[Photo story] The historical aftermath of Japan's colonisation of Taiwan

Japan's colonisation of Taiwan after the First Sino-Japanese War is a chapter of history that the Chinese would rather forget, along with the pain and suffering that the Japanese inflicted on the people of China and Taiwan. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao gives us an idea of that period.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

From 1895 to 1945, Japan exerted 50 years of colonial rule over Taiwan. After World War II, colonialism was thoroughly rejected, and colonies in the East and West either became independent or returned to their original motherland. Most former colonies settled their status 50 years ago, but while Taiwan was returned to China in 1945, both sides of the Taiwan Strait remain divided today, and there is a psychological shadow of Japan's colonisation of Taiwan.

In 1895, China was defeated by Japan in the First Sino-Japanese War, and was forced in the Treaty of Shimonoseki to cede Taiwan. However, the Taiwanese did not accept this decision and took up arms to resist the Japanese as they arrived to take over. At the same time, it declared the Republic of Formosa - dubbed the "Yongqing" (永清, lit. "Forever Qing") era - and sought the support of the Western powers, declaring that it would return to China following independence.

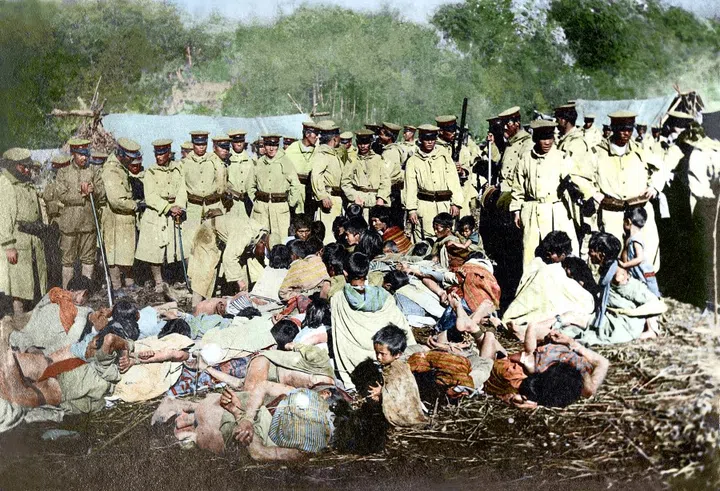

In the face of Taiwanese resistance, Japan shifted the bulk of its sea and land troops in the First Sino-Japanese War to attack Taiwan. With intense resistance from the Taiwanese people, the Japanese army destroyed rural areas with mass killings and burnings, suppressing the resistance only after about five months of fighting. Nevertheless, in the seven years that followed, the Japanese army carried out raids on Taiwanese guerillas in the mountains.

...in 1930 the indigenous people rose up in the Musha incident, and the colonial government activated its troops, aircraft, artillery and even released poison gas, to heavy criticism from the international community.

Mining Taiwan's riches

From 1914, the Japanese colonial government started to deploy troops to attack the indigenous villages that had lived for centuries in the central mountains and eastern Taiwan, for complete control of the mountain areas and to open up the rich resources in the forests.

In the first 20 years of Japanese rule, the Taiwanese - Han and indigenous people alike - never stopped fighting and resisting, and the colonial authorities were always activating the troops to deal with this recurring problem. Nevertheless, in 1930 the indigenous people rose up in the Musha incident, and the colonial government activated its troops, aircraft, artillery and even released poison gas, to heavy criticism from the international community.

Alongside its armed suppression of the Taiwanese resistance, Japan began to carry out the original purpose of the colonial empire's military expansion, which was to exploit the economic interests of the colonies, acquire their raw material resources, exploit their cheap labour force, and use them as a market for the colonial empire's industrial products.

All of Japan's politics, economics, society, education, and even infrastructure in Taiwan were driven by this aim. They quickly conducted a census and studies of land resources in the whole of Taiwan, and then built the North-South Railway.

Taiwan is situated in the Asian tropics, suitable for planting rice, sugar cane and various economic crops not just for Japan's consumption but also to sell all over the world for a significant profit. They built large-scale hydro projects in southern Taiwan, researched improving rice breeds and improved rice quality and production, and thought of Taiwan as the rice silo of the Japanese empire.

In 50 years of Japanese colonial rule, the colonial authorities only nurtured about 200 Taiwanese university students and one Taiwanese university professor.

Restricting access to university education

Because the colonial authorities considered Taiwanese cheap colonial labour, they had to make sure the workers were of a certain standard without having better technical skills than the colonialists. This was to always keep the colonialists ahead in terms of advanced technology and funds.

The Japanese colonial authorities strictly controlled Taiwan's education system, setting up various secondary school-level vocational schools; however, it was not until 1928 that the first university was established, with strict entry restrictions on Taiwanese. In 50 years of Japanese colonial rule, the colonial authorities only nurtured about 200 Taiwanese university students and one Taiwanese university professor. The colonial authorities strictly controlled Taiwanese in receiving higher skills and education.

As for trade and financial governance policies, the colonial authorities were in total control of Taiwan's imports and exports. Taiwanese could not import or export equipment and goods on their own, but had to do it through Japanese trade companies designated by the colonial authorities. Nor could Taiwanese have their own banks - all funding and loans had to be done through Japanese banks. Foreign banks were not allowed to set up branches, or invest or operate in Taiwan, as Taiwan's capital market was completely monopolised by the colonial authorities.

...the Taiwanese were not affluent. In particular, most people in the rural areas were farmers, exploited and living in abject poverty.

Tightly controlled economy but stable

So, as a Japanese colony, Taiwan did not have the thriving economy and diversity of other Western-colonised Southeast Asian cities like Hong Kong, Singapore, Penang, Saigon and Manila. In Taipei, unlike other colonised cities, there were no lively scenes; no bars featuring Caucasian singers; no buzzing nightlife; no literary descriptions of a golden age. It was cold and dead, with a closed economy.

During the time of the Republic, the general impression among the Chinese was that ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia were affluent, but not the Taiwanese. And this was true - the Taiwanese were not affluent. In particular, most people in the rural areas were farmers, exploited and living in abject poverty.

Yet, compared to mainland China, mired in civil war and resisting imperialism, Taiwan under the Japanese was relatively stable. The city centres were modern, while the colonial authorities nurtured Japanese-educated elites and trained them to see the world through Japanese eyes.

After Japan initiated the invasion of China, the colonial authorities embarked on a policy of assimilation...

Policy of assimilation

After Japan initiated the invasion of China, the colonial authorities embarked on a policy of assimilation, banning Chinese language newspapers, suppressing Taiwanese traditional religions and forcing Taiwanese to worship Japanese gods, and encouraging Taiwanese to change to Japanese names. This was the "Imperialisation Policy".

After World War II, Japan also pressed about 200,000 Taiwanese into service in Nanyang (Southeast Asia) as army labourers and translators/interpreters. After WWII, some Taiwanese soldiers in the Japanese army were sentenced to death or long-term imprisonment in the war crime trials in South East Asia.

Taiwan after its return to China

On 25 October 1945, the last Japanese governor-general of Taiwan Rikichi Ando signed the instrument of surrender at Zhongshan Hall in Taipei, after which the Chinese army came in and Taiwan was officially returned to China.

However, the civil war between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party quickly followed in China, and the chaos and shortage of supplies due to the war spread to Taiwan. This situation was not unique to China, because after WWII, the world was ablaze with anti-communism; from Europe to East Asia and Southeast Asia, there were armed conflicts, social unrest and economic difficulties.

On 28 February 1947, there was a mass uprising throughout Taiwan, which the KMT government sent troops to suppress. The incident subsided in about two weeks. But given the casualties and the fact that the situation in Taiwan after returning to China was far from the prosperity the intellectuals had initially hoped for, the resulting wounds were deep.

Wounds between Chinese and Taiwanese

Furthermore, some Taiwanese, after being separated from China for 50 years, were using the language the Japanese used to insult the Chinese to criticise China, deeply wounding the feelings of the Chinese. The latter saw these Taiwanese as traitors and slaves of the old Japanese colonial government, leading to complete opposition and hatred, because of the heavy price the Chinese paid for resisting the Japanese invasion. This is the historical legacy of the Japanese colonisation of Taiwan.

Even today, the wound still hurts. The older generation of the KMT government that was deported to Taiwan are gradually no longer around, while the current ruling party rejects the "one China" policy and is pushing "de-sinicisation" in education and culture as it affirms the history of Japanese colonisation, and also denies Chinese sovereignty of Taiwan.

In the hearts of the Chinese people, there is no doubt that this is a reappearance of the spectre of imperialism that once stained Chinese territory and divided China. The scale and force of the Chinese government's response can be imagined.

The US and Japan support such opposition against mainland China, out of completely different intentions from the earlier time of supporting Chiang Kai-shek. In the hearts of the Chinese people, there is no doubt that this is a reappearance of the spectre of imperialism that once stained Chinese territory and divided China. The scale and force of the Chinese government's response can be imagined.

Related: Taiwan history textbooks makeover: Eliminating country, people, history and culture? | [Video and text] A mountain can have many tigers and every tiger has its own problems | History, collective memory and the beauty of Taiwan's old train stations | [Photo story] The Soong sisters and their place in Chinese modern history | Why Taiwanese are pro-Japan but anti-China | [Photo story] The Cairo Conference and Taiwan's liberation

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)