Glass towers, German villas and the ghosts of empire: This is Qingdao [Eye on Shandong series]

Once a German colony and now a vibrant Chinese coastal city, Qingdao blends red-roofed European villas with gleaming skyscrapers. Despite its rich history, stunning seascapes and iconic beer, it remains curiously overlooked by foreign visitors. Kennie Ting, author of The Great Port Cities of Asia: In History, gives us the highlights.

(All photographs are courtesy of the author unless otherwise indicated)

The port city of Qingdao (青岛) is situated at the southwestern edge of the Shandong peninsula, along the endless northeastern coasts of the Chinese mainland. For more than a hundred years, the city has played an important role in maritime trade in the Yellow Sea (黄海) region, particularly between China, Japan and Korea, though it has also been a gateway between north China and the rest of the world.

Beloved at home, unknown abroad

While immensely popular with domestic tourists, Qingdao doesn’t appeal to foreign visitors to quite the same degree. This is a pity, for Qingdao is considered one of the most beautiful cities in China, known for its scenic waterfront location as much as for the profusion of historic architecture dating back to the city’s inception as a former German colony.

“China’s most pleasant coastal city with red roofs nestling in green foliage, and the blue sea meeting the azure sky”. These words are attributed to Qing-era writer and political reformer, Kang Youwei (康有为), who lived in Qingdao in his later years and died there. They perfectly capture Qingdao’s place in Chinese popular imagination.

In Kiautschou Bay, with its dramatic landscape of der Wald, die Berge und das Meer (the forest, the mountains and the sea), the Germans found a place that reminded them of home...

The ‘scramble for China’

In 1898, Germany summarily invaded and occupied Jiaozhou Bay (胶州湾), a natural harbour located on the southern side of the Shandong peninsula. The excuse was the killing of two German missionaries by local Chinese. Qing China was powerless to resist. For more than half a century, it had been forced to sign unequal treaties and to concede territory to the Western powers for the establishment of foreign-controlled “treaty ports”.

The Qing government had to concede the area around Kiautschou Bay (as the Germans transliterated it) — including what would become the port city of Qingdao (Tsingtau in German) — on a 99-year lease. With its strategic location at the mouth of the Bay, Qingdao was positioned as the German equivalent of Hong Kong, an economic centre and eastern military hub for the empire.

The Germans invested swiftly and heavily in the city, building up its port facilities from scratch and establishing a naval base. They laid down a railway line that linked Qingdao to the city of Jinan (济南) and thus the Chinese hinterland. These essential pieces of commercial infrastructure would be the foundation for Qingdao’s future success.

In Kiautschou Bay, with its dramatic landscape of der Wald, die Berge und das Meer (the forest, the mountains and the sea), the Germans found a place that reminded them of home; the perfect location for their Musterkolonie, or “model colony”. Mining deeply into their cultural roots, and sparing no cost nor effort, they created the city of Tsingtau both in the image of a familiar village-town in the Black Forest, as well as that of a popular seaside resort.

One of the most impressive monuments in the city is the former Governor’s Residence, perched high up on a hill, and looking like a mix between a hunting lodge and a modest version of Neuschwanstein Castle.

Old Tsingtau

German Tsingtau is located to south and southeast of today’s bustling Chinese metropolis, in the city’s Shinan (市南 district. Zhongshan Road (中山路) (formerly Friedrichstrasse) is its main thoroughfare.

Much of the old town has been painstakingly preserved, researched, documented and restored by the municipal authorities. The visitor today would still invariably be charmed by the quaint and surreal landscape of medieval-ish castles, replete with turrets and verandahs, on every street corner. These housed civic and commercial institutions like the Post Office, or the Seamen’s Guesthouse (Seemanshaus), or the headquarters of the Hamburg-America Line.

One of the most impressive monuments in the city is the former Governor’s Residence, perched high up on a hill, and looking like a mix between a hunting lodge and a modest version of Neuschwanstein Castle. Built in 1903, it is an exemplar of Jugendstil, the German version of Art Nouveau, which originated in the Bavarian city of Munich and was prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Its distinctive look is achieved through the generous use of large and imposing, grey blocks of Qingdao granite in its facade, resulting in an overall aesthetic that is distinctly northern European. That said, the building also contains hybrid elements such as a pagoda-like roof sporting Chinese ceramic tiles, as well as the heads of stylised dragons — a nod to the significance of dragons both in medieval European as well as traditional Chinese culture.

Today’s Badaguan is known for its unique urban design, with eight streets, each named after a historic Chinese pass (e.g. Jiayuguan 嘉峪关), and each lined with a different species of evergreen or flowering tree.

East of the old town lies the Badaguan (八大关), or “Eight Passes” district, the former Villa Quarter built by the Germans. Perched on a cliff overlooking the coast, Badaguan is the quietest and most beautiful area of Qingdao, once home to the many wealthy German and other European magnates in the city, and the magnificent residential mansions they built. Later on would come the Chinese aristocracy fleeing Republican China, and White Russians fleeing Soviet Russia.

Today’s Badaguan is known for its unique urban design, with eight streets, each named after a historic Chinese pass (e.g. Jiayuguan 嘉峪关), and each lined with a different species of evergreen or flowering tree. A walk through this district is a must, for its beautiful tree-lined avenues, for the magnificent views over the harbour and the East China Sea, and for the restoring sea breeze and air. Here too, are some of the city’s prime beaches, playing host to Chinese families picnicking on their mats, as their children shriek and splash about gleefully in the seawater.

A quick jaunt north of Shinan brings us to that other Germanic legacy in the city: the legendary Tsingtao Brewery, famed for China’s most iconic export: Tsingtao beer. Established as the Germania-Brauerei Tsingtao Co. in 1903 to offer an authentic brew to residents of the fledgeling colony, all the brewing apparatus had been imported from Germany, and the beers were brewed here according to regulations set in Bavaria in 1516 governing ingredients that may be used to brew beer.

Today, the brewery still manufactures and exports an astonishingly large volume of Tsingtao Beer to domestic and foreign customers alike. The grounds offer an entertaining albeit kitsch history of beer-making in the city, though this is, by far, the best place for an ice-cold refreshment after a long day’s wandering through the city.

Japanese Qingdao

The Germans held onto Qingdao and the Jiaozhou Bay Concession for only 16 years. In 1914, in the midst of World War I, the Japanese overran the colony. Japan ruled Qingdao till 1945, with an interregnum between 1922-1938, during which it reverted to Chinese rule.

The Japanese would keep much of the German architecture in the Old Town, adapting many of the buildings for their own use. In the meantime, they built their own new city just north of the German Old Town (in today’s Shibei district), adopting the mixed Japanese-European style prevalent in the early 20th century in the home cities and in Japan’s other colonies.

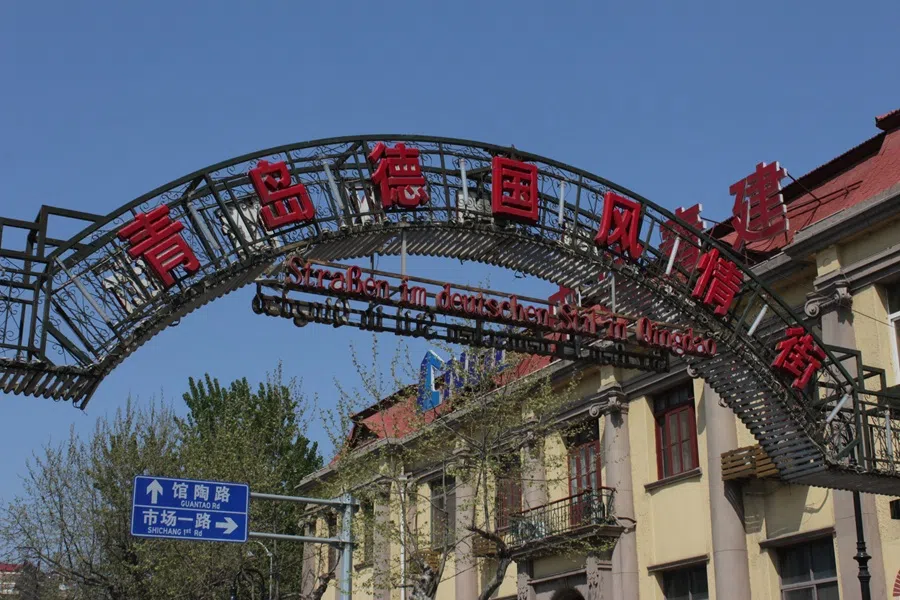

Amongst the historical Japanese-era buildings that have been restored, the most significant is the former Qingdao Stock Exchange, which stands right on Guantao Road, at the heart of the city’s “German Style Street”.

Dozens of monumental buildings were erected along the main street of this new settlement. Many of these structures were local headquarters of major banks and trading corporations like the Chartered Bank of India, China and Australia (today’s Standard Chartered Bank), the Yokohama Specie Bank and the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank.

That main street — and the commercial and financial heart of Japanese Qingdao — is today’s Guantao Road (馆陶路), which extends north from Zhongshan Road. Many of the historic commercial buildings here have been lovingly restored by city authorities, though the whole street is misleadingly touted as a “German Style Street”, perhaps on account of China’s uneasy historical relationship with Japan.

Amongst the historical Japanese-era buildings that have been restored, the most significant is the former Qingdao Stock Exchange, which stands right on Guantao Road, at the heart of the city’s “German Style Street”. Built in the 1920s out of granite and reinforced concrete, this is one of the largest historical buildings in the city, and it looms over the street with its imposing dome and twin turrets, neo-classical columns and Palladian-style pediment.

Elsewhere in the city, the former Japanese Boys’ Middle School building on Yushan Street (渔山街) in Shinan district is another important monument of the Japanese period. At first glance, one would think this a German-era building because of the curved gable and the use of blocks of Qingdao granite in the building’s facade. This is a prime example of the Japanese borrowing German Jugendstil elements in the creation of a completely distinct Japanese-Qingdao architectural style.

Contemporary Qingdao

In the aftermath of China’s “Reform and Opening Up” (改革开放) policy in the 1980s, Qingdao benefited from being one of 14 cities identified as coastal open cities, with large-scale investment going into developing world-class port facilities in the city. It was most recently identified as a key northern node in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Qingdao today is ranked one of the top ten busiest container ports in the world by volume, following close after its sister cities, Shanghai, Ningbo-Zhoushan and Shenzhen. The rewards of economic growth and prosperity can be seen in the glittering skyscrapers that have sprung up all around the edges of the city’s central historic core.

New parts of the old town — such as the historic Chinese commercial quarter, Dabaodao (大鲍岛) — have recently been restored and transformed into food and lifestyle precincts. Meanwhile, in the Shinan district, one frequently spots young couples in their wedding attire, smiling radiantly as they take photos in front of the historic German buildings.

First built in the 1890s as Old Tsingtau’s original landing pier, Zhanqiao (formerly Landungsbrücke), is still an icon of the city today.

One of the best places to take in both the city’s historic and contemporary sides is along the Zhanqiao 栈桥 — the historic pier that extends from the old town’s waterfront into the azure waters of Qingdao Bay (青岛湾).

First built in the 1890s as Old Tsingtau’s original landing pier, Zhanqiao (formerly Landungsbrücke), is still an icon of the city today. The pier culminates in an octagonal pavilion erected in the 1930s, and which is famously used in the logo for Tsingtao Beer, appearing on every single bottle sold in the world.

Walk to somewhere along the pier and look back where you came from. There before you, the historic waterfront continues to stand like it has done for more than a hundred years, with its sturdy brick-and-mortar European edifices and red roof tiles.

To the left of the historic waterfront is a surreal, space-age landscape: a forest of towers fabricated from glass, concrete and steel, standing impossibly tall and glistening in the sunlight.

This is Qingdao, past, present and future.