In China, you are your score

Bram Barclay points out that the frenetic, results-based model of Chinese education must change if future generations are to reap the benefits of a true education.

Tara Westover grew up in the shadow of a mountain. Born and raised in rural Idaho to a fundamentalist Mormon family, she spent much of her childhood canning peaches and prepping for the end of the world. Her father believed that the millennium would bring with it the apocalyptic scenes of the Book of Revelation. His kids grew up without a phone line, no access to formal medicine and without even having birth certificates. The millennium came and went, and the world did not end.

Tara had no formal education as a child. Most of her education came from bible study and helping her parents - her mother was a holistic healer who made essentials oils and herbal remedies and her dad was in construction and ran a junkyard out of his garden. However, with the help of one of her older brothers, she managed to self-study for the ACTs and managed to earn a place at Brigham Young University, a Mormon college in Utah. From there she impressed her professors enough to get enrolled in a summer programme at Cambridge University, where an essay she presented to a professor was so good he pushed her to apply for the prestigious Cambridge Gates scholarship. She eventually graduated from Cambridge with a PhD in History.

Her remarkable story is told in her bestselling memoir Educated. While it might not seem obvious what this story has to do with China, while reading it this summer I was reminded of a trip I took to a school in Anhui province a few years ago. A friend I had from Fudan University, in Shanghai, had been a teacher as part of a Yale teaching programme affiliated with the school. The school was at the foot of the Yellow Mountain.

There was a student that year that they called the 'study god (学神)'. He was the school's big hope of sending someone to the prestigious Beijing University (Beida) and so he was given special private lessons from the foreign teachers and was allowed to work on his own away from the other students. I saw him once, walking around the campus alone, flanked by a teacher. All the other students were at their desks.

The gaokao (高考) or national college entrance exam in China is infamous in terms of its brutal difficulty and its unequivocal harshness. Unlike in the West where college applications are generally considered on the overall qualities of a candidate - such as their personal statement, references, extracurricular activities and charity work - in China a child's score on the gaokao is always the determinant factor (unless they've been hand-picked by a school on the basis of something like winning a national science competition or maths Olympiad or a particular sporting or musical talent).

You are your score. For some, like the study-god, this meant the potential of bringing a huge amount of prestige to the school and propelling himself from a tiny town in Anhui to one of the top universities in the country. It would have completely altered his life course.

Education reform in China is an incredibly fraught topic. As I noted in an earlier column, Jack Ma recently commented that education needs to be changed in China to reflect the dynamic needs of a rapidly automating and digitising economy.

These comments are part of a global trend questioning the validity of traditional subjects like history or maths as they are traditionally taught, in favour of courses like coding and robotics which seem better suited to the 21st century. People also question the idea of 4-year undergraduate programmes, insurmountable levels of student debt, and degrees which have little practical value in the marketplace. Vocational courses and shorter degrees taken throughout the life course are some of the remedies that have been suggested.

More importantly, what needs to change is the entire understanding of what an education is. In Educated, Ms Westover makes an argument for an education as the expression of individual personhood.

In 2012, Shanghai schools topped the international PISA ranking in maths. Suddenly the world wanted to know the secrets of the 'Chinese education model'. But for people in China, the ranking belied their anxieties about the system. It could produce results, but at what cost? In my anthropological work into mental health in China, I often speak to affluent people who are still, even decades removed from their high school experience, somewhat traumatised by the intense pressure that they were under. Parents often complain to me that they know the system is broken - and that it is breaking their children - but they feel powerless in the face of it. When people are competing so hard for the extremely limited spaces that exist at elite schools in China, it creates a treadmill that is extremely difficult for anyone to step off.

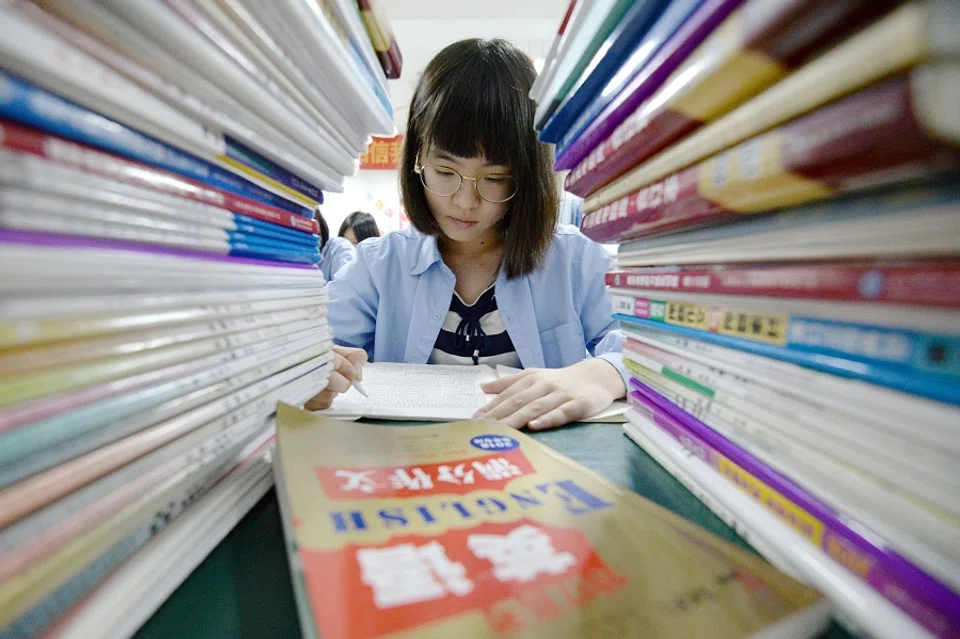

In that school in Anhui, I was taken down into the basement beneath the main school building where they had stacked up all of the lockers that had previously been at the back of the classrooms. The principal had calculated that each day students 'wasted' 15 minutes a day going to and from their lockers. 15 minutes a day, six days a week was an hour and a half. An hour and a half added up to 12 hours a month. The lockers had to go. The students sat with all their books piled on their desk like teetering towers. The students wouldn't get up between lessons to get new books; they'd remain seated and reach for the necessary books from the pile. 15 minutes a day saved.

Richer parents send their children abroad if they can afford it and if the child has a decent enough level of English or whatever language is necessary for the target country. For the rest who are stuck in the system, it is incredibly difficult to advocate for change. Those who have succeeded within the system argue it is meritocratic and the only way you can propel someone from rural Anhui to the upper echelons of society. This, of course, is not strictly true - affluent parents who don't send their kids abroad have the advantage of spending on tutors, and students in cities like Beijing and Shanghai have better chances of sending their children to colleges in those cities, which are much better than those elsewhere in the country. Still, the perception of meritocracy is enough to create an intractable discourse against change.

There is also the practical consideration of what would replace the gaokao. It seems unlikely that other systems would be any more meritocratic or fairer - just look at America's college admissions scandals this year which saw rich parents paying for people to take their kids' exams and photoshop them onto the photos of professional water polo players and you get the idea.

More importantly, what needs to change is the entire understanding of what an education is. In Educated, Ms Westover makes an argument for an education as the expression of individual personhood. She grew up in an abusive family. As she notes, her education allowed her to return and face them as her own person. I was struck that despite getting a PhD from Cambridge, the book didn't overly dwell on the practical or material benefits this had construed on her. We never learn what job she ended up doing after college or how it had helped her earn more money. Instead, she says, "Everything I had worked for, all my years of study, had been to purchase for myself this one privilege - to see and experience more truths than those given to me by my father, and to use those truths to construct my own mind."

It's a de-instrumentalised vision of education at its purest. An education that is not about passing an exam or getting to a particular place. It is education as a journey - not a destination. This education propelled Ms Westover over the mountain she grew up in the shadow of.

In another country, another student toils away under another mountain. Sometimes I think of that school at the foot of the Yellow Mountain, and the study god I saw walking on his own. I wonder where his education took him.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)