Tan Kah Kee: The Confucian merchant's relevance in contemporary societies

Professor Wang Gungwu gave a keynote address at the Hwa Chong Centennial Insights Series 5 detailing his memories about prominent Chinese community leader, Tan Kah Kee. He shares from his personal experiences before elaborating on Tan's huge influence on the Chinese community, and what we can continue to learn from him.

Distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, friends of Hwa Chong; admirers of Tan Kah Kee.

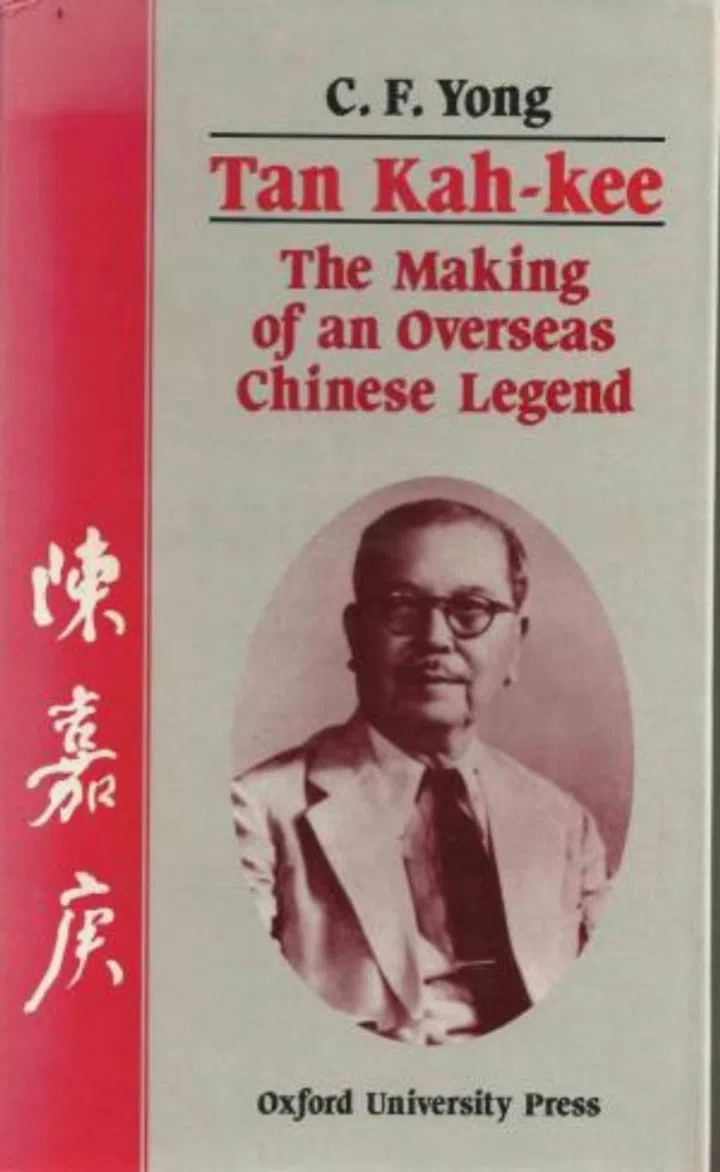

Thank you very much for inviting me to share my thoughts about Tan Kah Kee. I have opted to take the long view of his life to look at what my learning of his life - its richness - has meant for me. I had meant to pay tribute to the work of Professor Yong Ching Fatt and wish it had been possible to get him to come to give this keynote lecture. Sadly, he has just passed away. I therefore dedicate this talk to his memory, most of all to record my admiration for his wonderful study of Tan Kah Kee - the subject of our commemoration. His book is one that should be read by all who want to understand the contributions of those generous and big-hearted men and women who made a difference to the world in their lifetime. Professor Yong's carefully researched study has enabled us to understand this extraordinary man who has left such a deep mark on our history.

By calling mine a long view, I mean that I shall not only deal with Tan Kah Kee's own life and times, but also of the influence he had on so many people during the past 60 years since his death. I also expect that his example will continue to influence other lives for a long time to come. I shall not dwell on any of his specific achievements - you will be hearing from many experts in this room of the many kinds of contributions he made to Singapore and beyond. I shall speak first of my own experiences and then about what I believe his life stands for amongst people of Chinese descent everywhere.

My personal experience is illustrative of his influence. It began some 80 years ago when I was a boy in Ipoh, Malaysia. This was where my father spoke admiringly of Tan Kah Kee as the successful entrepreneur who gave away his money to support a variety of schools and the very fine university in Xiamen. My father's first job when he came to the Nanyang was to teach Chinese at Singapore Nanyang Overseas Chinese Middle School (新加坡南洋华侨中学). He had learned a lot about what Tan Kah Kee had done. He saw Tan Kah Kee as the epitome of the ru shang (儒商) - the merchants who had internalized Confucian values. He explained to me how such men not only valued education but also embodied the ideals of trust, thrift and industry that were at the core of Chinese culture. This gave me a picture of someone who believed that education would bring progress and advance the science and entrepreneurial knowledge that modern China desperately needed. I need hardly say that my father's admiration for Tan Kah Kee left a very deep impression in my mind.

My next memorable experience was, after I had made several visits to Xiamen University and admired the great institution that he had founded there, when I read Yong Ching Fatt's biography - The Making of Tan Kah Kee Legend. This was a masterly study of how the businessman became the community leader of the Chinese in our region. I am sure many of you have read the book and do not need me to take you through the fascinating story of how Tan Kah Kee became so respected by all who learnt about what he did. I only wish to add that Professor Yong did a remarkable job of placing his achievements in the larger context of the Nanyang and of a China in considerable distress.

In particular, I was made aware that here was someone who was very appreciative of the advances of science and the power of industrial capitalism; and that his patriotism and pride in things Chinese was also deeply imbued with the desire for China to be modern and progressive.

He also described British Malaya (in those days this included Singapore) at a time when it was adjusting to the carnage and destruction of two World Wars. How Tan Kah Kee navigated through those precarious years and came out of all that as the man who knew what to do to make things hopeful was a truly inspiring story.

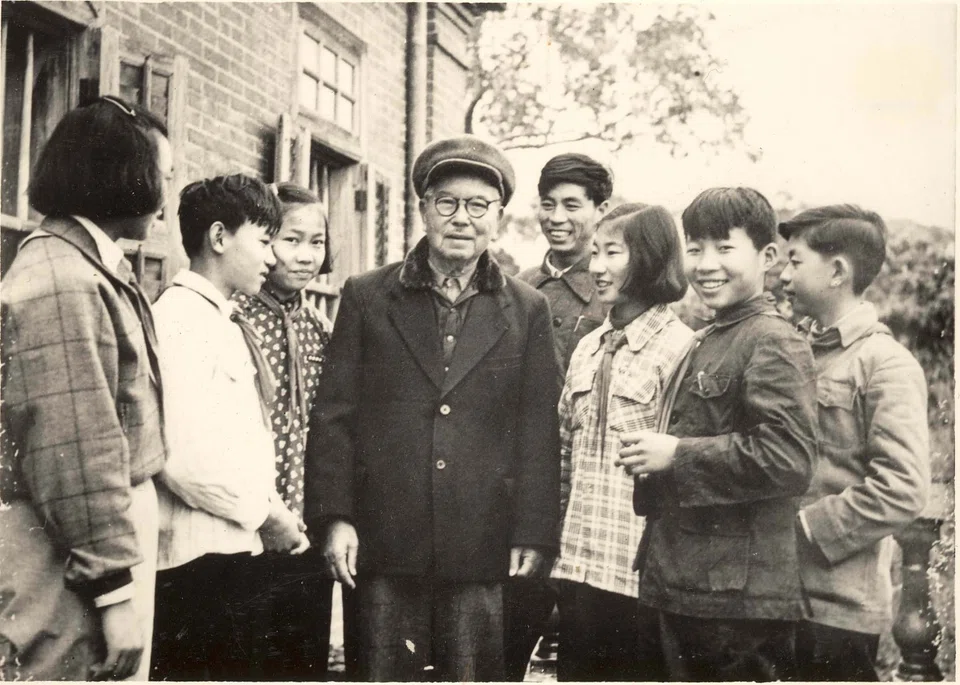

The third stage of my understanding came from several meetings with Tan Kah Kee's nephew, the late Tan Kiong Choon (陈共存). He eventually invited me to visit his hometown Jimei with him. Together we visited Ao Yuan Park where I paid my respects at Tan Kah Kee's grave. I heard the story of how the memorial was erected, the threats to it during the Cultural Revolution and the fine restoration work that was still going on. He took me around Jimei town - now a large town - to the many institutions associated with Tan Kah Kee and to the sites where different branches of the extended family, the many institutions associated with Tan Kah Kee, and to the sites where different branches of the extended Tan family lived, including the ancestral home of his kinsman Tan Lark Sye. He then took me across to Xiamen island to visit the university again. Although I had visited the campus before, this time I came away with a deeper appreciation of what Tan Kah Kee's legacy was really like. The introduction to his village origins, his family heritage and the impact that his life had on the whole community left me with a sense of awe. In particular, I was made aware that here was someone who was very appreciative of the advances of science and the power of industrial capitalism; and that his patriotism and pride in things Chinese was also deeply imbued with the desire for China to be modern and progressive.

A few years later, Tan Kah Kee came alive for me again when I was in Hong Kong. This was when I read about the World Chinese Entrepreneurs Convention founded by the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and inaugurated by the former Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew. Two years later in 1993 when I was asked to give the keynote address at the second convention meeting in Hong Kong, my first thought was that Tan Kah Kee was the real inspiration for that convention. He was not only one of the founders of the Singapore Chamber; he was also one of the earliest global Chinese entrepreneurs that the Nanyang produced. His products were traded around the world and this gained him a high reputation internationally for his adventurous outreach.

The only strategy that would not have appealed to him was to move away somewhere else where he might have thought was safer and freer. His life showed that he was not that way inclined. He was instead someone who would have stayed on to fight for what he thought was right.

At the same time, his extended business also made him vulnerable to global economic forces beyond his control. For that he had to pay a heavy price when he was exposed after the financial crash of 1929. What is extraordinary, however, was how he was able to extricate himself from that world and reinvent the new man of political action. It was that challenge that brought out the great community leader who could take his message of saving China far and wide and moved thousands of people to join him. Thus when I was asked to speak at the convention, I thought I should talk about the enterprise strategies that people like Tan Kah Kee might have chosen from in the 20th Century and went on to wonder what people who want to follow him today might choose.

Let me briefly outline the four strategies that came to mind at the time in 1993.

Make your fortune abroad and take that back home in order to benefit your extended family, and the wider community of city, province and country. That was the way to be a good hua qiao (华侨).

Reinvest locally and seek the best way for your new home country to prosper. To do that you would have to engage with your fellow citizens at every level and identify fully with their future.

Be ready to move away from where you live and work when conditions no longer satisfy you. Be prepared to go to some other place that you think might be freer and safer, and where the chances of retaining your Chinese identity are greater.

Use your skills to build local community power and enter the political arena if necessary in order to defend your rights as Chinese, even to the point of helping China to change and prosper.

Make your fortune abroad and take that back home in order to benefit your extended family, and the wider community of city, province and country. That was the way to be a good hua qiao (华侨).

Reinvest locally and seek the best way for your new home country to prosper. To do that you would have to engage with your fellow citizens at every level and identify fully with their future.

Be ready to move away from where you live and work when conditions no longer satisfy you. Be prepared to go to some other place that you think might be freer and safer, and where the chances of retaining your Chinese identity are greater.

Use your skills to build local community power and enter the political arena if necessary in order to defend your rights as Chinese, even to the point of helping China to change and prosper.

These thoughts came to me in 1993, twenty-two years after Tan Kah Kee's death. As I was sorting them out in my mind, I was conscious that the context had changed. The China that I saw from Hong Kong was reforming so fast that the Tan Kah Kee I admired would not have recognized it. However, I was sure that the transformations that were occurring would have had his strong approval.

For him, however, it was only the beginning of a dangerous political adventure that lifted his reputation higher than he could ever have expected.

Looking back to Tan Kah Kee's own lifetime, I thought that he started with the first strategy - the one that supported developments at home in China. But he then moved beyond that to the fourth strategy when conditions changed and he was gaining a national platform as a community leader. I also thought that he could have chosen the second strategy, that he was prepared to stay on to help to build a progressive Singapore. The only strategy that would not have appealed to him was to move away somewhere else where he might have thought was safer and freer. His life showed that he was not that way inclined. He was instead someone who would have stayed on to fight for what he thought was right.

25 years later - now from the vantage point of having lived in Singapore continuously for 23 years, my thoughts today about these four strategies are different. So much has changed in our two lifetimes. He was 56 years old when I was born and I am now 89 years old. When I put the two ages together, that is well over a century. When I first heard of him, he was about 65 years old, a good age when most people thought of quiet retirement. For him, however, it was only the beginning of a dangerous political adventure that lifted his reputation higher than he could ever have expected. After that, he became known not only locally, regionally, and in China, but also among other Chinese communities around the world.

With that background in mind, let me look again at the strategies that I had picked out in 1993. Clearly, strategy one is now the least likely for almost everybody. I cannot imagine many today who would bring their fortune back to China just to benefit family or country. In any case, the country China does not now need that kind of help any longer.

The second strategy, to prioritize development in one's chosen country over other possibilities has become the new norm. Anyway, most countries would expect that of its citizens, And national governments everywhere are promoting local enterprise and encouraging investments in projects that directly benefit the country. More importantly, the locals of Chinese descent are increasingly committed to their country's future, and more sensitive to the social problems that their fellow citizens encounter, especially to those who are needy and to those who are ailing and ageing.

Here we note that Tan Kah Kee was deeply involved from his young days in similar concerns with his hometown in Jimei. I am confident that today, he would be upfront in his vigorous and caring way with any community organization that could help his adopted country deal with such problems.

I am less certain today about the third strategy. That was the choice of many Chinese during the 20th century when empires were being replaced by new nations and some nations were more welcoming of immigrants than others and more tolerant of cultural differences. At that time, there was much talk of diversity and multiculturalism in many developed countries and many migrants voted with their feet in search of conditions that respected the autonomy of Chinese culture and education. However, that situation is more complicated today when China is actively promoting its culture overseas and many countries have become suspicious of the political content in those campaigns.

It is no longer enough to be a Chinese community leader and only represent community interests. It is now necessary to reach out to all those who have concerns beyond common ethnicity and culture.

What is to me particularly significant is the way the fourth strategy is playing out today. In Tan Kah Kee's time, community leadership paid little attention to national content in the imperial conditions that were prevalent in our region. It was largely a matter of representing one's own community in dealing with colonial officials and in cooperation or in competition with those who led other communities. The blocs of specific interests were usually well marked out by the colonial authorities in charge.

Today, there are national agendas that are much more focused. The regulatory systems that arise from different national goals can vary a great deal depending on the political forces that are ascendant at any one time. These conditions call for new kinds of responses, not least the willingness to participate in local politics When that is called for, issues go beyond Chinese community interests but must also include cooperative efforts among the different peoples resident in a particular district constituency.

In short, it is no longer enough to be a Chinese community leader and only represent community interests. It is now necessary to reach out to all those who have concerns beyond common ethnicity and culture. In order to gain local political influence, leaders of Chinese descent must understand a wider political spectrum as a whole and learn to share the trials and tribulations of all of society if they hope to succeed. This new world is still evolving, with some countries like Singapore more successful than others in providing conditions that favour those who choose to adopt this strategy. But there are testing times ahead. Global changes today require everyone to pay careful attention to social relationships if the conditions of multicultural harmony is what we want to promote.

Let me return to Tan Kah Kee, the man.

Yet, it was this obsession with education that contributed to his failure in the world of capitalist commerce and industry. He had used up too much of his working capital to survive the shocks of the Great Depression, and had to accept the unavoidable retreat from many of his business adventures.

Reading various books about him, I believe that he has often been misrepresented as someone who was no more than a Chinese patriot totally focused on China's interest. What is even worse is that he is sometimes seen as someone sympathetic to communism. People forget how lucky he was to have died in 1961 before the deadly political struggles in the People's Republic began. Some of those campaigns went on to destroy anyone who was suspected of not being supportive enough of the idea of unceasing class struggle and continuous revolution. That included anyone who was considered not to have been totally loyal to Mao Tse Tung. I hate to think of what would have happened to Tan Kah Kee had he lived for another five or more years and had to face the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution.

Here is where Professor Yong Ching Fatt's portrait is a vital corrective to the simplistic picture found in some other accounts of Tan Kah Kee's achievements. In his book, Tan Kah Kee comes across as the brilliant young entrepreneur who was open to new business ideas and methods, and fully determined to educate modern talent to meet current and future challenges. He was down-to-earth and alert and always looked out for opportunities to improve himself and his enterprises. He was not afraid to learn from experience and very quick to adapt to changing local and global economic conditions. For someone with only a traditional village education, he was exceptionally knowledgeable about the technical and marketing advances around the world. And he was ready to invest in all areas of education to ensure that the next generation would be better prepared for a progressive world. In his eyes, that was what he wanted most. Yet, it was this obsession with education that contributed to his failure in the world of capitalist commerce and industry. He had used up too much of his working capital to survive the shocks of the Great Depression, and had to accept the unavoidable retreat from many of his business adventures.

Ironically, it was this final failure in business that allowed him to turn all his energies towards a new life - one that lifted him above all others, and started him on his dedicated service to his people. He was aroused by what he saw of the mounting disasters in China as a country. He had observed the incompetence and corruption among Chinese politicians and officials. He had seen how the warlords and their continued fighting amongst themselves had attracted further foreign interventions in China, and finally led to the Japanese ambition to control the whole country. In those circumstances, Tan Kah Kee did not let his business problems defeat him. He was not the kind of person to simply complain and lick his wounds. Instead, he saw it as his duty to act and persuade others to join him in the cause of national reform. He succeeded beyond expectations at a time when the global economy was struggling to revive. What he achieved is now history. And it is one of the reasons why we are remembering this extraordinary man.

There are other speakers today who will explore the many facets of Tan Kah Kee's place in history better than I can. I shall confine my final remarks to asking two questions that interest me as a historian.

In what way was he the embodiment of something that had been evolving in China during the last few centuries, the rise of the ru shang - the Confucian merchant?

To what extent was he the product of a deep strand in Chinese thought - the dualistic outlook that always saw change occurring in what seemed like opposites?

There are now many good studies of how the ru shang emerged after the Song Dynasty. During the Ming Dynasty, the role of merchants was better appreciated. Confucianism had become more accessible to most families and many members of the trading classes had begun to learn how Confucian values could help them build business trust. Following that, Confucian mandarins in turn became more willing to cooperate with merchants to help the country's economic growth. In addition, merchants had discovered that they did well when they traded abroad among foreign officials who are more commerce-friendly.

With the opening of China in the 19th century, the Chinese saw how modern governments encouraged trade. This was a complex story that we all know but the results were enlightening. When mandarins were not obstructive and corrupt, Chinese entrepreneurs flourished and could successfully compete against foreign businesses, even those with imperial backing from their governments.

Tan Kah Kee was a good example of a local Jimei ru shang who married entrepreneurship to a strong sense of moral duty and social responsibility. That had prepared him well for a higher duty when his companies closed down and he could devote all his time to the enterprise of saving his town and province, and also, when called on, to help the country.

Late in his life, he proved how a ru shang could have a strong Confucian conscience and achieve even more because this could make him bolder and more enterprising. In this way, his example points to developments that updated what Confucianism used to stand for. He had provided resources for learning advanced ideas and mastering new methods to improve performance and thus push for higher attainment in everything that had to be done. My years in Singapore have shown me how this spirit of looking ahead can still be invaluable. If more people embrace his vision, the better the people of Singapore will perform.

My final point about dualism is a little more abstract, but I believe it is deeply embedded in Chinese culture, not least reflected in the way that Tan Kah Kee thought and acted. I refer to the way he and many other Chinese perceived the power of change in their affairs. This seemed to come from the way they internalized the assumptions behind China's great and oldest classic - The Book of Change; the I Ching (易经).

As I see it, the key rests in the idea that change is not linear, it is not mechanical, but could be self-determined through dialectical relationships of opposites. The normal representation of that idea takes the form of opposites acting on each other - like good and the evil (善恶 shan e); brightness and light (阴阳 yin yang); past and present (古今 gu jin).

Underlying that kind of action was the idea that good and evil could be reconciled, and that the darkness that followed light was not a disaster because light will return.

But they are not opposites set out to destroy each other the way that many moralistic people would like to see. Instead, these opposites are seen as forces that together complement and enrich what is produced. These sets of actions are seen as unending because the changes that follow will continue to seek further changes, always hopeful that the future will be better.

I have been re-reading about the variety of things that Tan Kah Kee did in his life, from the way he rebuilt his father's failed business to how he tried to accommodate Maoist communism in his devotion to higher education. From what I have read, I see a man of rare wisdom who understood the function of opposites and saw all challenges as positive factors in the changes that everyone has to face. He did not fear contestation or competition but confronted all signs of conflict by using argument and persuasion; he showed a willingness to make sacrifices so that a better outcome would be the final result. Underlying that kind of action was the idea that good and evil could be reconciled, and that the darkness that followed light was not a disaster because light will return. Most of all, I sense in his thinking that the present contains the past: our task is to discern what parts of the past could empower the present, and thereby reject all those parts of the past that hold us back from the progress that the human race hopes for.

You can see how difficult it has been for me to understand Tan Kah Kee's place in history. What I knew about him when I was a boy was later compared to what I learned from Professor Yong Ching Fatt's research. After that, I had to digest what his nephew Tan Kiong Choon showed me in Jimei and Xiamen. And then it was how I saw the World Chinese Entrepreneurs Convention as a project that captured Tan Kah Kee's spirit. I now realize that I have continued to rethink what I can still learn of his exceptional lifework.

This has been something that I have found to be really worthwhile doing and I hope that you do not mind my sharing these stories with you today. I also hope that you will all try to understand this man and discover for yourself what he stands for and give special thought to how he may still have something to teach for all of us.

Prof Wang Gungwu on Singapore history: A tale of separating and connecting (Video and text)