[Photo story] Russo-Japanese War: A war fought on Chinese soil and its hard lessons

The Russo-Japanese War was in fact not fought in either Russia or Japan, but in China. It was the culmination of a fierce rivalry between a Eurasian power and an Asian country that showed it could hold its own against a much bigger opponent. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao takes us through a painful period in history that saw many Chinese lives taken.

(All images courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

In the early 20th century, as the Chinese empire weakened, the conflict of interest among the various powers in China intensified, with the biggest tussle between Japan and Russia.

After the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) which was won by Japan ended, there was strategic friction between Japan and Russia in the Korean peninsula and northeast China. These tensions intensified in 1900, when Russia took advantage of the Boxer Rebellion to take control of northeast China, sparking a full-blown land and sea war with Japan. Both sides used the latest weapons and military tactics, including trench warfare, machine guns, and observation balloons. The Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), which Japan also won, was practically an exercise in preparation for World War I, which is why it is also known as "World War Zero".

An example of Asian supremacy over a major power

The Russo-Japanese War had a major impact on China. It happened on Chinese soil, but China was powerless to prevent it and suffered great human losses. Such a reality added to its people's sense of humiliation. On the other hand, the fact that a small Asian country could defeat a major power like Russia was encouraging for the Chinese. Especially since China's intellectuals well knew that Japan's success lay not just with a modern army, but with organising and preparing a people for modern politics, military, economy, and social culture, all of which China had much to catch up with. And so, after the Russo-Japanese War, with the unprecedented reform of the Qing empire and heightened activity among Chinese revolutionaries, there appeared to be great potential for the revival of a weakened China.

The Liaodong peninsula was ceded to Japan during the First Sino-Japanese War through the Treaty of Shimonoseki, made final in April 1895. But protests by Russia, France and Germany forced the Japanese to relinquish the claim to Liaodong in exchange for an additional indemnity of 30 million taels from China, while all the other stipulations of the treaty remained. Russian Foreign Minister Alexey Lobanov-Rostovsky and the Chinese viceroy Li Hongzhang further signed the Sino-Russian Secret Treaty (or the Li-Lobanov Treaty) in June 1896, which allowed Russia to build the Chinese Eastern Railway through Heilongjiang and Jilin, in the name of fighting Japan together.

After the First Sino-Japanese War, while Japan managed to end Korea's status as a satellite state of China, it did not end Russia's special privileges in Korea, but ended up signing an agreement with Russia.

In 1897, after the German Navy entered Jiaozhou Bay, Russia also openly deployed its navy to Lüshun and Dalian, purportedly to help the Qing court to defend its land. Subsequently, it forced the Qing court to sign the Convention for the Lease of the Liaotung Peninsula, or the Pavlov Agreement, in 1898. The Russian Navy then heavily invested in building the port at Lüshun into Port Arthur, as a major base for its Pacific fleet. When the Boxer Rebellion broke out in 1900, Russia took the opportunity to seize Manchuria. At the same time, there was an intriguing shift in the international situation, with the various powers supporting Japan for their own interests. The turnabout gave the Japanese much confidence in going to war with Russia.

At dawn on 4 February 1904, Emperor Meiji summoned Prince Itō Hirobumi, who was then president of the Privy Council, to discuss the pros and cons of going to war. Prince Itō analysed the situation and felt that the conditions were advantageous for Japan, while Russia faced domestic political instability and an ill-prepared military. This confirmed the Emperor's resolve in going to war against Russia.

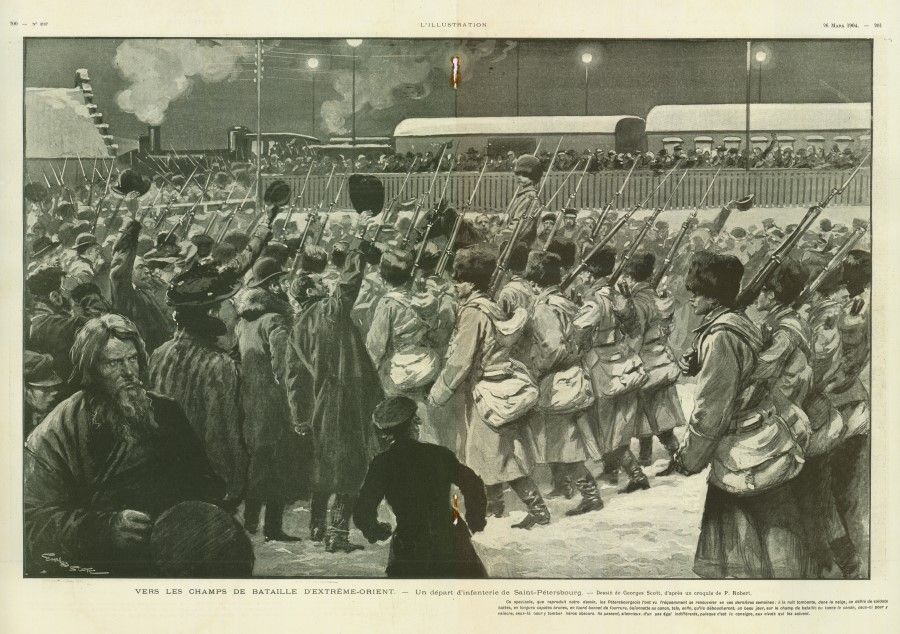

Before the war, Japan had executed its ten-year plan for building its military and diplomacy. It deployed many spies to gather intelligence and issued 100 million yen worth of war bonds. It also announced several decrees relating to wartime military spending, as well as organisation and planning. From late 1903, military supplies were sent to Incheon in Korea. All was ready. Japan and Russia each conducted a nationwide mobilisation: tens of thousands of young men from the west crossed the rolling plains, while those from the east traversed the seas to take up new lethal weapons, and faced off against one another in a land that was foreign to both sides.

On 5 February 1904, commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet Marshal-Admiral the Marquis Tōgō Heihachirō received a secret order and understood that the government had decided to protect its interests in Manchuria and Korea. The order itself was simple: destroy the Russian fleet in the East China Sea. In order to gain control of the sea and cover the landing battle, the Combined Fleet launched a series of attacks on Port Arthur. In early May, to cover the landing of Japanese troops on the Yalu River, the Japanese launched a third attempt at blocking Port Arthur, successfully restricting the movement of the Russian Navy, but at great cost.

At 1.49pm on 27 May 1905, the ultimate battle between the Japanese and Russian navies took place in the Tsushima Strait. Both sides sounded the call to arms at practically the same time. To seize the opportunity to attack, Admiral Tōgō had his fleet execute a turn in sequence, essentially a U-turn on the spot. The flagship that he was on took heavy Russian fire, but it bought the crucial 15 minutes necessary for the Japanese to move into formation.

And when the Japanese troops did get in position, the figurative tide turned in an instant. 24 hours after the start of the battle, 22 Russian ships had been sunk, seven captured, and six detained after escaping to neutral ports, with 5,000 human casualties and 6,142 taken prisoner. By contrast, the Japanese lost three torpedo boats, with 700 killed or wounded. This day marked the end of the fleet of the Russian Empire, and was commemorated in Japan as Navy Anniversary Day from 1906 to 1945, in honour of this victory.

On land, however, the Japanese suffered heavier losses. The Japanese Third Army, led by General Nogi Maresuke, was prepared to attack Port Arthur. By July 1904, they had captured key locations surrounding Port Arthur, which was protected against Japanese bombardments by 19 kilometres of fortifications and concrete-and-steel batteries that dominated the rugged, hilly terrain, along with some 350 powerful cannons.

The Japanese launched numerous attacks, and on 2 January 1905, Lieutenant General Anatoly Stessel surrendered to Nogi. Port Arthur was lost. Japan mobilised a total of 130,000 troops in this battle; 15,400 were killed and 44,000 injured.

After Port Arthur fell, the land battle turned towards the Russian command centre in the Far East: Mukden. At this point, the Russians had 380,000 soldiers, 28,000 cavalry, 30,000 grenadiers, and 1,300 cannons, while the Japanese had 200,000 soldiers, 150,000 grenadiers, engineers, and assorted troops, and 1,100 cannons. This final battle began in late February 1905, along a front stretching over 100 kilometres. After about 20 days of fighting, the morale of the Russian troops flagged and they broke through to retreat to Harbin. Both sides mobilised nearly 600,000 troops, with over 40,000 casualties for the Japanese and 90,000 for the Russians. The Japanese won this battle that ended the war on land.

Battle between Japan and Russia but an awakening for China

After the Battle of Mukden, Japan and Russia were under pressure to engage in peace talks. Japan's finances were in bad shape, and it was unable to afford the costs of conscription and military supplies. On Russia's part, it had the edge in terms of troop strength, but domestic revolution and unrest had broken out since its defeat at Port Arthur. As for the other powers, ending the war would also be good.

On 5 September 1905, the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. In the treaty, Russia acknowledged Japan's rights of "guidance, protection and control" over Korea, turned over the lease of the Liaodong peninsula and the rights to the South Manchuria Railway to Japan, ceded to Japan the southern part of Sakhalin Island, and acknowledged Japan's fishing rights along the coasts of Russian possessions in the Far East. The Japanese and Russian governments each ratified the treaty on 10 and 14 October 1905, and the documents were exchanged on 25 October in Washington, officially ending the Russo-Japanese War.

However, the benefits exchanged between Japan and Russia were in fact the blood and tears of the Chinese people. Although this war was between Japan and Russia, it was fought in northeast China, over special privileges in that region and in Korea. Many Chinese people in the northeast were killed or injured and made homeless amid the fighting. Their country and their homes were destroyed, and they knew only too well the helpless feeling of their lives being at the mercy of others.

But while China's status hit rock bottom with this war, there was a general awakening among China's intellectuals. There was a deep sense that China had a lot to improve on in its politics, military, economy, society, as well as education and culture, in order to modernise. The old system and old way of thinking were crumbling; change and revolution became the driving force of China's progress. The tide of history was not to be reversed, as the land took on a new vitality.

Over a century later, the Russo-Japanese War remains painful for the Chinese. Especially with the current complexities in Northeast Asia, such historical wounds are a constant reminder to the people of China that staying united and building up the country and its people is the only way to avoid getting bullied and maintain world peace.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)