János Kornai: A Hungarian insight into China's economic development

Prof Chen Kang opines that after over 40 years of reform and opening up, China is still heavily influenced by the planned economy of its past. China is also stamped with characteristics of market socialism, as its early reform is modelled after the Hungarian experience. Hence, Chen suggests that China should heed the warnings of the eminent Hungarian economist János Kornai, as it takes its next steps forward in its economic reform.

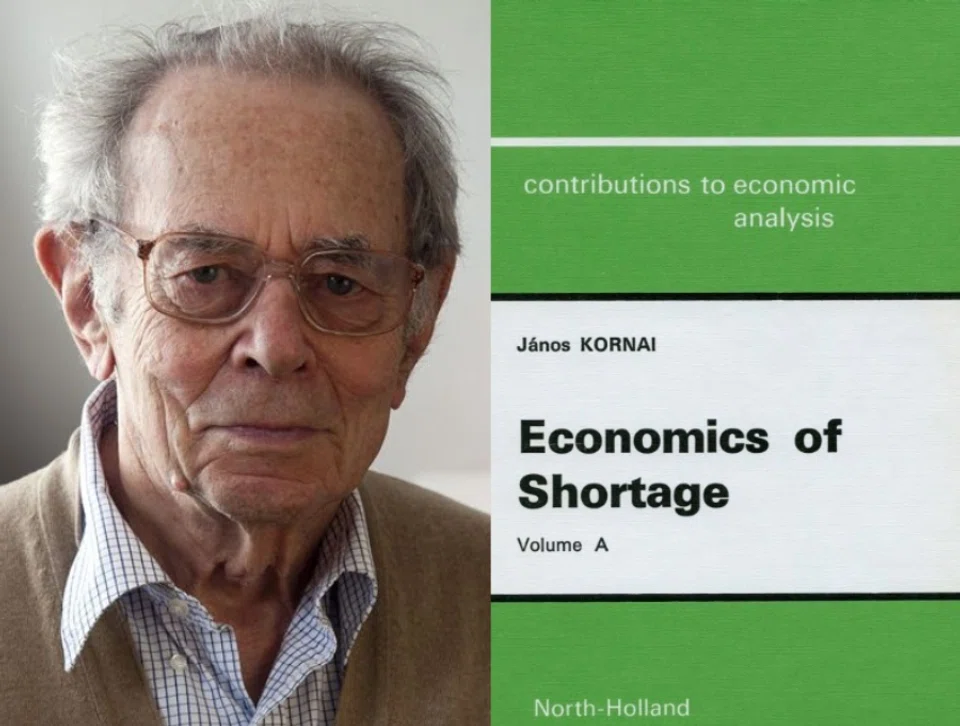

János Kornai is a renowned Hungarian economist. His seminal work, Economics of Shortage, took former socialist countries by storm when it was published in 1980. It provided an analysis of the systemic problems behind the shortages created by a planned economy. A goods shortage then was the norm. Empty store shelves were seen all over the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. When the shelves were (rarely) replenialso shed, long lines would form outside the stores. In China, ration coupons were widely used. There were coupons for grain, cloth, cooking oil, meat, fish and matches - very few items did not require rationing.

At that time, China's planned economy was undergoing reform, and it was "crossing the river by feeling the stones" (摸着石头过河, a famous saying coined by Deng Xiaoping). Naturally, Kornai's theory would have attracted the attention of Chinese economists. Moreover, Hungary was among the earliest socialist countries to embrace economic reform, having experimented with market socialism under "New Economic Mechanism (NEM)" in 1968. Thus, Chinese reform leaders were keen to know more about Hungary's experience.

Hungry for experience

In 1983, a Hungarian economics delegation visited China on an official trip to share the Hungarian experience in economic reform with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the State Commission for Restructuring the Economic System (an entity absorbed into the National Development and Reform Commission of the People's Republic of China in 2003).

In 1985, ten foreign economists, including János Kornai, were invited to the Bashan Lun river cruise conference to offer advice for China's economic reform. The conference had a huge impact on setting the proposed target model for China's economic reform encapsulated in the slogan: "The state regulates the market and the market guides enterprises", coined during the 13th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.

With the fall of the Soviet Union and transition to a market economy in Eastern Europe, as well as economic reform in China and Vietnam, the shortage economy ceased to exist in the 1990s. Times have changed and most people today would have forgotten about the shortage economy, not to mention Kornai and his Economics of Shortage.

However, we should not forget Kornai. People nowadays are used to using "state capitalism" to describe China's economy. Yet, Stalinism, anarchism, Trotskyism and Italian fascism have all given their definitions of this concept before. Moreover, apart from China, countries like Norway, Singapore, Russia during Putin's reign, and the US when it was in a financial crisis, all had the label of state capitalism plastered on them.

Hungary's New Economic Mechanism still relevant

If one were to only focus on the state ownership of the means of production, and neglect fundamental differences in the political and legal systems, the grossly misused term has no practical use at all - apart from its common use by leftists to attack policies of reform and opening up.

Today's China emerged out of a centrally planned economy. The political system of this single-party state is not too different from the period before it underwent reform and opening up. In fact, it's more similar to the time when Hungary implemented market socialism. Thus, an extensive analysis of market socialism's operating mechanism would help one understand China's economic outlook better than the label state capitalism would.

After over 40 years of reform and opening up, China is still unable to completely rid itself of the influence from its past planned economy. In addition, as it modelled after the Hungarian experience in the early phases of its reform, China is heavily stamped with the characteristics of market socialism. Although its market-oriented reforms went further than what Hungary did in the 1980s, China retained three important characteristics of Hungary's NEM period: investment hunger, soft budget constraint, and simulated capital market.

Investment hunger

Although Hungary abolished mandatory planning after implementing market socialism, the government continued its frequent intervention in enterprises in a bid to achieve an organic integration of central management and market forces. For enterprise managers, this resulted in a dual dependence of "seeing the market with one eye, and watching the superiors with the other". Compared with the market, their superiors undoubtedly had more influence on them. Thus, enterprises and organisations developed a strong drive for investment expansion, in an attempt by these managers to grow their enterprises or organisations and make them more important. This sort of investment expansion is not profit-driven, but to enable managers to climb the bureaucratic pyramid. Kornai describes such a drive for internal expansion as "investment hunger". He observes that the easiest way to expand is through investments in heavy industries and mammoth projects.

...investment decisions are inevitably influenced by senior bureaucrats and sometimes even carried out as a political mission.

China's economy today has also retained dual influence on enterprises from both the government and the market. Although state-owned enterprises must cater to market needs, political masters' decisions still reign supreme - they hold the decisive role in business management environment, personal remuneration and promotion. Thus, investment decisions are inevitably influenced by senior bureaucrats and sometimes even carried out as a political mission.

More importantly, China's investment hunger has, to a great extent, shifted from state-owned enterprises to the local government. As "assurance of economic growth" (保增长) has become an important performance indicator, investment projects of the local governments have become the main means of ensuring GDP growth. Apart from aligning their strategies with the central government's industrial policies and developing the region's infrastructure, investment projects that serve to accrue performance appraisal for leaders of local government but do not generate acceptable economic return and social benefits are often eagerly undertaken - as a result, the insatiable hunger for investment has become a new trademark of Chinese cities.

Soft budget constraint

In an actual market economy, even if enterprises have the drive to expand, their investment activities are constrained by consideration of returns, risks, budget, as well as disciplines of the capital market. In market socialism, Hungary's state-owned enterprises maintain their ability to utilise its administrative relationships and political influence to obtain approval for investment projects and funding. Their investment hunger and expansion drive are hence satisfied and not constrained by the enterprise's own budget. Kornai labels this phenomenon as "soft budget constraint".

...local governments are stuck in a dilemma - GDP growth is not to be worshipped uncritically, but neither can it be forsaken.

Similar to investment hunger, China's soft budget constraint has also shifted from state-owned enterprises to the local government. In the mid-90s, China even attempted to draw a line between fiscal and financial systems to strengthen the government's financial discipline by clearing off the bad debts of state-owned banks. However, between 1997 and 2002, deflation forced the government to prioritise an assurance of economic growth.

Under the slogan: "Ensuring a GDP growth of above 8%" (保八)", local governments did all that they possibly could to satisfy their investment hunger - from large-scale development of land finance, utilising local governmental financing vehicles, to various undertakings of government debt. Similar to state-owned enterprises of Hungary, Chinese local government investments virtually faced no budgetary constraints.

The central government often sent out multiple warnings and commands to local governments against carrying debt, but they clearly understood that "no matter how capable a woman may be, if she does not have rice, she can't cook" (巧妇难为无米之炊) - local government investments must be increased to sustain economic growth, but without the guarantee of funding, assurance of economic growth by local governments is but empty talk. In recent years, although the central government has been emphasising a change in the way growth shall be achieved and has strengthened its control over government debt, local governments are stuck in a dilemma - GDP growth is not to be worshipped uncritically, but neither can it be forsaken. Hence, soft budget constraint lasts until now, and government debt is constantly accumulating.

Simulated capital market

Hungary's market socialism advocates state control over the main sectors of the economy or what Lenin called "the commanding heights", convinced that this is the basic guarantee for social stability. Such control also includes the control of capital and its distribution. However, the government also attempted to inject some features of capital markets into the system, activities that Kornai calls "simulated capital market".

Kornai points out: "A Westerner who hops over here for a couple weeks from, say, the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund may fall under the spell of these simulations ... Odds are he will not notice that these same banks, joint stock companies, or the stock exchange are but fakes. What is going on here is a kind of peculiar "Monopoly" game, in which the gamblers are not kids but adult officials, who do not play with paper money but risk real state funds."

China's capital market reform is not only more thorough than Hungary's, the proportion of non-state funds in the Chinese market is also larger. Yet, the nature of the simulated capital market has not been fundamentally changed. According to a 2018 report by Liu Shaofang and Sun Haibo, China's Ministry of Finance is a major shareholder of China's "Big Four Banks" - the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, and the China Construction Bank - holding over 50% of their shares. All 12 joint-stock (commercial) banks of China, apart from Ping An Bank and Minsheng Bank, are either owned by the Ministry of Finance, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, central state-owned enterprises, or the local governments.

Lucrative businesses are either not done, or have to be abandoned, while businesses that are sure to make a loss, resolutely undertaken.

Urban commercial banks and rural commercial banks are basically controlled and owned by the local governments. Among the top 30 securities company with the largest assets, 27 are controlled by state-owned enterprises. Among 68 trust companies, 52 are practically controlled by central state-owned enterprises or the local government. Among the top 50 fund company with the largest assets, 70% are controlled by the central or local governments. All insurance companies, except Ping An Insurance, are controlled by the government. The government not only controls the majority of financial institutions, it also possesses the power of appointment and removal of executives.

While cross-ownership of stakes may be a complicated matter, the current circumstance of a simulated capital market is not cast away and many transactions are not completed in the name of profit. Lucrative businesses are either not done, or have to be abandoned, while businesses that are sure to make a loss, resolutely undertaken. Additionally, it remains a big uncertainty as to whether a contractual counterparty would be bailed out by the government if it defaults. When risks cannot be appropriately assessed, it is difficult for financial products to be reasonably priced.

Implications

The aforementioned three characteristics of market socialism are closely related to one another. If we were to truly allow the capital market to hold a decisive role in the allocation of financial resources, financial market discipline would disallow fiscal overdraft; local governments would be greatly limited in their access to financial resources, resulting in the inability to sustain soft budget constraint; and thus, investment hunger will be effectively curbed.

But are countries that advocate market socialism willing to give up their control over the distribution of financial resources and allow the capital market to operate effectively? Kornai believes that they are not, because of the following four reasons: firstly, state-owned enterprises and local governments form the basis of the state's political power; state governance depends on them. Without the guarantee of financial resources, the state's executive ability or state capacity will be greatly discounted, and they will fail to portray the superiority of socialism.

Secondly, although the market helps improve efficiency, socialism emphasises equality and protects the rights of the weak. Thus, socialist ideology has already determined that the market is not king and the government has to interfere with the capital market. Thirdly, with a property rights structure that is based on the dominance of public ownership, it is fated that the soft budget constraint is here to stay. With the bureaucrats having control over the assets of state-owned enterprises and local governments, and funds coming in and out of the state's different pockets, it is difficult to expect bureaucrats to impose strict financial discipline on themselves. Fourth, the interference and control exercised by one's superiors and the government have provided managerial workers with leeway to absolve themselves of their mistakes, making it even tougher to impose tight budgets.

Deng Xiaoping once said, "A market economy is not capitalism, because there are markets under socialism too." Of course, the amount of market activities allowed under socialism is still determined by the government. The problem is, the government is made up of tens of thousands of bureaucrats. These bureaucrats decide the extent of governmental interference in various industries and regions based on their personal interests and preferences. Any slight change in the political climate is enough to create a major difference in the market environment.

Chinese economists in the 80s generally believed that China's economic reform must be carried out in two steps: the economy's coordinating mechanism must first be transformed from a direct bureaucratic control to an indirect one, and then be further transformed to market coordination with macro-control. Kornai had already warned then that a socialist economy mainly based on the dominance of public ownership is actually incompatible with market mechanisms. There is a high possibility that once economic reform has reached the "indirect bureaucratic control" stage, it will henceforth become stagnant. Why does China choose to be more tolerant of the leftists' cries in recent years? Why are there desires for state-owned enterprises to become even stronger and bigger? Why must non-establishment forces be subject to more strict control? Why is the reform of the capital market all talk but little action? Kornai's warning can lead us to the answers to these questions.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)