[Photo story] The first decade of 'new China': In the name of idealism

The first ten years of "new China" as established by the Chinese Communist Party were a time of initial progress and improvement, only to be followed by the problems of communism. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao gives us a look into the idealism and difficulties of the time.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao, except otherwise stated.)

After the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) established the People's Republic of China (PRC), it entered a phase of large-scale and long-term economic construction.

Unlike most countries, the CCP was a revolutionary party guided by Marxist philosophy, with Leninism as its political system, and the Soviet Union's planned economy as its primary learning model. Essentially, it was another path of human social system experimentation against Western capitalist market economies.

In the first decade after its establishment, by taking guidance and assistance in industrial technology from the Soviet Union and following its development model, the PRC repeated the Soviet Union's path of development. Initially, there was rapid progress in national economic construction, but in the second decade, there was stagnation, waste, regression, scarcity in daily life, and even tragic famine.

Establishing unquestionable authority

In 1953, the newly established PRC, just out of the Korean War, began implementing its first Five-Year Plan, channelling massive investments into heavy industry and infrastructure. Concurrently, it integrated private industries and traditional handicrafts into the national economic planning system.

It must be noted that there are two tenets of Marxism: the first is the theory of stages of struggle, whereby the proletariat overthrow the rule of the bourgeoisie through violent revolution to establish proletarian dictatorship. The second is the abolition of private ownership, as Marxism believes that various forms of exploitation, oppression and greed stem from private ownership, it must hence be eliminated to establish comprehensive public ownership, thereby liberating individual freedom and productivity.

The ultimate realisation of these two tenets represents the establishment of a communist society where everyone is wealthy, equal and happy, an ultimate paradise on earth.

Only by understanding the almost religious fervour of classical Marxism and Bolshevism and the faith goals pursued at all costs can one understand what happened after the birth of communist China.

The three years or so of civil war between the Kuomintang (KMT) and CCP had led to massive loss of life and property, so the three years from 1949 to 1952 were a period of economic recovery for mainland China, primarily focused on rebuilding social order and restoring normal economic operations.

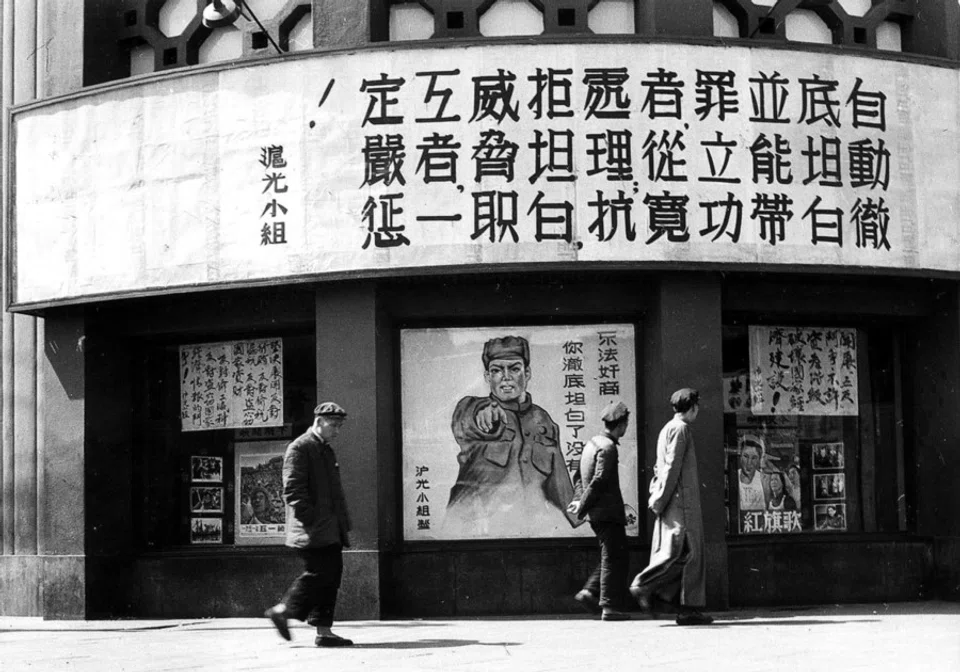

However, in pursuit of the revolutionary goal of communism, the CCP government took a hardline approach at the outset to establish unquestionable authority, thoroughly eliminating remaining hostile KMT forces and various "counter-revolutionaries".

The three years of the Korean War did not weaken communist China. On the contrary, it enabled the CCP government to establish political authority, mobilise the people in patriotism and transform society through directives. In addition to fighting in the Korean peninsula as a volunteer army, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) also settled by force the last remaining anti-communist guerrillas and long-existing local armed groups in the vast mountains and forests of the southeast coast and southwest.

Land reform teams were also sent to rural areas nationwide to hold struggle sessions (or denunciation rallies) against landlords and distribute land and property to tenant farmers. Landlord families were driven out of their homes, and there were many instances of extreme violence against them.

Residents were also subject to "class differentiation", with a division between the "five red categories" (peasants, workers, PLA revolutionary soldiers, CCP revolutionary cadres and revolutionary martyrs) and the "five black categories" (landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, bad influences or "bad elements", and right-wingers). The former enjoyed political trust, as well as privileges such as rationing, education and promotion, while the latter were treated as outcasts, strictly supervised and deprived of various rights, and were constantly the target of criticism in political struggles.

As for urban areas, the government forcibly closed brothels, offering therapy for sex workers to transition to other jobs, while also vigorously cracking down on hooligans and gang members.

In the business sector, the government initiated the "Three Anti" campaign (against corruption, waste and bureaucratism) and "Five Anti" campaign (against bribery, theft of state property, tax evasion, cheating on government contracts and stealing state economic intelligence). Business owners were required to submit self-reviews to ensure that they were not engaging in commercial fraud.

The first Five-Year Plan

Since all resources were controlled by the government and trade unions were dominated by the CCP, businesses had no choice but to be fully compliant. And while the measures were harshly implemented and seemed cruel and ruthless, objectively, it did quickly establish stability in China, out of the chaos and devastation after the civil war.

Farmers who gained land ownership worked actively, and agricultural production significantly increased. Urban business owners dared not engage in speculation, leading to improvements in both the national economy and social order.

As for the people's mental state, it was reminiscent of the immense revolutionary fervour in human history, with the masses chanting righteous slogans, waving battle flags, and brimming with unparalleled revolutionary passion, disregarding the many lives crushed by the revolutionary upheaval, including countless innocent victims caught in the crossfire, as well as the sceptics trembling in dark corners. Most people were satisfied that China could finally resist the powerful foreign imperialist armies, and society was vibrant and inspired, marching towards a bright future.

Given the favourable domestic and external environments, the government's first Five-Year Plan was also a movement for "socialist transformation", namely, the implementation of Marxist theory of public ownership. This plan included "agricultural socialist transformation", "artisan socialist transformation" and "capitalist industrial and commercial socialist transformation", with the aim of nationalising all land and private enterprises nationwide.

This was done by issuing stocks to farmers and private entrepreneurs in the name of "public-private partnership" as a means of nationalisation, with the value of these stocks set at low prices by the government. Consequently, the land previously allocated to farmers by the government was reclaimed.

Business owners organised parades, celebrating the socialist transformation movement of public-private partnership with great fanfare. Time-honoured shops, companies, restaurants, theatres, dance halls, amusement parks and performing groups of all sizes in Beijing, Shanghai and bustling urban streets nationwide became state-owned enterprises overnight.

Furthermore, to ensure that this nationwide transformation movement would not be sabotaged or hindered in any way, in January 1954, Mao Zedong personally led the "suppression of counter-revolutionaries" movement. The goal was to thoroughly investigate and suppress former KMT party, government, military and police officials, as well as administrative, educational and cultural officials at all levels of local government from the previous Nationalist era, along with traditional religious figures who opposed communism, all of whom were convicted as "counter-revolutionaries".

Strong dissatisfaction from supporters

During the civil war between the KMT and CCP, in order to reduce the KMT's resistance force, the CCP adopted a lenient policy towards lower-level officials. However, over four years after the establishment of the communist government, Mao Zedong decided to settle scores with former KMT members nationwide.

According to reports from the Public Security Bureau at the time, the movement led to the arrest of more than 2.62 million people, among whom over 712,000 were executed as "counter-revolutionaries", over 1.29 million were imprisoned, over 1.2 million were placed under control at various times, and more than 380,000 were arrested and subsequently released after being deemed to have committed minor offences and were then rehabilitated through ideological transformation. It can be said that the old forces of the KMT were thoroughly wiped out, both physically and spiritually.

With these swift and decisive measures, the first Five-Year Plan, in conjunction with the socialist transformation, transformed China from a traditional society with loose governance and individual autonomy into a by-the-book, highly organised military-style society. For China with its lagging economic development and low levels of education, the planned mobilisation of personnel and resources brought about immediate progress. Industrial and agricultural production soared, even up to 200 to 300 times.

What started as simple criticism of bureaucratic tendencies quickly escalated into a rejection of the CCP's authoritarianism.

This led to two extreme outcomes. First, many liberal intellectuals who had previously supported the CCP and believed in its democratic promises became strongly dissatisfied, seeing that the party was now omnipotent and personal freedom no longer existed. Second, the success of the first Five-Year Plan inspired Mao Zedong's ambition, leading him to implement more radical policies, pushing China to "become a communist society at a run". The collision between these two forces quickly led to a tragic outcome for both.

In the spring of 1957, Mao Zedong proposed encouraging non-party members to criticise the CCP, to help rectify bureaucratic and sectarian tendencies within the party. Mao proposed the policy of "Let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred schools of thought contend"; he summoned and met with prominent intellectuals, asking them to "say whatever they knew and not to hold back; those who spoke would not offend, and those who heard should take heed".

However, this encouragement to criticise the CCP eventually evolved into a political storm. Liberal intellectuals who had stood with the CCP against the KMT during the Chinese Civil War now took the opportunity to express their strong dissatisfaction with the CCP.

They wrote critical articles in newspapers and gave speeches at mass gatherings opposing the CCP's dictatorship. Their rhetoric became increasingly fervent, including demands for the CCP to withdraw from government institutions and schools, to end one-party rule, and even advocating for a rotation of power between the CCP and other democratic parties. What started as simple criticism of bureaucratic tendencies quickly escalated into a rejection of the CCP's authoritarianism.

The Great Leap Forward

The criticism grew louder, causing shockwaves among Mao Zedong and the top echelons of the CCP, who felt that the CCP regime was facing an unprecedented crisis. By summer, Mao Zedong launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign in a political counterattack, claiming that the earlier encouragement to criticise the CCP was to "lure the snakes out of their holes", to expose the true faces of the opponents and effectively strike them down.

The Anti-Rightist Campaign silenced intellectuals nationwide, and Mao Zedong no longer heard any dissenting voices, inside or outside the party. Policies became increasingly unrestrained and divorced from reality.

Public opinion abruptly shifted 180 degrees. The intellectuals who were initially encouraged to speak out against the CCP were now openly criticised, including most who still sincerely supported the CCP but wished for some improvements in its practices. Most of them had been deliberately encouraged to speak up but were now labelled as "rightists".

In the end, more than 500,000 "rightists" nationwide were sent to work in factories and rural areas for reform through labour. Many worked all day, malnourished and exhausted, and eventually went to their eternal rest in remote forests and snowy areas, with their families only learning the truth years later.

The Anti-Rightist Campaign silenced intellectuals nationwide, and Mao Zedong no longer heard any dissenting voices, inside or outside the party. Policies became increasingly unrestrained and divorced from reality.

The second Five-Year Plan

The second Five-Year Plan implemented in 1958, also known as the Great Leap Forward, focused on significantly increasing heavy industry and agricultural construction, promoting nationwide steel production and intensive crop cultivation to increase food production. Mao's goal was to "surpass Britain and catch up with America".

At the same time, "people's communes" were established in rural areas, as an era where "meals cost nothing" had begun. This communist utopian society, enforced through absolute power, led to unprecedented disasters in Chinese history.

Blast furnaces sprang up all over the country, with people abandoning their work to contribute their pots, shovels, hammers, nails or any iron objects they could find for smelting. They worked day and night, while the party's propaganda machine proclaimed constant breakthroughs in steel production.

As for food production, newspapers published a famous photo of rice fields so dense that even young girls could sit on them. Reports of bumper rice harvests came from all over the country, with quantities going up to absurd levels. This propaganda success delighted Chairman Mao, who even worried about "having too much food to eat".

However, the reality was quite the opposite. Due to the lack of modern steelmaking equipment and professional standards, the "backyard steelmaking" operations produced useless scrap steel, wasting vast amounts of labour and resources.

The so-called intensive rice planting technique was also unscientific, entirely fabricated by agricultural officials to comply with directives from the higher ups. In fact, amid a waste of resources due to policy, farmers' productivity significantly declined, leading to a sharp drop in grain production.

Many rural areas experienced famine, but local officials reported false news of abundant harvests and farmers' satisfaction. No one dared to tell the truth because everyone had seen the fate of those who did.

Strict control of population movement and information

Only General Peng Dehuai, who had protected Mao Zedong's life in northern Shaanxi during the civil war and was trusted by Mao, ultimately decided that he could not stand to see innocent people starve to death. In July 1959, he presented a lengthy document at an expanded meeting of the Central Political Bureau, bluntly stating that the Great Leap Forward was reckless and full of exaggeration, leading to the difficulties of the time. He blamed "leftist subjectivism" and "enthusiasm of the petty bourgeoisie" as the root of the problem and asserted that "political leadership cannot take the place of economic laws".

While Peng's language was mild and tactful, Mao Zedong saw it as a blatant challenge to his leadership authority. He immediately launched a political counterattack, labelling Peng and several party adherents as the "anti-party group", stripping them of all their duties and relegating them to the lowest levels to eventually be dealt with.

At the same time, to demonstrate Mao's unquestionable correctness, the Great Leap Forward was intensified, and the tragic famine in rural areas expanded nationwide. However, due to strict control of population movement and information, unlike the great famines in Chinese history, this time starving farmers could not get out and find food elsewhere, and could only stay where they were and die of hunger. As for city dwellers, all they knew was that their food rations were short; they did not know of the starvation in the rural villages, much less about offering assistance.

The truth about the Great Chinese Famine was also unknown to the world until May 1962, when tens of thousands of starving people from rural Guangdong tried to cross the border into Hong Kong, shocking the international community and drawing global attention to the famine. As the severity of the disaster shook the ideological beliefs of the CCP leadership, at the beginning of that year's party conference, Mao Zedong engaged in self-criticism, taking a step back with State Chairman Liu Shaoqi taking over.

Liu corrected the ultra-leftist policies, allowing small-scale private economies in rural areas, while reducing unnecessary input - only then did the famine gradually ease.

In the decades that followed, estimates of the death toll from the famine ranged from 15 million to 55 million, based on statistics released by the Chinese government at different times and the research of foreign academics.

In practice, abolishing private property did not get rid of human selfishness; instead, they shamelessly wasted public resources and became lazy idlers.

Success from a low starting point

Looking at the first decade of communist China, Mao Zedong devoutly followed Marxism, Lenin's organisation, and Stalin's models of political and economic construction, to create an unprecedented "new China" - a perfect communist society realised in China.

The methods were harsh, but they did indeed swiftly pull China out of the chaos, poverty and famine of civil war in the initial years. Farmers' lives stabilised, urban crime was resolved, and people's lives were more peaceful.

While industrialists and business owners were intimidated, and the party and government propaganda machine began to vilify "capitalists", in impoverished China, the proportion of industrial and commercial workers was negligible, and mainstream public opinion remained unaffected.

However, after all land and businesses, large and small, were nationalised, Marx's theory that "abolishing private property will eliminate selfishness and greed" was immediately put to the test.

In practice, abolishing private property did not get rid of human selfishness; instead, they shamelessly wasted public resources and became lazy idlers.

As for the generation that grew up after 1949, indoctrinated with Mao's ideology in a closed environment, they were gradually groomed into loyal soldiers of Chairman Mao...

The success of the first Five-Year Plan was largely due to China's low starting point, military-style resource allocation, and focus on heavy industry and infrastructure construction, which yielded immediate results, like how the first Five-Year Plan succeeded in the Soviet Union. However, Mao Zedong, eager to realise his communist utopian blueprint, pushed forward with the unscientific Great Leap Forward, resulting in the most tragic peacetime famine in Chinese history.

Another key reason that extreme ideology was implemented without resistance was the absence of any form of checks and balances on power. Initially, Mao Zedong purged the former KMT party, government and military officials, as well as rural administrators. He then cracked down on intellectuals who had previously supported the communist revolution but now expressed dissenting opinions about communist policies, leaving them physically and mentally devastated and silenced. Having lived through different times and experienced different governments, with reality as a reference, they quickly woke up from their dream.

As for the generation that grew up after 1949, indoctrinated with Mao's ideology in a closed environment, they were gradually groomed into loyal soldiers of Chairman Mao, ready to accept any directives from him and mercilessly attack anyone who criticised him.

And when there were no more enemies or dissenters outside the party, Mao's struggle turned towards the revolutionary comrades within the CCP; the first casualties were longtime comrades such as Peng Dehuai. However, this was just a prelude to the storm of the CCP's internal struggle, which erupted in the Cultural Revolution of 1966.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)