Vibrant, vast and vital: Singapore’s quest for relevance amid China’s evolution

As the book Singapore and China: Neighbours to Friends, Friends to Partners, co-edited by Professor Tommy Koh and Lee Huay Leng, editor-in-chief of SPH’s Chinese Media Group, is launched to mark the 35th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and Singapore, we republish Lee’s introduction titled Impressions. She stresses that Singapore must continually earn its relevance with China through understanding, engagement and adaptability.

My first physical contact with China came in 1990. Prior to that, my understanding of the country was shaped largely by idiomatic tales, historical accounts and literary works.

During the long holiday before my first year at university, my mother and I joined a tour group for a ten-day-or-so journey through Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing and Suzhou. Among all the memories, one that remains especially vivid is my visit to the Xinhua Bookstore on Wangfujing Street in Beijing. Calling it “browsing" doesn’t quite capture the experience — I’ve always had a deep love for reading, and stepping into that bookstore felt more like entering a treasure trove than a shop. I soon realised that there was a significant distance between me and the bookshelves.

Between where I stood and the books on the shelves was a row of lower glass cabinets, behind which stood an expressionless salesperson. If I wanted to flip through any books, I had to ask her to fetch them for me. Since I wasn’t sure if flipping through the books would lead me to buy them, I didn’t dare trouble her.

At 19, I felt somewhat detached from the realities of China, yet the spirited entrepreneurs before me offered a glimpse into a vibrant depth of culture that left a lasting impression.

When we arrived in Suzhou, we spent the evening exploring Shiquan Street. The streetlights cast a soft, dim glow, but the energy of the bustling vendors brought the place to life. The small business owners selling calligraphy, paintings and embroidery greeted us with warmth and enthusiasm. Upon learning we were from Singapore, they eagerly began talking about Mr Lee Kuan Yew. At 19, I felt somewhat detached from the realities of China, yet the spirited entrepreneurs before me offered a glimpse into a vibrant depth of culture that left a lasting impression.

Years later, I learned that in October of that year, Singapore and China officially established diplomatic relations.

Looking back, two vivid images from that trip have stayed with me, each capturing the distinct character of Chinese cities at the time and the contrasting business models emerging amid their economic transformation. Southern cities, in particular, were brimming with energy and entrepreneurial spirit.

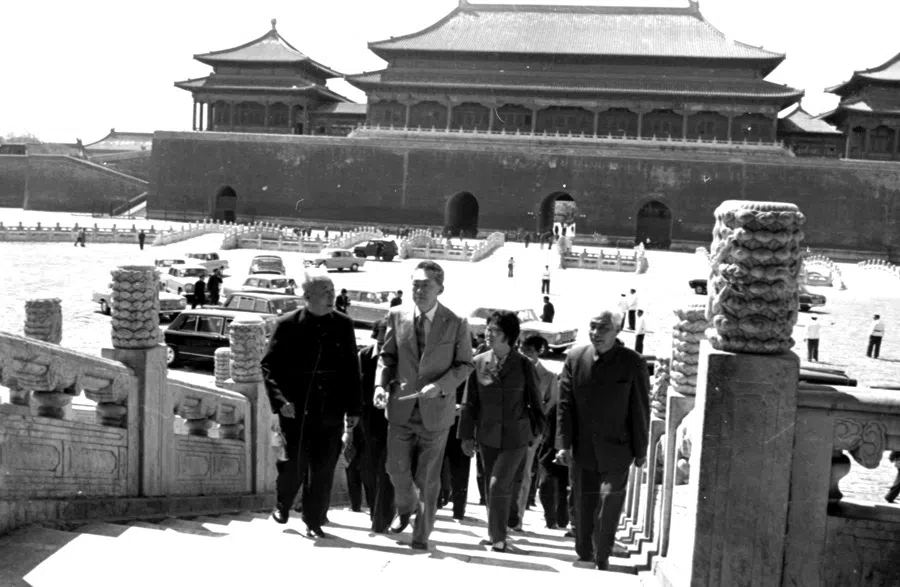

After graduating from university, I returned to China many times, visiting cities across the country. In 1997, I had the privilege of accompanying Founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew on a visit to China and later served as a correspondent in both Hong Kong and Beijing. Even now, I continue to travel to China several times a year. The China I first encountered in 1990 has long since vanished. Last year marked the 30th anniversary of the Suzhou Industrial Park celebration — not just of development, but of transformation. Many of the scenes I once knew now exist only in historical photographs. Yet what we celebrated were the new faces of these old places, and the innovative ideas that reshaped them.

“China” is not a fixed idea — it is vast, multifaceted and constantly evolving. To truly engage with China, we must approach it as a living, shifting reality, one that demands continuous learning and adaptation.

‘China’ is a broad and complex concept

It’s true that China has a long and enduring history, and many aspects of its culture remain deeply rooted. But to assume that it has remained unchanged or stagnant is a serious misconception. Since my posting in Beijing, I have often reminded myself that “China” is not a fixed idea — it is vast, multifaceted and constantly evolving. To truly engage with China, we must approach it as a living, shifting reality, one that demands continuous learning and adaptation.

Without staying current — through reading, observation, and on-the-ground experience — no one can genuinely claim to understand it. The China of today may differ profoundly from the China of even a few years ago. Bridging the past and present, and connecting the dots across time and geography, requires not only curiosity but deep, sustained expertise.

The contributors we invited are Singaporeans who have either worked in China or engaged with it regularly through their professional roles.

In 2023, Professor Tommy Koh invited me to co-edit a book offering Singaporean perspectives on China. As a highly respected senior diplomat and a generous mentor to younger colleagues, Professor Koh’s guidance has always been invaluable. I remain deeply grateful for his trust and encouragement in this meaningful endeavour. I suggested publishing the book on the 35th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Singapore. I also drafted a list of potential contributors, which we discussed and finalised together.

The contributors we invited are Singaporeans who have either worked in China or engaged with it regularly through their professional roles. Their insights, shaped by firsthand experience across diverse fields, offer valuable perspectives that deepen our understanding of the evolving bilateral relationship.

Some essays transport us beyond the 35 years of formal diplomatic ties, tracing a much older and more nuanced history of interaction between Singapore and China, one marked by mutual influence and cultural exchange. Others provide macro-level, analytical reflections on China’s past and present, documenting patterns of cooperation and transformation with thoughtful precision. Still others draw on personal experiences to reflect on the profound transformations unfolding across China.

Singapore needs to stay relevant to China

Singapore and China are an interesting pair of friends. In terms of history, size and population, they are vastly different. However, the relationship between the two countries is not defined by these differences. In fact, for much of modern history, Singapore has played a meaningful role in key moments of China’s development. Over a century ago, figures like Lim Boon Keng — educated under British colonial rule — were already contributing to China’s progress, working alongside Tan Kah Kee to establish Amoy University (Now Xiamen

University) in southern China. Their efforts laid the early foundations for educational reform and cross-cultural collaboration.

Fast forward to the early days of China’s reform and opening up: even before formal diplomatic ties were established, exchanges between Singapore and China were already underway. Chinese delegations visited Singapore on study tours, and people-to-people interactions continued to increase steadily. After diplomatic relations were formalised, these exchanges intensified. Singapore’s hosting of the Asian University Debating Championship, for instance, sparked a nationwide interest in debating across Chinese varsities. Local institutions began offering public administration courses for Chinese officials, and early dialogues between Temasek Holdings and the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) marked the beginning of deeper economic cooperation.

... despite being a small nation, Singapore must consistently demonstrate its value in international relations. To be seen as “useful” is not merely a strategic choice, it is essential.

One of the most iconic milestones is the establishment of the Suzhou Industrial Park, a flagship project aimed at transferring Singapore’s “software” — its governance models, planning expertise and management practices — to support China’s modernisation. Such a close and multifaceted bilateral relationship is rare on the global stage. In many ways, the smaller nation has offered valuable support to the larger one, and at times even served as a model for development.

This mindset reflects a core principle of Singapore’s foreign policy: despite being a small nation, Singapore must consistently demonstrate its value in international relations. To be seen as “useful” is not merely a strategic choice, it is essential. Only by being useful can Singapore remain visible, speak with autonomy and earn respect on the global stage.

During his visits to China, Mr Lee Kuan Yew often posed a critical question to accompanying journalists: “How can Singapore stay relevant to China as it continues its rapid development?” The answer to this question is not fixed; it evolves over time. Whether asked 30 years ago, today, or 20 years from now, it remains a question Singapore must continually ask itself.

This self-awareness is vital. It compels us to keep pace with China’s transformations, to reflect on our own position, and to avoid complacency. Relevance is not a given, it must be earned through understanding, engagement and adaptability.

When I first arrived in Beijing, I lived just two subway stations away from my office. Each day, I walked about 20 minutes to and from work, taking in the scenery along the way. The Starbucks near Fenglian Square was always bustling with people, and under the nearby overpass, street vendors sold pirated books from makeshift stalls.

My route took me along Jishikou Road and Dongzhong Street to Dongsishitiao, with the office tucked behind Poly Plaza. In the evenings, I retraced my steps, passing the same lively scenes — vendors hawking cigarettes and alcohol, and small restaurants spilling light and chatter onto the sidewalks. I remember the roadside always seemed to have a puddle — water or oil, I could never quite tell.

That was only two decades ago.

What will the streets of Beijing look like in another 20 years? What will Beijing be like? What will China look like? When I think of this, I am reminded of the question: How can we stay relevant?

Recently, while staying in Beijing, I found myself walking the same route from my hotel to the Chaoyangmen subway station on a quiet Sunday morning. As I made my way along Dongzhong Street to Jishikou Road, I couldn’t help but wonder if I was on the right path. The streets were relatively quiet, flanked by buildings on both sides, yet something felt subtly out of place — almost as if a familiar rhythm or energy was missing.

Later, I realised it was the absence of the bustling atmosphere. A tuk-tuk was parked by the roadside, and a young chap from a delivery company was charging his phone while eating from his lunchbox.

What will the streets of Beijing look like in another 20 years? What will Beijing be like? What will China look like? When I think of this, I am reminded of the question: How can we stay relevant?

Singapore and China: Neighbours to Friends, Friends to Partners (English and Mandarin version) is available here.