Visa-free travel, US tariffs drive Chinese companies to Malaysia

Thanks largely to US President Donald Trump’s tariff onslaught earlier this year, Chinese firms that would have looked to countries like Malaysia as a means to skirt tariffs are now boosting investment in the local market. In particular, Malaysia’s targeted government incentives and deepening ties with Beijing have benefited sectors including semiconductors, electric vehicles and infrastructure.

(By Caixin journalists Zou Xiaotong and Wang Xintong)

On a 4 September Malaysia Airlines flight from Beijing to Kuala Lumpur, every business class seat was taken. The bustling cabin was not an anomaly, rather a scene reflecting the growing business ties between the two Asian nations.

Demand for business-class seats on China-Malaysia routes has been climbing as more Chinese companies explore investment opportunities in the Southeast Asian country, Dersenish Aresandiran, chief commercial officer of airlines at Malaysia Aviation Group Bhd, parent of the national carrier.

The influx is a calculated pivot that is part of a broader shift in global trade, thanks largely to US President Donald Trump’s tariff onslaught earlier this year. Chinese firms that would have looked to countries like Malaysia as a means to skirt tariffs are now boosting investment in the local market. In particular, Malaysia’s targeted government incentives and deepening ties with Beijing have benefited sectors including semiconductors, electric vehicles (EVs) and infrastructure.

This partnership extends from high-level diplomacy to on-the-ground collaboration in trade, investment and travel.

The receipts speak for themselves. In the first half of 2025, Malaysia approved 106.8 billion ringgit (US$25.3 billion) in foreign investment, according to the Malaysian Investment Development Authority. Of that, China contributed 23.4 billion ringgit, up 139% year-on-year and second only to Singapore’s 43.4 billion ringgit. The US accounted for 10.4 billion ringgit.

Visa-free catalyst

Chinese demand for tourism, business and education in Malaysia has boomed recently, said Malaysia Aviation’s Aresandiran, which he believes was driven primarily by the countries’ mutual visa-free policy.

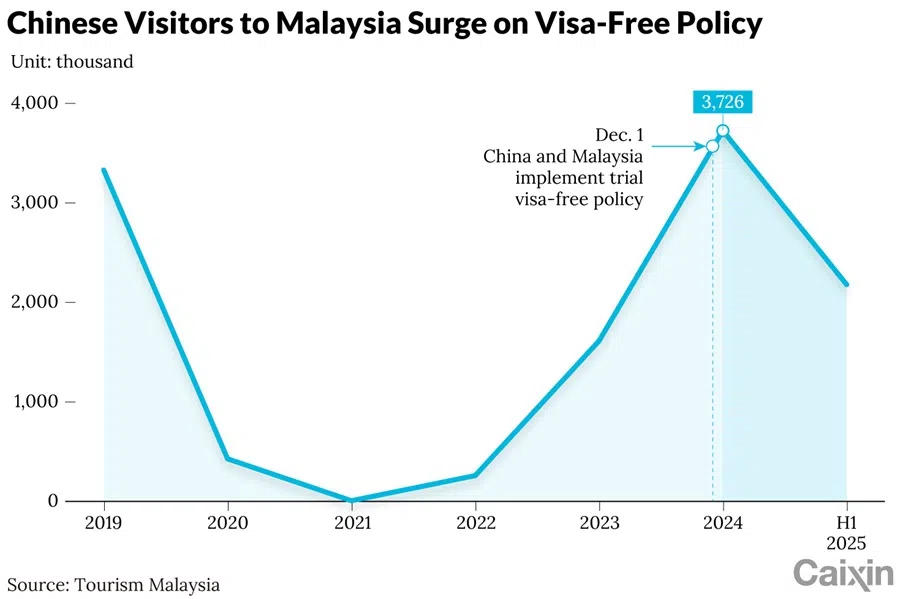

In December 2023, China and Malaysia implemented a trial visa-free policy for their citizens holding ordinary passports. Since then, the number of visitors from China to Malaysia has skyrocketed — more than 3.7 million came in 2024, up 131% year-on-year, according to Tourism Malaysia.

Wang He, general manager of travel service provider Thailand Flying Elephant Travel, told Caixin that since the trial began, his agency’s business-related orders from China in Malaysia have grown by a triple-digit percentage, far outpacing the double-digit growth of tourism bookings.

On a Malaysia Airlines flight, Chinese passengers could be forgiven for thinking they were on a domestic carrier, as attendants are often fluent in Mandarin and Cantonese.

The visa-free policy was made official in July this year. “During the summer, business travellers accounted for 20% to 30% of our total guests in Malaysia,” Wang said. “Many Chinese come on a visa-free entry, exploring the market while on vacation.”

On a Malaysia Airlines flight, Chinese passengers could be forgiven for thinking they were on a domestic carrier, as attendants are often fluent in Mandarin and Cantonese.

From transit hub to production base

Malaysia occupies a prime geographical position at the heart of Southeast Asia, situated between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. This makes it a pivotal hub for key shipping routes and a gateway to other Southeast Asian and global markets.

For a long time, Malaysia served as a key transit point for Chinese companies seeking to reroute goods to circumvent US tariffs. However, that strategy has become less viable after the Trump administration not only raised tariffs on goods from Malaysia but also imposed a 40% additional duty on products being transshipped to avoid tariffs. As a result, many Chinese firms have adjusted their plans.

Very few companies come to Malaysia now for “transshipment”, Wang said, adding that some manufacturers he has worked with have relocated their factories to Malaysia, producing 70% to 80% of their products locally and importing only a small portion of components for final assembly.

“We have hosted Taiwanese clients who previously ran factories in Guangdong and were in the chip business,” Wang said. “After inspecting Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, they ultimately chose Malaysia.”

In May 2024, the Malaysian government launched its National Semiconductor Strategy, committing over 25 billion ringgit in fiscal support — including investment incentives — to transform the country into a global semiconductor hub over the next decade.

“We’re very strong in testing and assembly, but we want to move to advanced packaging. We want to move to IC design,” Tengku Zafrul Aziz, Malaysia’s minister of investment, trade and industry, told Caixin in a September interview. He added that Malaysia has attracted many Chinese, US and European semiconductor companies to invest in those areas thanks to its advantages in talent, infrastructure and supply chains.

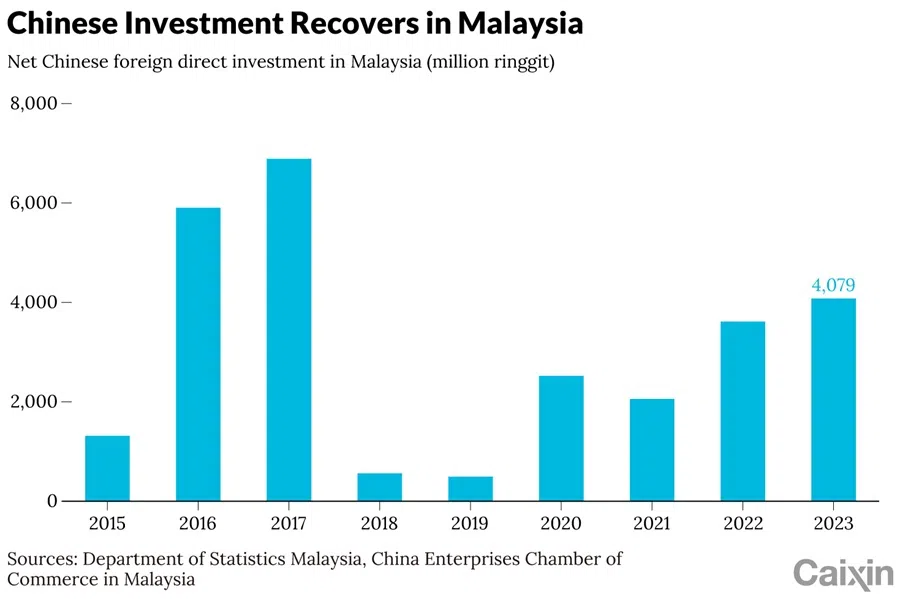

When the Malaysian government changed in 2018 and the [East Coast Rail Link] project was suspended, investment plummeted to 562 million ringgit that year. Following the project’s revival in 2019, Chinese investment began to recover.

Malaysia has also focused on attracting investment from carmakers, medical equipment suppliers and data centre operators because chips are integral to these sectors, said Aziz. Chinese EV giant BYD Co. Ltd. is building a car assembly plant in the country — production is set to begin in the second half of next year.

State investment

One of the most high-profile Chinese investments in Malaysia is a state-backed project: the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL). The 665-kilometre line, which is being built by China Communications Construction Co. Ltd. (CCCC), is a flagship project of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative — a multibillion-dollar infrastructure investment scheme covering Asia, Africa and Europe.

The line will connect Port Klang on the Strait of Malacca with Kota Bharu in the northeast of the country, near its border with Thailand. “In terms of investment scale, the ECRL is the largest single overseas project ever undertaken by a Chinese contractor,” said a source close to CCCC.

Negotiations are underway to extend the ECRL to the Thai border, with results expected soon, the source told Caixin. This could connect the line with the China-Thailand and China-Laos railways, forming a continuous rail link from Malaysia to China.

The project has served as a barometer for Chinese investment. According to a report by the China Enterprises Chamber of Commerce in Malaysia, Chinese direct investment in the country surged to a high of 6.89 billion ringgit in 2017, the year after the project was signed. When the Malaysian government changed in 2018 and the project was suspended, investment plummeted to 562 million ringgit that year. Following the project’s revival in 2019, Chinese investment began to recover.

The project is seen as a major boon for the local economy. Now in the construction phase, it is expected to create 17.6 billion ringgit in job opportunities, the report said. Currently, the project employs about 13,000 workers, 70% of whom are local, Caixin has learned. Over 90% of the equipment and materials for the ECRL are procured locally, the source close to CCCC said.

Sections of the railway are scheduled to open by late 2026 and full operation is expected by early 2028.

Du Zhihang, Yang Min, Liu Peilin and Ding Yi contributed to this story.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “In Depth: Visa-Free Travel, U.S. Tariffs Drive Chinese Companies to Malaysia”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.