[Photo story] The Cultural Revolution: A Taiwanese reflects

In Chinese history, the Cultural Revolution was a period of major impact. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao gives us a glimpse into the tumultuous period.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao)

In December 1978, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) held the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee, criticising extreme leftist dogmatism and proposing “emancipating the mind”. This implied that thinking had been previously constrained. The meeting is regarded as a milestone: Deng Xiaoping was shifting away from Mao Zedong’s policies.

The year 1978 was also designated as the “First Year of Reform”, and since then, the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee has become synonymous with a historical turning point.

This shift did not happen by chance, but was filled with intense intra-party power struggles and ideological battles. For nearly 30 years, Chairman Mao Zedong had been deified as a political leader, and his words and policies were treated as unquestionable truths, like religious edicts. Even after his death, altering his directives was seen as blasphemous, subject to the condemnation of his followers.

However, the fact is that Deng Xiaoping boldly implemented changes and gained widespread support from the people, who were exhausted by the endless political campaigning and no longer wanted to shout battle slogans. Instead, they wished for a peaceful life, focusing on work and improving their families’ and their own lives. A popular saying at the time was: “After 30 years of hard work, overnight we are back to where we started before liberation.”

The insecure leader Mao Zedong

In 1962, after Mao Zedong admitted to his mistakes during the Great Leap Forward and took a step back, pragmatic party leaders Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping took charge. They allowed some freedom in rural production and sales, which gradually alleviated the famine crisis and restored the national economy to normalcy.

However, beneath the calm surface, a larger political storm was brewing. Mao believed that the perfection of the communist revolution was being corroded by revisionism, and internal party evaluations were beginning to target him and challenge his absolute authority. Worse still, the changes in China were very likely influenced by Soviet revisionism, posing a serious threat to China’s socialist revolutionary path and Mao’s leadership.

After Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev took over and began to significantly alter the Stalin-era policies. He rehabilitated a large number of political prisoners, relaxed political and economic controls, and shocked the world by directly criticising Stalin for implementing a reign of terror, harming loyal cadres and promoting a cult of personality.

Mao ended ties with Khrushchev, leading to a rapid deterioration of Sino-Soviet relations.

Since Mao’s new China was modelled after Stalin’s Soviet Union, Khrushchev’s revisionism alerted Mao to the potential fate of both his new China and himself. Although later suppressed by Soviet troops, the 1956 Hungarian uprising against communist rule had already shaken the communist world. Mao became convinced that Khrushchev’s compromising revisionism encouraged bourgeois restoration, and he decided to launch a comprehensive counterattack, both domestically and internationally.

In a country where ideology dictated every aspect of life, the political counterattack would first focus on central thoughts and theoretical formation, then expand into widespread media criticism and propaganda. This moral domination of the opponent would pave the way for their eventual physical downfall, representing the final victory.

Despite temporarily stepping back to a secondary role in the work of the central government, Mao always maintained a firm grip on the party organisation and the military, ensuring his power and will were executed.

Mao asserted that even under the dictatorship of the proletariat and after the socialist transformation, new bourgeois enemies would still arise, including within the Communist Party, and so it was necessary to continually emphasise the class struggle.

Between 1963 and 1964, the CCP Central Committee published nine open critiques of the Soviet Union, accusing Khrushchev of usurping the power of the Soviet party and state, and claiming that the Soviet Union was facing an unprecedented crisis of capitalist restoration. Finally, Mao ended ties with Khrushchev, leading to a rapid deterioration of Sino-Soviet relations.

Mao believed that the struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie would persist for a long time, and thus he proposed the theory of “continuous revolution”.

Mao’s war dance

Once the ironclad ideological theory was established, Mao Zedong turned his critical attention to articles written by intellectuals. He instructed several writers from the Shanghai Municipal Propaganda Department to write critical articles in newspapers, accusing certain intellectuals of using ancient Chinese stories to criticise Mao’s policies and sympathise with those opposed to him.

Mao believed that the struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie would persist for a long time, and thus he proposed the theory of “continuous revolution”. By this point, the direction of public opinion nationwide was becoming increasingly evident — a new political movement was on the horizon, but it seemed that only Mao knew the scope, nature and targets of this movement.

In May 1966, during an expanded meeting of the Central Politburo, Mao Zedong proposed that the “capitalist roaders” within the party had infiltrated the academic, media, literary and publishing circles, and therefore, it was necessary to seize control of these fields. The meeting also decided to establish the “Central Group of the Cultural Revolution”, and the “May 16 Notice” issued by the meeting marked the official start of the Cultural Revolution.

Soon, the party cadres responsible for central propaganda were replaced. Several Peking University professors posted big-character posters openly criticising the Beijing Municipal Committee; Mao Zedong publicly praised this and ordered all newspapers to reprint them.

Those appointed by Mao took control of the main newspaper media and deliberately incited rebellious sentiments among young students nationwide. The first group of “Red Guards” formed by rebellious students emerged in Beijing.

At this time, Liu Shaoqi, who was overseeing the work of the central government, sent work teams to schools. Ostensibly, these teams were to carry out the tasks of the Cultural Revolution, but in reality, they aimed to calm the situation, hoping students would maintain regular classes and not cause too much trouble.

Here, it is necessary to briefly explain the mindset of the leading CCP cadres from the central government to the local levels. When they first joined the Communist revolution, they were all passionate youths full of ideals. They witnessed various forms of darkness and injustice in society: bureaucrats using power for personal gain, amassing wealth, oppressing the common people, imperialist forces seizing everything, and the masses navigating between life and death.

Men endured hard labour, women sold their bodies, and yet they could not make ends meet. So, they resolutely joined the revolution, risking lives and spilling blood in the pursuit of a wealthy and equal society.

After the new China was founded, they struggled against landlords, targeted the remnants of past enemies, eliminated private ownership, and even criticised intellectuals who held dissenting opinions. Through all the cruelty, they always supported Mao Zedong. After all, Chairman Mao had led them through several severe internal splits, but in the end always made the correct decisions, reuniting the revolutionary forces, enduring the arduous war of resistance and the bloody civil war, and achieving final victory in the revolution.

Targeting high-level cadres

After the birth of the new China, Mao continued to suppress “counter-revolutionaries”, “reactionaries” and “bourgeois enemies” to establish a communist society, which was believed to be necessary to defend the revolutionary regime. Even the “Anti-Rightist Campaign” was overseen by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.

However, the Great Leap Forward, which resulted in a massive famine in the countryside and widespread starvation, shook their once unwavering beliefs. The vast majority of peasants, who were the foundational support of the CCP’s revolution, provided food, labour and intelligence; they were one with the communist revolution. Now, not only did they not have the prosperous life they were promised, but they also starved to death during the peaceful years following the revolution.

Furthermore, General Peng Dehuai, who had long been loyal to Chairman Mao, was deemed a major criminal and labelled as part of an “anti-party clique” for subtly speaking truths. The tragic situation of innocent peasants starving to death represented the failure of the revolution, while the false accusations against loyal party members represented the corruption of the revolution.

Indeed, many CCP cadres had the mentality of “seizing and ruling tianxia” (天下, all under heaven) as seen in Chinese history, enjoying various privileges and forgetting their initial revolutionary intentions, which Chairman Mao criticised as bureaucratism.

However, more high-level cadres merely went back to the pragmatism of human nature, believing that the common people should be allowed to recuperate, go back to a normal life and build up strength, while the government should do a good job in basic tasks such as the economy, industry, agriculture, education, transportation, and urban and rural construction, without being unrealistic or rushed. They supported the pragmatic policies of Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.

At this point, the targets of the struggle were fully revealed — the bureaucratic system led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, essentially the entire CCP administrative system.

When the Cultural Revolution began, high-level cadres initially thought it only targeted some people in the media, education and literary circles, as mentioned in party meeting notices. They never expected to be the real target, stuck with overwhelming force.

In August, Mao Zedong issued the “Bombard the Headquarters — My First Big-Character Poster”, accusing certain leading comrades from the central to local levels of “implementing a bourgeois dictatorship and suppressing the proletarian Cultural Revolution”.

Subsequently, General Lin Biao, who had recently been promoted by Mao to help control military power, explicitly criticised Liu Shaoqi. Lin was a general with illustrious achievements in the CCP revolution, and during the failure of the Great Leap Forward, he actively defended Mao’s position. Before the Cultural Revolution, he was promoted by Mao to ensure the military’s support for the Cultural Revolution and to maintain basic stability and order within and outside China amid potential chaos.

At this point, the targets of the struggle were fully revealed — the bureaucratic system led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, essentially the entire CCP administrative system.

As for how to criticise and to what extent, even the battle-hardened Communist cadres could not make an assessment based on past experience. It was only when the Red Guards ordered them to kneel and had struck them mercilessly that they realised they were now lambs awaiting slaughter.

Hypnotised nation and a god-like leader

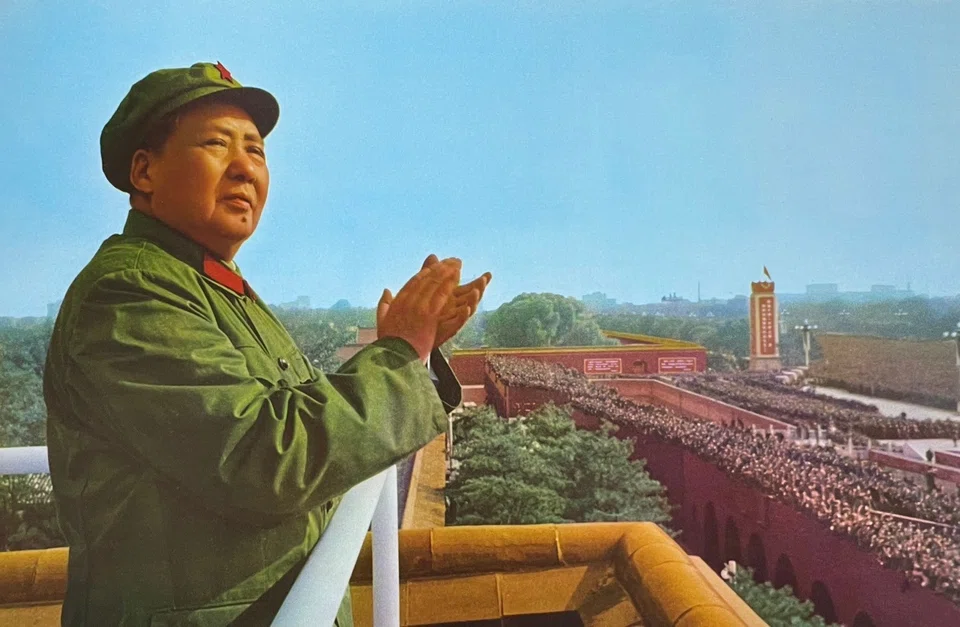

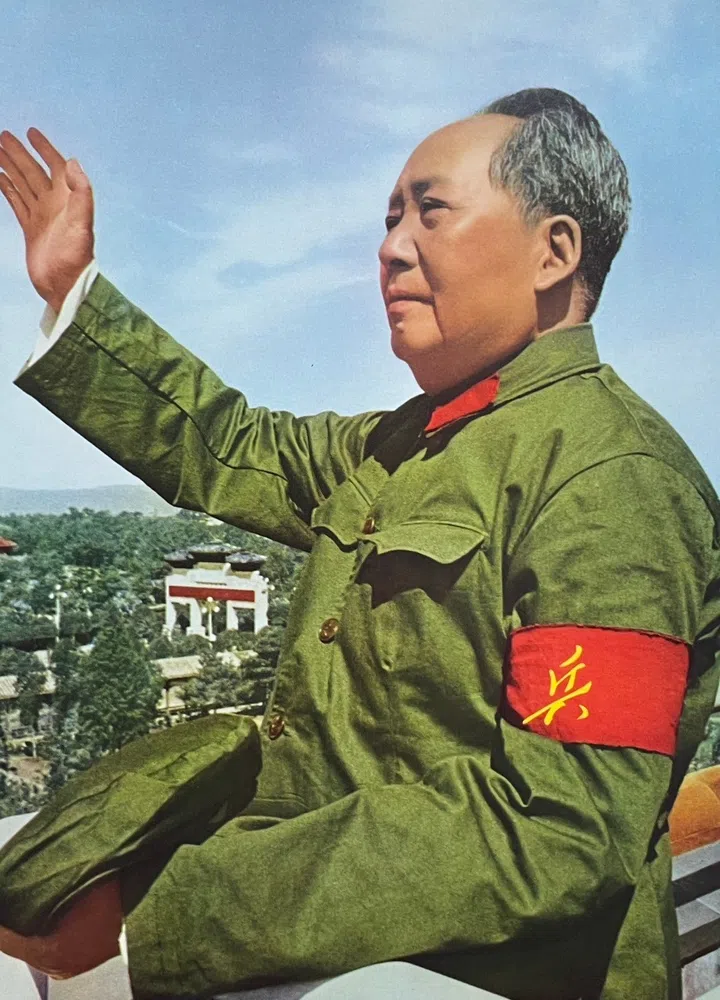

Soon, the world-renowned grand scenes of the Chinese Cultural Revolution appeared, with Chairman Mao meeting a million Red Guards in Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

The young people’s inherent passion and impulsiveness, driven by a sense of justice, led them to be more violent and brutal than adults.

Young students from all over the country gazed at Mao on the city tower, waved the Little Red Book and chanted “Long live Chairman Mao!” with tears of excitement, feeling overwhelmingly inspired. Absolute power cannot exist without the frenzy of the masses; the climax of the revolution was accompanied by the populace being hypnotised by a few simple slogans and a prophet-like, god-like leader. This has happened multiple times in modern human history, but this time it occurred in Confucian-centric, secular China with its ethics of the day.

These young students were between 15 and 25 years old. When the new China was founded, they were either very young or not yet born. In an environment where information was closed, they were like blank sheets of paper carefully painted with the pure red of Mao Zedong Thought, absolutely obedient to the CCP Central Committee.

If the country encountered difficulties, it was due to imperialist oppression and Kuomintang sabotage; if the socialist revolution faced obstacles, it was because bourgeois enemies had emerged within the CCP. The young people’s inherent passion and impulsiveness, driven by a sense of justice, led them to be more violent and brutal than adults.

China’s descent into violence and madness

When the Cultural Revolution began, schools had already stopped classes, because the old knowledge system was essentially a product of the corrupt bourgeoisie. They were to learn and train through real revolutionary action, to destroy the old world and create a new one.

The Red Guards began to fight against school principals and teachers, ransacking homes everywhere targeting “reactionaries” and “bourgeois enemies”, seizing valuable books and antiques, foreign currency, gold and silver treasures, and destroying ancient monuments and cultural relics, causing enormous cultural destruction.

All over the country, cultural items and famous ancient sites that had survived years of war were destroyed, including Confucius’ tomb and plaques in Qufu, Shandong, and the Ming Dynasty Tombs of the Wanli Emperor in Beijing. Students were no longer attending classes; their only activity was squeezing onto free trains to travel around the country, reciting Mao’s quotations, singing revolutionary songs, and learning how to bully and beat people, and destroy things.

In January 1967, Liu Shaoqi’s wife, Wang Guangmei, was tricked into going out, and the Red Guards took her to a mass rally where she was publicly beaten and humiliated.

Energetic young men and women, driven by curiosity and the excitement of the chaos, travelled across much of China. They did not truly understand the meaning of their actions, they were just happy not to have to attend classes, enjoying the revolution and having fun.

In October of that year, Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping were forced to self-criticise. Red Guards in Beijing had already posted big-character posters calling for the removal of Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. In January 1967, Liu Shaoqi’s wife, Wang Guangmei, was tricked into going out, and the Red Guards took her to a mass rally where she was publicly beaten and humiliated. By then, everyone in the CCP’s top ranks was living in fear.

At the same time, under Mao’s directive, rebellious intellectuals and workers in Shanghai rallied millions of people to drag out and criticise the city’s leaders. Their methods were brutal and horrifying, with the masses in a fervour, leading to grand spectacles. With morale at a high, the rebels announced the establishment of the Shanghai Revolutionary Committee, replacing the original city leadership.

Mao Zedong praised the revolutionary action of seizing power in Shanghai, and it was prominently reported and endorsed by central newspapers. Consequently, rebels in various provinces and cities began their own power-seizing actions, establishing local revolutionary committees, with the original leaders being criticised, dismissed, detained and sent down to the countryside.

As the Red Guards attacked party and government institutions with rampant violence, various hostile factions emerged among them, engaging in armed battles complete with knives, clubs and other weapons, including gunfights with seized military weapons in some places. The student revolution started turning into young bodies lying in the streets, and the many well-known intellectuals who were criticised were brutally beaten to death. Many others, unable to endure the physical and mental torture, chose to end their lives. China descended into endless violence and madness.

Harsh reality of rural life

As the situation spiralled out of control, production activities were severely disrupted, threatening the stability of the central government. Mao Zedong called for schools to resume classes and dispatched work teams to schools to limit excessive fighting.

By now, the leaders of party and government institutions across the country had been overthrown and replaced by rebels completely loyal to Mao’s line. Students rampaging through society were detrimental to the new order, so Mao sought to reap the rewards while also reining in the chaos.

During a party meeting in 1968, Liu Shaoqi was convicted as a “criminal traitor, enemy agent and scab in the service of imperialists” and permanently expelled from the party. He and another founding marshal, He Long, were exiled and imprisoned; both died in misery the following year. Meanwhile, Mao prevented the rebels from completely eliminating Deng Xiaoping, instead sending him to a factory in Jiangxi, leaving a way out for him.

At the end of 1968, Mao Zedong also ordered students across the country to go to the countryside to be “re-educated by the poor and lower-middle peasants”. Over ten million educated youths from various provinces boarded trains and buses, bid farewell to their families, and headed in vast numbers to northeast China, Xinjiang, Yunnan and other northern border areas, as well as remote rural areas in various provinces. They formed “production brigades” and engaged in arduous work such as opening up land and reclaiming wasteland with their own hands.

Their idyllic fantasies of rural life were quickly shattered by harsh reality: simple houses, lack of water and electricity, food shortages, no medical supplies, long hours of physical labour, and repetitive political studies. A big question soon arose in their minds: Was this to be their future life?

The stance of strutting around and causing trouble on the streets just two years earlier had evolved into being tied down in remote rural areas. No matter how the newspapers glorified rural life, they had become low-paid agricultural workers whose every move needed approval.

After this fundamental change in their roles, they gradually formed their own opinions and became politically mature. This generation, who were educated purely in Maoist thought and forced to leave their families and endure a materially deprived rural life, began to realise that the world was not necessarily as Mao had described it, and that “bourgeois enemies” were not necessarily all bad people.

In the spring of 1969, the CCP held the famous Ninth National Congress. Apart from severely criticising Liu Shaoqi, Vice Chairman Lin Biao was made Mao’s successor in the party constitution. Major rebel leaders, including Mao’s wife Jiang Qing and others like Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan, and Wang Hongwen, who had pioneered the power seizure in Shanghai, were all included in the leadership team.

At this point, all of China was under Mao’s faction, yet Mao still felt insecure.

The Cultural Revolution faction’s power surged — they all loudly proclaimed “Long live Chairman Mao” and defended Mao’s directives. At this point, all of China was under Mao’s faction, yet Mao still felt insecure. He was unsure whether these rebels were truly loyal or just pretending, using Mao Zedong Thought as a facade to purge those they disliked, seize resources and gain personal benefits.

Cracks in Mao Zedong and Lin Biao’s relationship

At this time, an armed conflict erupted between China and the Soviet Union, shocking the international community. After Sino-Soviet relations soured, the two countries not only engaged in ideological disputes but also vied for international influence within the communist countries and third world or developing countries.

Furthermore, on Zhenbao Island or Damansky Island in the Ussuri River, a border conflict ensued, with both sides engaging in military skirmishes involving tanks and rocket artillery, approaching a state of war. The Soviet Union even threatened to use nuclear weapons, leading to a Sino-Soviet nuclear crisis. In preparation for nuclear war, China dug large underground tunnels in the Beijing area. Lin Biao, responsible for military defence, held wartime command authority and could deploy military forces, significantly increasing his power. All this contributed to Mao Zedong’s unease.

The relationship between Mao and Lin began to show cracks over minor issues. During the civil war, Lin had led the largest contingent of Communist troops, and his former subordinates now held key positions in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), including the highly mobile Air Force. A breakdown in Mao-Lin relations risked large-scale civil war.

Starting in 1971, Mao’s criticisms of Lin Biao became increasingly public, and their relationship grew ever more tense. On 13 September, following a failed coup attempt, Lin Biao, along with his wife, family and several close associates, boarded a plane to flee to the Soviet Union. Due to insufficient fuel, the plane crashed in Mongolia, killing everyone on board.

The so-called loyalty to ideology, leader and country — none of it was real, but mere propaganda, utterly discrediting all the slogans of the Cultural Revolution.

After Lin Biao’s death, China immediately went into a state of high alert, and Lin’s key subordinates were isolated and investigated. In an effort to save his own life, the highest military commander against the Soviet Union ultimately attempted to defect to the enemy. The so-called loyalty to ideology, leader and country — none of it was real, but mere propaganda, utterly discrediting all the slogans of the Cultural Revolution.

The authorities kept the truth of Lin Biao’s defection and death from the people, quietly erasing his name and continuing to hunt down his followers nationwide. It was only about two years later that Lin’s death was officially announced.

Many educated youths who had been sent to the countryside later reflected that the news of Lin Biao’s death was a turning point in the spirit of the Cultural Revolution. Although it was never explicitly stated, they had an internal awakening, deeply questioning the meaning of the Cultural Revolution.

They realised they were mere pawns, deceived and exploited, some even becoming perpetrators, ultimately forced to abandon their studies and waste the prime years of their youth.

A worldwide phenomenon

To understand the reflections of this revolutionary youth, we must connect it to the wave of socialist revolutions around the world. The Cultural Revolution not only swept through China like a mighty storm, but also stirred up a global left-wing movement. The brutal images of the US involvement in Vietnam War televised globally spurred worldwide left-wing armed revolutions. Mao Zedong positioned China as the centre of third-world revolutions, providing concrete support to communist parties in various countries through weapons and aid.

In Asia, the Red Khmer and the Malayan Communist Party were inspired and called to action, while Japan saw the emergence of Maoist armed guerrilla teams. In Paris, left-wing students imitated the Chinese Cultural Revolution’s demonstrations and violence, and Europe witnessed various Maoist armed struggles, including terrorist activities such as bombings and assassinations, echoing a world revolution.

In the Americas and Africa, various communist organisations became more active, with the Cuban Revolution being the most notable, led by Che Guevara, a famous Maoist, who gave up his family to continue the revolution, like a Robin Hood in the forest, providing free medical care to the poor and fighting against right-wing military dictatorships. His ultimate sacrifice became a poetic ending for socialist martyrs, making his image a symbol of revolutionary ideals for generations of youth.

In fact, from the mid-19th century, the tide of anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism that rose in Europe reached its peak with the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1917 and the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and the flame continued to burn fiercely. The left-wing student movement of the 1950s and 1960s was like a storm that swept through, leaving an unforgettable memory for many individuals.

The Asian, African and Latin American socialist youths who came to Beijing with a pilgrim’s heart were no less excited than local Chinese revolutionary students when they saw Chairman Mao in person.

While the Prague Spring broke out in 1968, with anti-communist sentiments surging in Eastern Europe, it is essential to clarify the fundamental difference: the communist regimes in Eastern Europe were products of Soviet military occupation, not self-established through local historical conditions. Anti-Soviet and anti-communist sentiments were the main forms of nationalism in those regions.

In contrast, the left-wing revolutions in China and Asia, Africa and Latin America were solutions to their own social contradictions, carrying sentiments of anti-Western capitalism and post-colonial nationalist democracy, which was the opposite of Eastern European countries.

Furthermore, in the mid-1970s, the communist revolutions in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos succeeded, marking the peak of the socialist revolutionary wave that had lasted for nearly 60 years. However, the Soviet Union, the source of the revolution, was rapidly declining, and the dreams and hopes brought by the Cultural Revolution for the extreme left in China ultimately proved to be a fleeting illusion.

As the cruel truth gradually came to light, it was confirmed to be a nightmare.

Rise of Deng Xiaoping

Lin Biao’s death not only shook the faith of young people in the Cultural Revolution, but also deeply affected Mao Zedong’s mental state. The party’s number one successor, who had always shouted “Long live Chairman Mao”, was actually ready to destroy Mao. Mao suddenly remembered the old cadres who had been persecuted by Lin Biao and felt that the Cultural Revolution had gone too far.

In early 1972, he took the initiative to propose letting Deng Xiaoping return to work, and Deng, after learning about it, wrote a long letter to Mao, acknowledging his past mistakes, hoping to work again and promising never to rebel. Therefore, Mao decided to use Deng again, and under the arrangement of Premier Zhou Enlai, Deng resumed his duties as vice-premier and assisted Zhou in handling foreign affairs.

The relationship between Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping in the CCP’s history should be briefly explained. Mao and Zhou were of the same generation, and Zhou was even Mao’s leader at one time. However, Mao’s outstanding strategic thinking and courage enabled him to become the highest leader, while Zhou’s skill in organisation, coordination and propaganda made him the second-in-command.

Mao Zedong once described Deng Xiaoping as “a needle hidden in cotton”, meaning that while appearing gentle on the surface, he was actually sharp and able to accurately judge the overall situation, like a needle piercing the core of the issue.

After Mao established his absolute authority in the party, Zhou cautiously assisted Mao and never dared to overstep his bounds, like a wise and loyal prime minister next to the emperor in ancient China.

During the Cultural Revolution, Zhou faced the rebels with trepidation, faithfully executing Mao’s will to send many old cadres to prison but yet secretly protecting them. Mao purged many veteran revolutionaries, but kept Zhou by his side because he knew Zhou was loyal and reliable, and a useful balance in the power struggle.

As for Deng Xiaoping, he was younger than Mao and Zhou, but joined the party early and worked in the central government, mainly doing administrative work, such as recording and secretarial tasks, as well as political propaganda. He was once criticised for supporting Mao’s pragmatic policies and opposing the party’s radical approach, which led to his dismissal. Mao therefore had a certain historical sentiment towards him.

In the early years of communist China, Deng Xiaoping was not as prominent as the main founders, and it was not until his resurgence that people began to study him more deeply.

He and Zhou Enlai had known each other in Paris, and their talents lay not in military command but in propaganda, organisation and administration. They took a pragmatic approach to solving problems, unlike Mao, who had spent his life in rural China, leading the revolution, and often viewing the world in simplistic terms. Zhou and Deng, on the other hand, had lived in Western society, seen the actual operation of Western industry, and demonstrated a deep understanding of concrete details.

Mao Zedong once described Deng Xiaoping as “a needle hidden in cotton”, meaning that while appearing gentle on the surface, he was actually sharp and able to accurately judge the overall situation, like a needle piercing the core of the issue.

From 1973, Deng gradually re-entered the leadership core, taking on more responsibilities as Zhou Enlai’s health declined. Despite the damage caused by the Cultural Revolution, Deng developed science and technology, gradually restoring normal production activities. These pragmatic policies immediately drew opposition from the Cultural Revolution faction, with both sides vying for Mao’s support. Eventually, Mao supported Deng as the second-in-command of the party, government and military, to balance the extreme tendencies of the Cultural Revolution faction.

In 1975, Zhou Enlai proposed the task of “Four Modernisations” at a party meeting, namely modernising industry, agriculture, national defence, and science and technology. This indicated that China would shift its focus from class struggle back to economic construction, essentially reversing many of the Cultural Revolution’s policies.

Mao also felt that Deng was going too far and instructed party newspapers to criticise current policies. The significant change in political direction immediately triggered a power struggle, which quickly escalated into a showdown.

In January 1976, Zhou Enlai passed away, and the people held mourning activities across the country. The Cultural Revolution faction seized the opportunity to launch political attacks on Deng Xiaoping and other pragmatic leaders, openly criticising them.

Meanwhile, Mao instructed the military to protect Deng’s residence, effectively placing him under house arrest, and appointed Hua Guofeng as acting premier. Mao chose a leader with a relatively shallow revolutionary background and no clear factional affiliation to balance the power between the Cultural Revolution faction, the government and the military.

However, public discontent had already reached a boiling point, and the situation quickly escalated beyond the expectations of Mao and the Cultural Revolution faction.

Public anger towards the Cultural Revolution

On 4 and 5 April, crowds gathered in Tiananmen Square to mourn Zhou Enlai during the Qingming Festival. In the eyes of the people, Zhou was like a loyal and righteous official from ancient times, dedicated to his duties, dedicated to the country and uncorrupted; his unjust treatment by the Cultural Revolution faction was unbearable.

In his later years, Zhou Enlai had been constantly harassed and intimidated by Jiang Qing and other Cultural Revolution leaders, leading to widespread resentment among the people. As they offered flowers for their sympathy for Zhou, the crowd expressed their anger towards the Cultural Revolution faction and their backward policies. The protesters wrote many moving poems and openly declared that “the era of Qin Shi Huang has passed”.

Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor to unify China around 200 BC, ruled with brutality, forcing labourers to build the Great Wall, burning books and burying scholars alive. China’s Confucian tradition emphasises benevolent rule, so Qin Shi Huang is regarded as a tyrant, condemned and rejected.

The crowd’s chant, “The era of Qin Shi Huang has passed”, directly targeted Mao Zedong, who was still alive at the time. The tragedy of the Cultural Revolution had already broken Mao’s divine status, and the people were fed up with the endless political struggles and dared to stand up against the authorities.

The Cultural Revolution faction, consisting of a few propaganda officials who relied on Mao’s support to rise to power, had a weak social foundation.

In the face of the sudden and massive crowd protests, the authorities dispatched tens of thousands of militia to disperse the demonstrators and arrested several people. The party’s newspaper quickly labelled it a “counter-revolutionary incident”, and Deng Xiaoping was stripped of all his party, government and military positions by Mao, leaving him only a party member. He was accused of being the mastermind behind the incident.

However, support for Deng Xiaoping came not only from the broad masses but also from high-ranking officials in the party, government and military, who held real political power. The Cultural Revolution faction, consisting of a few propaganda officials who relied on Mao’s support to rise to power, had a weak social foundation.

On 9 September, Mao Zedong finally passed away, and China plunged into a state of mourning. The Cultural Revolution faction accelerated their plan to seize power, but they were vulnerable without Mao’s support.

On 6 October, Hua Guofeng, together with Beijing’s military leaders, used a meeting as a pretext to arrest the “Gang of Four”, consisting of Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, and three other officials who rose to power during the Cultural Revolution: Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan and Wang Hongwen. They relied on Mao’s support to control the party and propaganda machine, but by the end of the Cultural Revolution, they were widely detested by both old cadres and ordinary citizens, leading to their arrest without any significant resistance from their followers across the country.

Growing support for Deng

Hua Guofeng seized power through a political coup, nipping in the bud a potential civil war without firing a shot; people within and outside of China were stunned and impressed. However, on closer examination, such a decisive move was perhaps not so surprising.

With Deng Xiaoping already ousted, Hua Guofeng naturally became the first target of the Gang of Four’s power grab. Given their ruthless tactics and lack of popular support, it was better to strike first and arrest the Gang of Four, to gain power and popular support. Indeed, Hua Guofeng quickly gained support and became the top leader of the party, government and military after Mao’s death and the downfall of the Gang of Four.

However, a second round of power struggle soon emerged, with Hua Guofeng’s revolutionary credentials deemed insufficient. He faced pressure from veteran officials demanding Deng Xiaoping’s reinstatement. Hua’s power was mainly derived from Mao’s patronage, and he insisted on following Mao’s instructions to the letter, opposing Deng’s return to power.

Nevertheless, the party’s demand for Deng’s reinstatement grew increasingly strong, forcing Hua to relent. A year later, Deng Xiaoping finally resumed all his positions, becoming the second-in-command of the party, government and military.

Now, with Mao’s death and the Gang of Four’s downfall, Hua Guofeng’s influence waned. Amid the people’s longing for normal national development, Deng Xiaoping’s political strength was formidable, enjoying high expectations from within and outside the party. This time, no one could stop him. He immediately took concrete measures to make up for the damage caused by the Cultural Revolution.

Universities reopened, and thousands of young people who had been sent to the countryside applied to return to the cities and enter university — they had already applied to go back to the cities for all sorts of reasons over the past few years.

They were not old, but they had spent their youth in rural areas, doing manual labour; even if they were intelligent, they had no opportunity for higher knowledge. They had no access to libraries and books, or to interact with foreign lecturers and students, much less travel abroad and see the world for themselves.

The phrase “going to the countryside to make it big” became synonymous with “missing out on higher education opportunities”. They refused to be deceived again, asking to return to the cities through petitions, hunger strikes and even lying on railroad tracks, creating moving scenes as these weary youths held signs saying “Give me back my youth”.

By the time they entered university at the age of 27-30, they cherished the opportunity to learn after ten years of hardship. Some of this generation of educated youth remained in rural areas, got married and had children; others went on to achieve academic success in Europe, the US and Japan, gaining a broader perspective of the world. Many also became the first generation of private entrepreneurs.

Regardless of the path they took, the educated youth of the Cultural Revolution era left a profound mark on Chinese society, politics, economy, culture and literature.

As for the large number of veteran officials who were directly persecuted and imprisoned by the Gang of Four, they were cleared and released, while the “rightists” who were labelled as such during the Anti-Rightist Campaign also had their labels removed and their social rights restored.

Deng Xiaoping’s bold reforms made up for the social damage caused by the Cultural Revolution and the Anti-Rightist Campaign, promoting social reconciliation and normal development.

However, after 30 years of education and indoctrination, Mao Zedong Thought remained deeply rooted, determining the basic logic of political and economic development, and deeply influencing the thinking patterns of intellectuals.

A new philosophical perspective was needed to free the Chinese people from their collective and individual mental shackles, as well as a new theoretical framework to dismantle the ideological fortress of the extreme left.

Policies based on modern empiricism

After careful planning and discussion, Deng Xiaoping’s key political ally published an article in the newspaper titled “Practice is the Sole Criterion for Testing Truth”. This article was like a bombshell, seen as the theoretical representation of Deng Xiaoping’s thought, and the basic logic for China’s progress after the Cultural Revolution. On the surface, the article was criticising Hua Guofeng’s dogmatism, with a tone of realpolitik, but in reality, it went far beyond that, targeting communism itself.

Karl Marx argued that the history of humanity is essentially one of class struggle, and that the means of production determine production relations, which in turn determine the superstructure. The industrial revolution deepened class contradictions, so the proletariat should use violence to overthrow the capitalist class, establish a dictatorship, and eliminate private ownership, the source of greed and exploitation. This way, everyone can develop their talents and receive what they need. After a period of building socialism, classes would naturally disappear, and a communist paradise would emerge.

If Deng’s pragmatic thinking becomes the mainstream value in China, as well as the criteria for political and economic policies, to a certain extent, communism would cease to exist.

Although Marxism is theoretically founded on dialectical materialism, the Communist Party’s approach to gaining power is highly ideological. Communist Party members do not treat communism as a theory but as the only truth, an unquestionable faith. They view the temptations of the capitalist class as spiritual demons, purging their inner demons through self-criticism; they also criticise one another in groups, for collective redemption and spiritual sublimation.

The Communist Party’s collective has a strong religious flavour, with Marx’s words the instructions of a deceased prophet, repeatedly quoted by his successors, often leading to mass emotional arousal and even tears.

Such spiritual mobilisation is a lot like primitive monotheism, and once it takes hold, it will create a theocratic society, thoroughly destroying other thoughts and beliefs. Therefore, communism, although claimed to be scientific, is actually closer to theology, providing a priori moral principles and a vision of ultimate human happiness, while being an unquestionable absoluteness and truth.

The theoretical basis for supporting Deng Xiaoping’s policies — “Practice is the Sole Criterion for Testing Truth” — comes from modern empiricism. It believes that only practical operation can form stable and trustworthy behavioural patterns and moral norms.

Empiricism objects to political dogmatism, believing that using political power to forcibly promote unproven moral principles will lead to major tragedy. Empiricism also objects to political utopianism, making it the natural enemy of communism.

In simple terms, if communism was God, Deng Xiaoping was saying, “I want to see God’s true face before I believe.”

He often quoted a saying from his hometown in Sichuan: “No matter if the cat is black or white, as long as it can catch mice, it’s a good cat.” This means that if communism cannot bring happiness to the people, then use other isms!

If Deng’s pragmatic thinking becomes the mainstream value in China, as well as the criteria for political and economic policies, to a certain extent, communism would cease to exist. The CCP would become a party without communism, and it would need to find other spiritual pillars.

In any case, China has already determined its new development thinking, but in line with its pragmatic initiative, it needs to continuously consolidate its achievements through work and transform them into sustained spiritual momentum.

Helmsman Deng Xiaoping led the giant ship that is China in executing a major turn, and given the ship’s massive size, even on a calm sea, it would stir up thousands of waves. When the winds and clouds change, there would also be risks of the ship capsizing.

China must bravely navigate the risks of this major turn, which will also determine the historical landscape of China and the entire human race for the next 20 years.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)