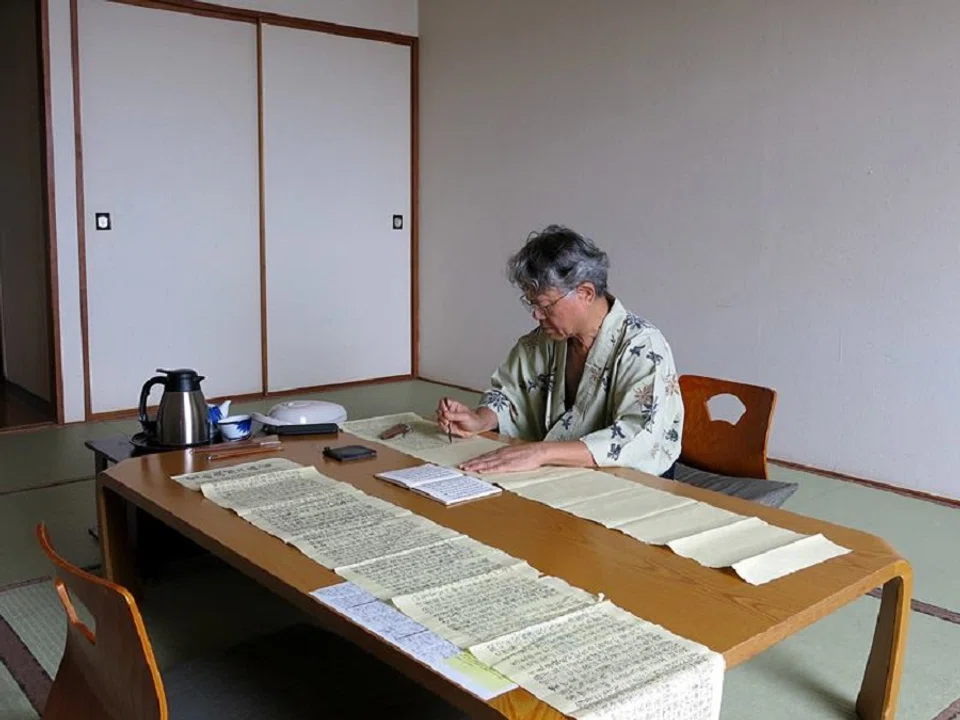

Picking up an ink brush amid the pandemic, what do I write?

Chiang Hsun shares his memories learning calligraphy from his father, and muses that brush strokes on a page are more than beautiful reproductions of text - it is a living art form that, like a play or a film, has the power to move and even heal an audience.

My father wanted all of his six children to learn calligraphy from a young age. When we were five or six, we referred to classics such as Liu Gongquan's Xuan Mi Ta Bei (《玄秘塔碑》), Ouyang Xun's Jiu Cheng Gong (《九成宫》), and Yan Zhenqing's Qin Li Bei (《勤礼碑》). We would grind our ink from scratch instead of using bottled ink, use Lam Sam Yick brand calligraphy brushes - made up of seven parts purple rabbit hair and three parts goat hair - and practise on nine-cell grid calligraphy tracing paper bought from the local stationery store.

I've asked myself my whole life how a cell with the character "one" can have its own imposing presence without seeming hollow or plain.

Later, I realised that this type of word-tracing practice was not unique to my father - almost all Chinese families started with this basic form of education for their children. It was so in Taiwan, Singapore, and Chinese families in Malaysia. Mainland Chinese families did so as well, after reconnecting with this lost tradition following the end of the Cultural Revolution. Such is the widespread popularity of Chinese penmanship training.

Was Father teaching us calligraphy in the true sense of the word?

He often sat behind his children, grabbed their hand, and practised the different strokes with them, a stroke at a time. In these practice sessions, he emphasised the correct posture to have - our feet had to be apart and our wrists and elbows kept off the table. With our fists emptied and palms rounded, only our fingers should maintain a firm grip on the brush.

When it came to education, my father's mantra was to live as an upright and well-disciplined person.

That standardised nine-cell grid is so compact that every Chinese character - from "one" (一 yi) that has only one stroke, to "dragon" (龙 long) that is made up of multiple complex strokes - has to fit within the same-sized cell, and look as comfortable there as every other character on the page. I've asked myself my whole life how a cell with the character "one" can have its own imposing presence without seeming hollow or plain.

Chinese calligraphy can perhaps count as a collective memory of East Asian culture.

The children in Japan also practise Chinese penmanship. Children who are aged three, five, and seven would don traditional costumes and head to the shrines with their parents to learn to write their Chinese names, or blessings like tian chang di jiu (天长地久, forevermore) and shijie heping (世界和平, world peace) with calligraphy brushes.

Chinese calligraphy can perhaps count as a collective memory of East Asian culture.

Countries once influenced by Chinese characters have tried their best to change these characters by using pinyin (拼音) to form new characters in an attempt to rid themselves of the powerful influence of these characters.

It is already the 21st century - nobody uses the calligraphy brush to write anymore. In fact, even the act of writing with fountain and ballpoint pens are gradually replaced by computer typing - the hand no longer writes with a pen. What will happen to calligraphy? What challenges will the unchanging tradition of copying and tracing with calligraphic models face?

She told him that even a dot has to have the power of a rock falling from a mountain peak.

Wang Xizhi, master calligrapher of the Jin dynasty who was revered as the Sage of Calligraphy, had a teacher named Lady Wei. I'm very fond of Lady Wei's "battle strategy of the brush" (笔阵图). Lady Wei taught Wang to dissect a Chinese character into seven elements, starting with the dot (点). She told him that even a dot has to have the power of a rock falling from a mountain peak.

It is no longer just reproducing an image, but recreating the experience of a piece of rock - taking into account its weight, volume, and speed - falling from the highest point of a mountain.

Can calligraphy take off once more via the "battle strategy of the brush"? It is an aesthetic re-definition of calligraphy rather than sticking to the unchanging, stubborn, and old-fashioned ways of copying and tracing.

I'm thankful that I learnt many Tang dynasty regular script (楷书) rules when I was young. Such study has grounded me in the basic principles of calligraphy strokes. Just a thousand years ago, Song dynasty calligraphy rid itself of the technicalities and strictures of Tang dynasty calligraphy, kickstarting a new aesthetic that focuses on individual spirit and self-expression, as spearheaded by Su Shi (苏轼), Huang Tingjian (黄庭坚), Mi Fu (米芾), and Cai Xiang (蔡襄), jointly known as the four greatest calligraphers of the Song dynasty.

I dearly miss Wang Xizhi's masterpieces - especially his Feng Ju Tie (《奉橘帖》), He Ru Tie (《何如帖》), and Ping An Tie (《平安帖》) that are kept in Taipei's National Palace Museum; his Sang Luan Tie (《丧乱帖》) that's kept in Nara, Japan; and his Han Qie Tie (《寒切帖》) that's kept in Tianjin Museum. All of them are letters, letters to his friends, letters with a short message in ancient Chinese "比各佳否" (bige jiafou) or "How have you been?"

Picking up my brush and writing my own words amid the deaths, chaos, and pandemic, I only wish to say in the language of our times: "How have you been? Are you safe and well?"

Related: Taiwan author Chiang Hsun: One humanity, one world | Yuelu: 40 years of longing for a thousand-year-old Chinese academy | A eulogy, intimate memories and a flawed piece of calligraphy | Chiang Hsun: The freed poet in rainy spring, by the Yangtze | Chiang Hsun: How great a mark of rebellion it is to hold an ink brush

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)