamation work from taking place.

Although China has built extensive military facilities on its seven artificial islands in the Spratlys, since they were completed in 2016, the PLA-Air Force has not deployed combat jets to the three features that host air strips (Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef and Subi Reef).

China establishes an ADIZ over the South China Sea

In May, Taiwan's Ministry of National Defense suggested that China was preparing to announce the establishment of an ADIZ over the whole or parts of the SCS. While China has undoubtedly prepared plans for a SCS ADIZ, it has refrained from implementing them for two reasons. First, an ADIZ would lead to a significant escalation in tensions with the Southeast Asian claimants - especially Vietnam - and the US, Japan and European countries. Second, and perhaps more importantly, an ADIZ would be largely symbolic as China would face severe difficulties enforcing it over such a wide area. Although China has built extensive military facilities on its seven artificial islands in the Spratlys, since they were completed in 2016, the PLA-Air Force has not deployed combat jets to the three features that host air strips (Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef and Subi Reef). One possible reason is that the structural integrity of the runways is suboptimal and the PLA-Air Force does not want to risk an embarrassing mishap involving one of its fighter jets taking off or landing. Without utilising the airstrips on its artificial islands, China's air force cannot sustain combat patrols over the SCS for extended periods of time due to a shortage of heavy aerial refuelling tankers. Over the medium to long term, however, a Chinese ADIZ over the SCS remains a strong possibility.

Vietnam takes legal action against China

Over the past few months there has been speculation that Vietnam is considering launching legal action against China over its jurisdictional claims and activities in the SCS under Annex VII of UNCLOS, as the Philippines did in 2013. Vietnam has never ruled out legal action against China and in November 2019 Deputy Foreign Minister Le Hoai Trung told an academic conference that it remained one of several options open to the government.

Vietnam's case would be different from the Philippines' in that it would probably challenge China's straight baselines around the Paracels and violations of Vietnam's sovereign rights in its EEZ. Although it remains an option, Hanoi is unlikely to pursue it for several reasons. First, China would consider it an extremely hostile act and impose punitive measures against Vietnam - economically, along their joint land border, and in the SCS. Second, the Vietnamese leadership will be preoccupied in the run-up to the 13th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) which will take place in early 2021. Third, as with the Philippine case, China would refuse to participate in the hearings and reject any legal ruling.

Few grounds for optimism

There are few grounds for optimism that there will be an alleviation in tensions in the SCS in 2020-2021. The central dynamic is US-China rivalry which looks set to escalate. Faced with this hard reality, Southeast Asian states will have few tools at their disposal to mitigate the dispute beyond recourse to international law and multilateralism. As such, the SCS dispute will remain at the top of Southeast Asia's security agenda for the foreseeable future.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2020/97 "The South China Sea Dispute in 2020-2021" by Ian Storey.

Related: Amid domestic political change, Malaysia sticks to trusted formula for South China Sea disputes | Could China-US tensions in the South China Sea escalate into a hot war? | Indonesia crosses swords with China over South China Sea: 'Bombshell to stop China's expansionism'? | Should Vietnam file a case against China's maritime claims in the South China Sea? | [South China Sea] Should the Philippines avoid playing the lead role amid rising tensions in SCS?

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)