[Big read] Myanmar’s election: Beijing plans, ASEAN stalls, youth pay the price

Myanmar holds elections while Beijing charts its long game and ASEAN stalls. On the ground, young people flee conscription and insecurity, bearing the human cost of political manoeuvring far beyond their control. Lianhe Zaobao journalists Tan Jet Min and Zhou Yifei speak to academics and ordinary Burmese to find out more.

War-torn Myanmar is preparing to hold a general election. But political observers widely believe it will be a sham election, intended merely to legitimise military rule, rather than a genuine attempt to return power to the people. The international community, including ASEAN, views Myanmar as still plagued by violence and not yet ready for elections.

However, Myanmar’s two major neighbours, China and India, have not expressed clear opposition to the planned vote; from Myanmar’s perspective, the absence of objection amounts to support.

Tacit approval

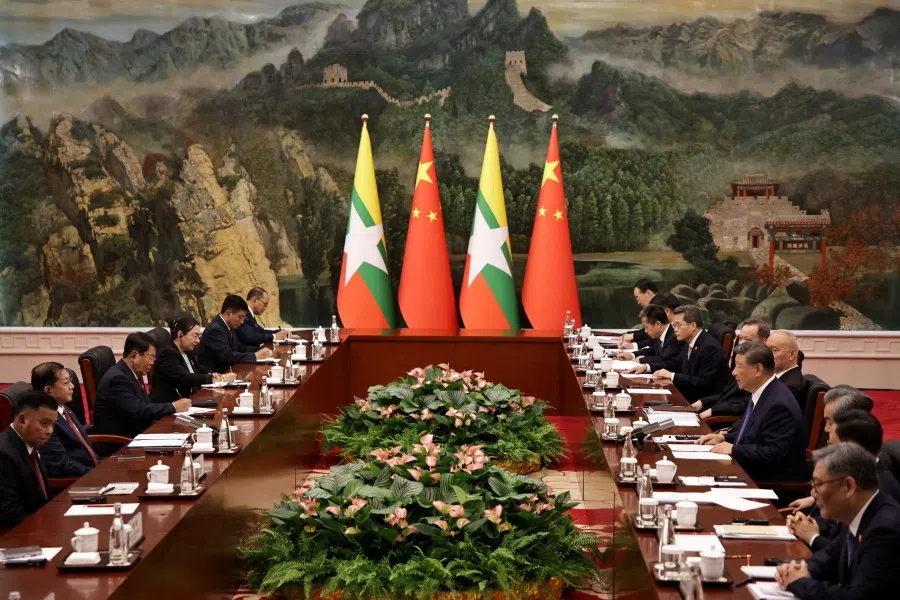

On 9 May, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Myanmar leader Min Aung Hlaing met in Moscow during the celebrations marking the 80th anniversary of the victory in the War of Resistance. Xi told Min Aung Hlaing that “China supports Myanmar in pursuing a development path suited to its national conditions, safeguarding sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity and national stability, and advancing its domestic political agenda in a prudent manner.” China did not explicitly endorse Myanmar’s holding of elections, but rather expressed support for the junta’s advancement of its internal political agenda.

On 14 August, Myanmar’s Foreign Minister Than Swe attended the 10th Lancang–Mekong Cooperation Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Anning city, Yunnan province. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi told Than: “China supports Myanmar in pursuing a development path that suits its national conditions and enjoys the support of its people, in upholding its sovereignty, independence and national unity, and in advancing its domestic political processes prudently. China will, as always, do its best to provide Myanmar with support and assistance.”

“... the only viable solution is gradual reform, not a complete revolution. A structured election is the most likely way to achieve this.” — Sun Yun, Director, China Programme, Stimson Center

Than Swe invited China to send a delegation to observe the election in Myanmar. Wang Yi did not indicate whether China would support this, but instead expressed the hope that Myanmar would achieve three goals through the election: “First, domestic peace with a cessation of hostilities among parties and national governance based on the will of the people; second, national reconciliation and broadest solidarity and third, social harmony, advancement of post-earthquake reconstruction and economic development, and improvement of people’s lives.”

Min Aung Hlaing and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi also met in late August in Tianjin during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit. Modi merely stated that the election must be fair and inclusive, with participation from all stakeholders.

It is noteworthy that Modi later wrote on Facebook that he and Min Aung Hlaing agreed that there is “immense scope” to boost ties in areas including rare earths. This remark likely touched a sensitive nerve in China, because Myanmar’s rare-earth ores are almost entirely exported to China, especially medium and heavy rare earth elements that are critical for high-tech industries. These exports allow China to have a stable supply, self-sufficiency, and even leverage in the sector.

Beijing supports junta to safeguard core interests

Academics interviewed believe that China is, in effect, supportive of Myanmar holding elections. Sun Yun, director of the China Programme at Washington-based thinktank the Stimson Center, noted that after five years of fighting, Myanmar’s civil war is at a stalemate. Neither the military nor the opposition can defeat the other, and the country must find an alternative route out of the current impasse.

“Given that Beijing believes the Myanmar military cannot completely withdraw from domestic politics, the only viable solution is gradual reform, not a complete revolution. A structured election is the most likely way to achieve this.”

In reality, a relatively stable Myanmar is far more aligned with Beijing’s core interests in Southeast Asia than a fractured Myanmar.

Independent analyst David Mathieson, who closely follows Myanmar affairs, said: “China’s support for the election is certainly not motivated by democracy at all. I think Beijing sees the election simply as a potential process to get out of the current impasse.”

In reality, a relatively stable Myanmar is far more aligned with Beijing’s core interests in Southeast Asia than a fractured Myanmar.

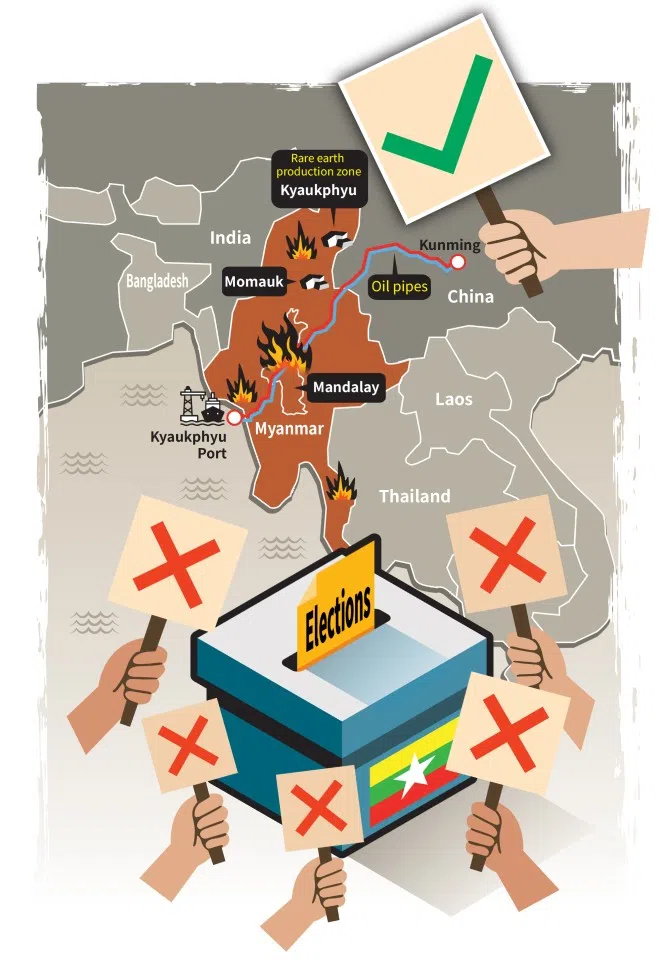

Beijing’s core interests include: ensuring the security of energy supplies and transport routes; protecting Belt and Road infrastructure and Chinese investments in Myanmar; combating cross-border scams and security threats targeting Chinese citizens; and limiting Western influence through strengthened economic and security ties, thereby safeguarding regional strategic interests.

A fracturing frontier breeding crime

At the end of 2023, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, the Arakan Army and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army formed the “Three Brotherhood Alliance”, posing a powerful challenge to the Myanmar military in multiple regions. Their gains boosted morale among other ethnic armed groups and the shadow government’s forces, and the military subsequently lost control of many territories. The civil war seemed close to overthrowing the military and achieving a successful revolution — but it also risked plunging the country into permanent fragmentation.

Such fragmentation is detrimental to Beijing’s interests in Myanmar, especially regarding Chinese investments such as the China-Myanmar oil and gas pipelines and the Kyaukphyu Port project, as well as the rise of telecom scam zones inside Myanmar, which have become a grave threat to China’s national interests and public security.

China has several key investments in Kyaukphyu, a major city in Rakhine State, including a large deep-water port and an oil pipeline running from Kyaukphyu to Kunming in Yunnan. During the civil war, the Arakan Army seized control of several major cities in Rakhine State; without Chinese intervention, Beijing’s interests there could be jeopardised.

... all sides are likely to tacitly allow transnational criminal syndicates to set up more and more scam compounds in order to profit from them.

Furthermore, if the Myanmar military continues to lose territorial control, and with both the military and ethnic armed groups needing funds to sustain the war, all sides are likely to tacitly allow transnational criminal syndicates to set up more and more scam compounds in order to profit from them. Telecom fraud has now metastasised into a stubborn cancer of international crime.

Richard Horsey, senior adviser on Myanmar at the International Crisis Group, believes that “China supports the elections because it would like to see a return to more predictable rule in Myanmar under the 2008 constitution, rather than the current emergency rule.”

ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute (ISEAS) senior fellow and ASEAN Studies Centre coordinator Joanne Lin noted that China seeks to maintain a certain degree of institutional and procedural normalcy in Myanmar to ensure the government can continue functioning.

In other words, only a stable and functioning Myanmar can prevent greater disruption to China’s interests in the country.

An election without reconciliation

However, the election pushed by the military has not involved inclusive dialogue or nationwide reconciliation, nor has it addressed the core contradictions driving the civil war. Whether the post-election period can bring peace and stability is therefore highly uncertain.

Liew Wui Chern, an assistant professor at the University of Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Department of Politics and International Relations, argued that for Beijing to help Myanmar achieve meaningful peace, it should facilitate trilateral dialogue among the military, the opposition and ethnic armed groups, and pressure the military to allow the exiled National Unity Government (NUG) to participate in the election, thereby enhancing its legitimacy.

However, the NUG has already made clear that it will not take part in any military-led election and has labelled it a sham, while the junta has forcibly dissolved Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, so that promoting inclusive dialogue among all sides in Myanmar is all but impossible.

ASEAN’s mediating role possibly undermined

China’s support for Myanmar is also reflected in the deepening exchanges and mutual visits between the two sides, with Xi Jinping and Min Aung Hlaing meeting in Moscow in May, and Min Aung Hlaing being invited to attend the SCO Summit in late August as well as the 3 September military parade, in his capacity as acting Myanmar president.

Min Aung Hlaing later told reporters with great pride that this was the most successful of his 12 trips to China over the years. His words reveal how, after being isolated by the international community since launching the 2021 coup, he finally feels vindicated.

The warming ties between China and Myanmar have made ASEAN’s marginalisation even more pronounced — or rather, it has highlighted ASEAN’s helplessness regarding the Myanmar crisis.

In September, Myanmar’s Prime Minister Nyo Saw met Chinese Vice-President Han Zheng at the China–ASEAN Expo; Myanmar’s Minister of Construction Myo Thant met Chinese Minister of Housing and Urban-Rural Development Ni Hong during the ASEAN-China Ministerial Roundtable on Construction; Myanmar’s Defence Minister Maung Maung Aye met Chinese Defence Minister Dong Jun at the Beijing Xiangshan Forum. These bilateral engagements have given the Min Aung Hlaing administration the international recognition it craves.

The warming ties between China and Myanmar have made ASEAN’s marginalisation even more pronounced — or rather, it has highlighted ASEAN’s helplessness regarding the Myanmar crisis.

ASEAN proposed its Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar in April 2021, but more than four years later, the consensus remains stuck on paper. ASEAN’s efforts to resolve the Myanmar issue have stalled, exposing its lack of real leverage over the military junta.

China’s support for the election may not only cloak Myanmar’s non-inclusive political process in a veneer of legitimacy, but also further weaken ASEAN’s standing and its ability to address internal problems.

“ASEAN cannot react with umbrage if China is making more ‘progress’ than the regional body, their regional efforts have been fruitless.” — David Mathieson, an independent analyst

Nanyang Technological University S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) associate research fellow Henrick Tsjeng said that if ASEAN succeeds in playing a guiding role in brokering ceasefires among Myanmar’s various parties or in reaching a peace agreement, China would not necessarily diminish ASEAN’s role. But if Beijing bypasses ASEAN and mediates unilaterally, it will inevitably weaken ASEAN’s relevance.

David Mathieson criticised ASEAN for being “weak” and “toothless” on the Myanmar issue. “ASEAN cannot react with umbrage if China is making more ‘progress’ than the regional body, their regional efforts have been fruitless.”

Close economic ties with ASEAN give China more influence

Beijing’s confidence in intervening in the Myanmar issue is rooted mainly in economic relationships and the broader geopolitical landscape. UTAR’s Liew noted that China maintains close economic ties with most ASEAN countries — an important source of political leverage that gives Beijing significant space to take the lead.

Moreover, because ASEAN states generally pursue a strategy of balancing between China and the US, Beijing believes it can take more exploratory political actions on Myanmar without jeopardising its relations with ASEAN members.

Although ASEAN hopes to advance the peace process in Myanmar, in practice it lacks effective channels to communicate directly with the military. China, in contrast, not only has long-standing familiarity and frequent interaction with the junta, but also maintains contact with some anti-junta forces and wields substantial influence over ethnic armed groups.

Still, ASEAN is not without value.

Junta craves acceptance from ASEAN

UTAR’s Liew pointed out that Myanmar’s military does, in fact, care about ASEAN’s stance and hopes to secure a minimum level of regional acceptance. This is evident from Myanmar’s continued decision to send non-political representatives to ASEAN meetings and summits each year.

A policy brief by the Peace and Conflict Resolution Evidence Platform at the University of Edinburgh recommended that although ASEAN is constrained by its principle of non-interference, it can still encourage the junta to implement the Five-Point Consensus. This can be done by strengthening diplomatic communication, institutionalising incentives, and coordinating pressure with international partners when the junta takes actions aligned with the consensus.

Yet while regional bodies debate principles and diplomatic tools, the reality on the ground in Myanmar is far more immediate and brutal. For ordinary people, the military’s escalating conscription drives and daily insecurity leave little room for abstract policy talk. It is in this harsh landscape — far from ASEAN meetings and international statements — that stories like Mu Mu’s unfold.

Mu Mu’s story: How I become a ‘monk’ to escape draft

At dawn, Mu Mu (pseudonym) put on monastic robes, carried 240,000 kyat (US$114) in cash, and boarded the regular bus bound for Yangon. As he handed the money to the checkpoint officers, his heart pounded. He silently prayed that the bribe would work.

The day before, Myanmar’s military had stormed into the village to seize able-bodied men. Mu Mu hid in a hole beneath a wooden house, his legs trembling uncontrollably. He held his breath as best as he could, desperate not to be discovered.

After the shouting and cries gradually faded, Mu Mu tearfully called his sister Xin Xin in Singapore. He told her that their cousin had been taken away by the military, that home was no longer safe, and that he was terrified.

In his early 20s, Mu Mu is tall and strong — “exactly the kind of young man the military most wants to seize”. To protect him, his family, who had already heard warnings, dug a hiding pit beneath their wooden house.

Xin Xin said: “I’m so relieved my brother wasn’t taken, but I also feel helpless. It feels like all I can do is send money home every month. I can only keep comforting him and support him in escaping to Yangon as soon as possible.”

Xin Xin, in her early 20s (pseudonym), is from Myanmar’s Magway region. Her parents are farmers, and she has younger siblings. She was the family’s first university student, whom everyone was proud of, dreaming of working in a government hospital after graduation. But the coup and civil war shattered everything. In 2023, she came to Singapore to work as a domestic helper.

Since the military overthrew the elected government led by Aung San Suu Kyi in 2021, Myanmar has been mired in civil war. Last year, anti-junta armed groups and ethnic armed organizations achieved a series of victories, forcing the badly weakened junta to resort to conscription to replenish its forces.

In his early 20s, Mu Mu is tall and strong — “exactly the kind of young man the military most wants to seize”. To protect him, his family, who had already heard warnings, dug a hiding pit beneath their wooden house. After learning that the military generally avoids arresting monks, they shaved his head and prepared monastic robes for him.

Others were not so fortunate. About 35 people from the village were taken away, including one of Xin Xin’s cousins. “To this day, I have no idea where he is — there’s been absolutely no news.”

When asked what she expects from the election, Xin Xin repeatedly shakes her head and waves her hands. “This election is just for show. It won’t change anything. It’s useless.”

China’s intervention in Myanmar late last year has, to some extent, altered the situation. In April this year, through a mix of pressure and persuasion, Beijing managed to get the Kokang Army to return control of the strategic Shan State town of Lashio to the junta. On 18 August, Myanmar’s Union Election Commission announced that the first phase of the general election would begin on 28 December.

While the military views the election as “the path to peace and democracy”, the international community criticises it as a means for the junta to entrench its power and exclude opponents. For ordinary people, it is simply yet another futile episode in a five-year saga.

When asked what she expects from the election, Xin Xin repeatedly shakes her head and waves her hands. “This election is just for show. It won’t change anything. It’s useless.”

Although Xin Xin is much better off financially now, life far from home is not easy. Because of tightened border controls, she has not returned home since moving to Singapore, and Mu Mu’s hopes of going abroad for work have also been put on hold. According to her, Myanmar’s economy and security situation are worsening — villages burned, farmland destroyed, and the military firing at civilians with impunity.

Still, Xin Xin remains hopeful about the future. She believes people are all working hard for the revolution and that Myanmar will eventually regain peace. She looks forward to the day she can return home and reunite with her family. When that time comes, she hopes to open a pharmacy and fulfil the dream she once had.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “国际质疑声下中国力挺 缅甸能靠大选突破困局?”.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)