Will US chip controls work on China?

Analyst John Lee assesses the impact of US chip controls on China, pointing out the little likelihood of complete decoupling, especially in areas out of high-end chips. Despite the restrictions, China has options of its own but the tides could change at any minute in this "competition to win the 21st century".

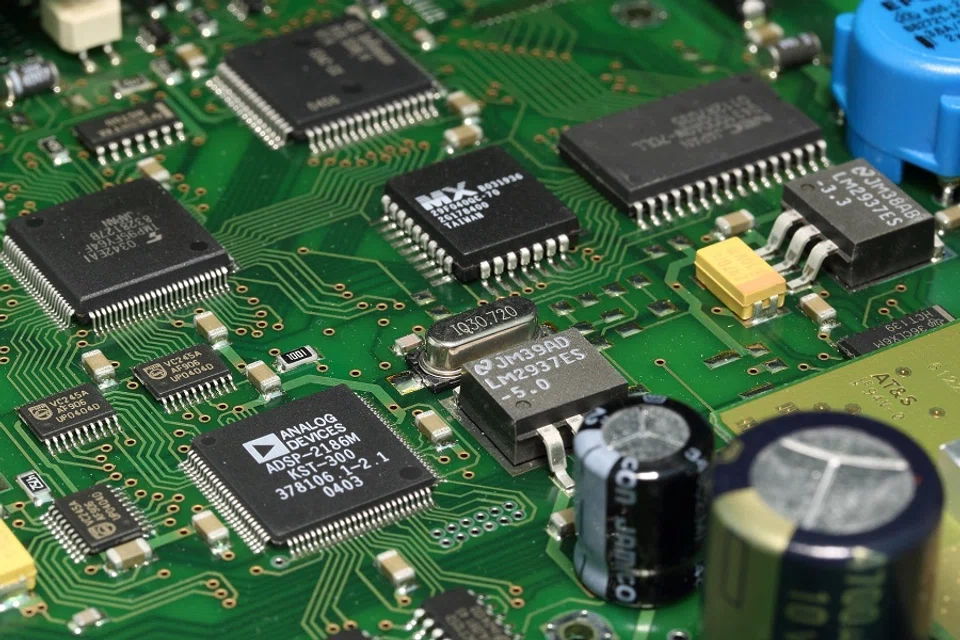

The sweeping US export controls imposed in October on China's semiconductor sector are a major escalation from US-China trade tensions to date: they are the first shot in a campaign of true technological containment.

The US government has decided that it must constrain China's access to the most foundational technology for computing power - not just through restrictions on individual firms, but by targeting the whole Chinese economy. Washington has also decided that it cannot wait for cooperation from third countries but must act unilaterally, in the expectation that its allies and partners will follow.

More measures targeting Chinese access to more technologies will likely follow, as the US commits fully to what President Biden has called "a competition to win the 21st Century".

As put by Biden's national security adviser Jake Sullivan, the goal is no longer to keep China just a couple of technological generations behind the US, but to make this gap as wide as possible. This is not just about Chinese military capacity, which is the nominal justification for the US new controls. At stake are the global impacts of the industrial policy model that drives China's technological advance.

The dominance of US firms and US-origin technology in parts of this value chain, notably manufacturing equipment and software tools, gives Washington the leverage to cut China off from foreign vendors...

As the US Trade Representative Katherine Tai recently said, in Washington these impacts are viewed as a threat to the economic survival of free societies, requiring a paradigm change in the attitude to global trade and its national security implications.

Closing in

For China, the chokepoints in the global semiconductor value chain leave it with few good short-term options. The dominance of US firms and US-origin technology in parts of this value chain, notably manufacturing equipment and software tools, gives Washington the leverage to cut China off from foreign vendors in this highly specialised industry. The world's leading foundries, most critically Taiwan's TSMC, will not risk violating US law to make high-end chips for Chinese customers.

China is accelerating efforts to build "de-Americanised" fabs (fabrication plants), but these would still depend on foreign suppliers. Even if Japanese or European firms are willing to sell equipment to Chinese customers, they would need to independently develop many items to shield themselves from extraterritorial US jurisdiction. And the "US persons" provisions in the October export controls now make it highly risky for US semiconductor firms to continue selling to Chinese customers through shell companies or by offshoring their activities.

... it may be most of a decade before China fills the gaps for a capacity to manufacture today's most powerful computer processors at scale.

In the meantime, China's import substitution efforts across the vast range of items needed for semiconductor fabrication remain a long and hard road. In the critical chokepoint of photolithography - where Netherlands firm ASML is a global monopolist at the technology's cutting edge - it may be most of a decade before China fills the gaps for a capacity to manufacture today's most powerful computer processors at scale.

Not without options

This does not mean that China's role in the global electronics sector, and the emerging technology stacks built upon it, is now crippled. China's central role in manufacturing, including for new technologies such as electric vehicles, will not be easily disrupted.

The series of decoupling measures from Washington over the past half decade has not stopped foreign industry leaders from doubling down on China or developing separate supply chains for China to avoid US controls. In the semiconductor value chain itself, China already has a significant presence that creates inertia against attempts to "reshore" or "friendshore" activity in certain segments away from the Chinese mainland.

In particular, China's growing share of "trailing-edge" fabrication will be difficult to replicate elsewhere in the short term. Such older generation fabs cannot manufacture cutting-edge processors or memory chips, but they do make the types of chips that suffered a supply crunch over 2020-2021, focusing policymakers' attention on the globalised semiconductor supply chain and its risks.

As for high-end chips, Chinese actors may be able to obtain these through the black market.

However, the rash of policies designed to incentivise fab construction on home territory has not changed the huge expense and long lead times involved, or the limited capacity of equipment manufacturers to service such new facilities.

Accordingly, while the scope of the new controls gives US authorities the option to target a wider range of economic activity in China requiring high-end chips, this is unlikely to be exercised in the short term. US officials have already conveyed that there is no intent to use the new export controls to target China's role in making chips for car airbags, or for a myriad of other mundane but essential functions required by a range of end user industries.

Decoupling harder than one thinks

As for high-end chips, Chinese actors may be able to obtain these through the black market. Russia has for years obtained enough export-controlled chips from Western manufacturers to equip a large military force, including continuing production ten months into the war in Ukraine. And the incentives to risk the wrath of US authorities are much greater when selling to China.

However, it is hard to see such channels providing the volume and reliability needed to support the Chinese state's huge ambitions for nationwide big data processing networks and other "new infrastructure" that requires copious computer processing power.

Perhaps the most critical factor is the willingness of third-party governments to align their own regulations with US measures targeting China.

Perhaps the most critical factor is the willingness of third-party governments to align their own regulations with US measures targeting China. The US is currently pressuring the Netherlands and Japan, as key semiconductor manufacturing jurisdictions, to do so regarding the October export controls. But unless Washington is prepared to really "bring the hammer down" on friendly countries, it will likely achieve at best "patchwork decoupling" from China, far from an international zone free of Chinese technology.

China's ties with its own neighbourhood especially have been growing denser, despite US pressure, through the links of digital technology and its steady extension throughout society. This Gordian Knot of interdependence will only be cut through drastic measures from Washington, which effectively force third parties to choose between maintaining economic relations with the US or China, with all the costs and risks that entails. Whether these new export controls targeting semiconductors are sufficiently drastic remains to be seen.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)