Venezuela exposes the limits of China’s global power

China’s limited response to Venezuela amid Trump’s deployment of naval vessels to the southern Caribbean in the crackdown on drug smugglers makes clear that Beijing cannot (yet) provide an alternative to Washington’s hegemony. Italian commentator Emanuele Scimia discusses the issue.

Logic says that China should worry about the sight of US warships and aircraft in the Taiwan Strait and the China seas regions, not in Caribbean waters and airspace near Venezuela. That is not so. And it is a problem of geopolitical optics for Beijing.

Venezuela risks experiencing its own “Iran moment”, with its Chinese protector likely to condemn in words, but not in deeds, against US military pressure on Nicolás Maduro’s leftist regime. This is just what happened when China vocally condemned US strikes in support of Israeli attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities in June.

The Venezuela crisis is another test for China’s global competition with America.

US President Donald Trump has ordered the deployment of at least eight naval vessels and a submarine in the southern Caribbean, as well as ten F-35 fighter jets in Puerto Rico. The US president apparently made the decision to crack down on drug smugglers, whom he said have links with Maduro.

US assets in the area already sank a boat, killing 17 people who, according to Washington, were part of a Venezuela-based drug cartel. And the Trump administration indicated that US forces had conducted and would launch other strikes of this kind. In turn, Venezuela has deployed military troops and Russian-made fighter jets for military exercises.

A test of China’s influence in the US’s backyard

The Venezuela crisis is another test for China’s global competition with America. The Chinese security and political umbrella has not prevented the US-Israeli bombing of Iran — a key partner of Beijing and component of what many Western observers call the “axis of upheaval” with China, Russia and North Korea — and is proving equally ineffective in the case of Venezuela.

Caracas is a close political partner of Beijing. The Chinese are the Latin American country’s largest creditors, as well as major investors in and buyers of oil and mining products.

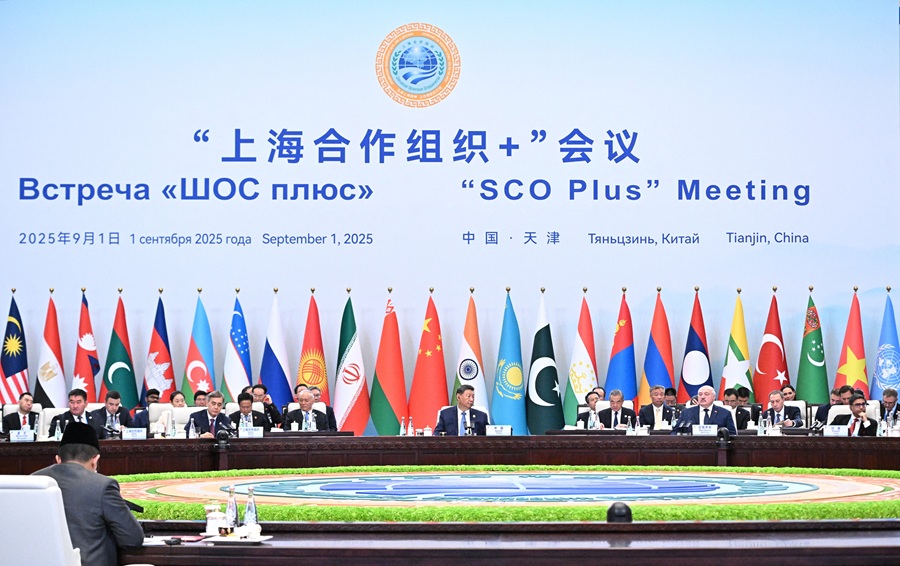

Venezuela has not formally joined multilateral groupings or fora dominated by China, such as the BRICS or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO); however, it actively supports what China promotes in these venues. Simply put, Venezuela is organic to the system of international relations hinging on Chinese power.

Maduro said his country would join Xi Jinping’s “Global Governance Initiative”, which the Chinese president rolled out at the SCO summit in Tianjin on 1 September. Xi’s proposal is, in essence, an attempt to create a new global order that replaces the current one led by the US.

The Chinese paramount leader continues advocating the creation of a new model of international governance prioritising Global South’s countries, such as Venezuela.

But SCO and BRICS summits, or participation in military parades in Beijing, do not offer material protection to China’s friends if they are in Trump’s crosshairs. It is not even a problem of geographical distance.

While Venezuela may be too remote a partner for China to take real actions, Trump demonstrated that distance is no obstacle when, in July, Beijing-friendly Cambodia concluded a truce with Thailand after Trump threatened to halt tariff negotiations with both China’s neighbours if they continued their border conflict.

Sending more weapons to Maduro would not be a realistic option as well.

As in the case of US missile strikes against Iran, the Chinese government publicly condemned Washington’s naval build-up in the South Caribbean as an “interference of external forces in Venezuela’s internal affairs under any pretext”.

China not in a position to offer much support

If the Venezuelan leadership expects direct and tangible Chinese support, and not boilerplate declarations of condemnation, they are likely to remain disappointed.

In reality, Xi has very few implements to influence the current US-Venezuela dynamics. Providing diplomatic cover is a non-starter. It could work to the point when the dispute was confined to rhetorical battles and clash of narratives to shape world public opinion, but not now, when US gunboats and aircraft are in action.

Sending more weapons to Maduro would not be a realistic option as well. Venezuela's defences are so weak relative to US military capabilities that China would have to supply Caracas with an almost unimaginable volume of armaments — advanced anti‑air and anti‑naval missiles and large numbers of drones — merely to create a minimal, effective deterrent against sustained US military action.

China stopped military exports to Venezuela in 2023, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. The resumption of Chinese military supplies to Caracas at scale would face almost insurmountable practical and logistical hurdles due to China’s geographical distance from the theatre of crisis. Not to mention that the US would view it as a military encroachment into the Western hemisphere — Washington’s geopolitical backyard — with risks of escalation amid the current trade and tariff spat between the two great powers.

Iran is a more robust oil supplier to China than Caracas, but even then, Beijing did not openly challenge US raids against the Islamic Republic with the imposition of export controls on rare earths.

US maintains the upper hand

To defend Venezuela in some concrete way, China should actually block or limit the sale of rare earth minerals and magnets to the US, which are crucial for many industrial sectors, including sophisticated weaponry.

Xi has used this trade instrument to temporarily freeze Trump’s tariff threats. But it is highly unlikely that China would resort to such a “bazooka” to rescue Venezuela, straining already tense relations with the US. In fact, Iran is a more robust oil supplier to China than Caracas, but even then, Beijing did not openly challenge US raids against the Islamic Republic with the imposition of export controls on rare earths.

The US does not need to put boots on the ground in Venezuela to instil in China’s Global South partners the idea that Beijing cannot (yet) offer an alternative to Washington’s hegemony. It is sufficient that US forces keep maximum pressure over the Maduro regime with hybrid military-constabulary operations.