[Photo story] Fifty years of China-US relations (Part 1)

In the first of a two-part feature, historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao takes a look at the ups and downs between the world's two major powers over the past 50 years, and how China's economy and survival have been tied to the US in various ways.

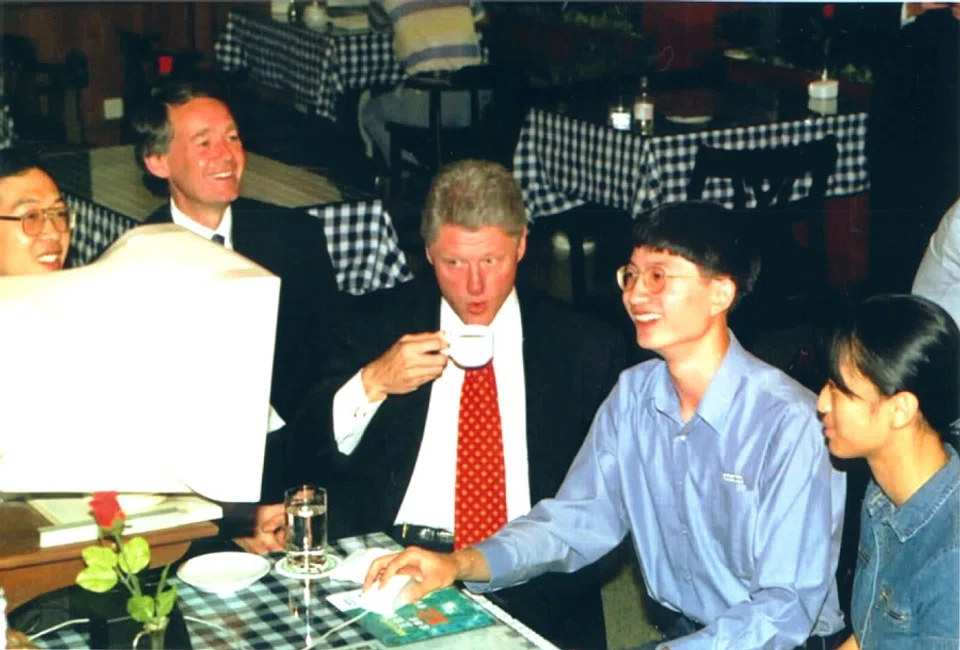

When US President Bill Clinton went to China in 1998, he visited an internet cafe in Shanghai, where he witnessed how the new generation of Chinese youth was using emerging internet technologies to gain new knowledge, establish domestic and international connections, and perhaps even taste the pleasures of online games.

Shanghai was the most advanced city in China at the time, and yet there were only around 30 internet cafes. It was still worth a trip by the US president to see how China was slowly entering the modern world of internet technology.

... the first wave of Chinese tech entrepreneurs made money by selling imported American computers, and were even derogatorily referred to as "profiteers" (倒爷).

In the US's eyes

Back then, the globally recognised Chinese tech giants of today such as Huawei, WeChat, Tencent, Alibaba and TikTok had not yet emerged, while US companies such as IBM, Microsoft and Apple had already penetrated offices globally, and Silicon Valley was attracting many ambitious young tech entrepreneurs who detested the confines of the old ways and were unafraid of failure, and who worked hard to create tech industries in manufacturing, communications and logistics.

This wave of innovation attracted many investors, creating enormous wealth and setting a new trend. What Silicon Valley entrepreneurs wore on the covers of financial magazines often became the fashion, making them the new-generation American heroes that young people sought to emulate.

In contrast, nearly all personal computers in China were imported from the US at the time, and the first wave of Chinese tech entrepreneurs made money by selling imported American computers, and were even derogatorily referred to as "profiteers" (倒爷). The best they could do was to be commissioned by American companies to write computer programmes, getting wages for their intellectual efforts. Mobile phones were also not yet widely used, and most people got in touch by telephone or by leaving messages on pagers. Many Chinese at the time still believed that the best way to improve their economic status was to seek opportunities abroad.

Given the huge gap between China and the US in terms of the tech sector and individual income, President Clinton's visit to the internet cafe in Shanghai was clearly driven by two very American ideas. First, that China was a closed and backward country, and by opening its doors and deeply engaging with it, the US could help China progress, maybe even convert the Chinese to Christianity and stop idol worship. Of course, the US could also open up the Chinese market For over a century, Westerners visiting China held such notions to some degree.

... the US always led the world in innovation. So, it inevitably looked at China's emerging new technologies with curiosity and praise from a position of superiority...

Second, the unique American mindset where the US is the world's technological powerhouse. Whether absorbing talented individuals from abroad or cultivating its own, the US always led the world in innovation. So, it inevitably looked at China's emerging new technologies with curiosity and praise from a position of superiority, like Americans visiting an African tribal family for the first time and applauding their newly installed computer - an American computer at that.

However, nearly 30 years later, while the people are somewhat stuck in stereotypical impressions of the past, China's overall economy has quickly surpassed that of the UK, Germany, Japan and others, to become the world's second largest economy, and expected to surpass the US to become the world's largest economy.

What surprises Americans even more is that the mainstay of China's economy is no longer the traditional image of Chinatown's barbecue shops, illegal labourers toiling day and night to send home their hard-earned money, or gaining ill-gotten wealth by pushing up property prices in major cities in recent years and incurring public wrath. Instead, it is challenging the US in its strongest area of technological innovation. Even its soft power, such as TikTok, is steadily advancing.

American politicians quickly offer the simple answers that the average American voter needs, such as allegations of Chinese theft of US technology or low-wage Chinese workers taking away American jobs. These criticisms imply that Chinese people could never catch up with let alone surpass the technological level of the US through their own original capabilities.

But is this really the case? What has happened in China over the past 20 years? How has China's major transformation affected China-US relations? What options are there for future China-US relations and the global landscape?

Survival needs taking precedence over moral values

For individuals and nations alike, external relations are always tied to survival and moral values, with survival taking precedence over morality. Throughout history, there are many examples of how, for the sake of survival, even the most religious countries have joined those with very different beliefs to fight against those with more similar beliefs.

When US President Richard Nixon took the initiative to visit Beijing to sign the Shanghai Communique in 1972, China was at the peak of the ultra-left Cultural Revolution, with values that seemed the polar opposite from those of the US. Nevertheless, China and the US shared a common interest of survival, as they both faced the danger of a full-scale war with the Soviet Union. China and the US established offices in each other's capitals and subsequently formalised diplomatic relations in 1979.

A month after Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping's visit to the US, China launched a lightning-fast war against Vietnam, achieving the political goal of stopping Vietnam's expansion into the Indochinese peninsula. Interestingly, this was the reason for the US's intervention in the Vietnam War, but now it was executed by communist China.

... the West did not need to open China's door; Deng actively opened it.

However, during Deng's time, China-US relations went beyond geopolitical cooperation. As China sought to move away from Mao Zedong's ideology and embark on economic development, it needed Western and Japanese capital, technology and management methods. This time, the West did not need to open China's door; Deng actively opened it. This young architect of Chinese reform had spent many years in France and believed that while things coming in from the outside world could be good or bad, ultimately there was nothing to fear.

Most importantly, he saw that the outside world could help the Chinese people break free from their closed and conservative mindset, as the modernisation of thought was the foundation for building modernisation. Deng knew that openness would bring about a qualitative change in China, but the extent of the change, which had even led to internal party divisions and social unrest, was unexpected.

Tough stance against the UK

The policy of reform and opening up first began in rural areas, by simply releasing the land to farmers to cultivate. As long as they paid a fixed amount to the government, the rest belonged to them. As a result, farmers worked hard, and the free market for agricultural products immediately came alive. In just five years, many rural areas moved out of extreme poverty, and the traditionally prosperous regions such as Jiangnan quickly regained their affluence.

The government also established four economic zones in Guangdong and Fujian, building infrastructure, providing incentives, and attracting foreign investment to set up processing plants whereby the goods produced could then be exported or supplied to the Chinese market.

In 1984, the fifth year of China's reform and opening up, society showed signs of vigorous development, and Deng's political reputation reached its peak. This was also the year the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed, confirming the return of Hong Kong and Kowloon to China in 1997. At that time, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, known for her tough stance and recent victory in the Falklands War, insisted that based on the 1842 treaty, Hong Kong was permanently ceded to the UK. However, this time she was not facing Argentina, but the new China.

From 1950, China fought against the world's most powerful US military in the Korean Peninsula for three years; in 1962, it defeated the Indian army but refrained from advancing further into Indian territory; in 1980, it sent troops to punish Vietnam, which it was at war with for decades - China was not afraid of military confrontation with the UK.

Today, not a word of this unsavoury history of the British empire as a legal armed drug trafficking group is mentioned in British textbooks, but the Chinese vividly remember it...

Deng demanded the full return of Hong Kong and Kowloon and grew impatient with the UK's diplomatic delay and ambiguity. The Chinese government set a deadline to reach an agreement, otherwise they would unilaterally announce a plan to take back Hong Kong. At this point, the UK had no choice but to give in entirely, ceding in the hope of preserving the interests of British merchants in Hong Kong. Most British felt that Hong Kong's thriving economy and its lifestyle of freedom should be maintained. While the Chinese did not oppose this, they still held a firmer stance.

In 1839, the Chinese government confiscated the opium that British merchants were shipping to China, and the British Parliament started a war against China - the Opium Wars - in the name of "protecting free trade".

In other words, because China confiscated and destroyed the drugs sold by British merchants, Britain sent a fleet to teach China a lesson, forcing them to cede Hong Kong, pay indemnity, and continue the consumption of the drugs sold by the British. Today, not a word of this unsavoury history of the British empire as a legal armed drug trafficking group is mentioned in British textbooks, but the Chinese vividly remember it, and so they are especially outraged at any self-glorifying statements by the British on the Hong Kong issue.

Deng Xiaoping proposed the "one country, two systems" policy for Hong Kong, aiming to strike a balance between national sovereignty and historical realities. But at the peak of Deng's significant achievements in domestic and foreign policies, a significant crisis was brewing within China.

Belief in Western representative politics

In 1984, US President Ronald Reagan's visit to China and his speech at Fudan University in Shanghai took China by storm. The humorous and jovial US president with the charming smile spoke about the values of freedom, equality and justice in the US, recalling the heartwarming stories of cooperation between the US and China during the Second World War. He promoted American values and appealed to the historical sentiments of the Chinese, while carefully avoiding offending the dignity of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Reagan seemed to be liked by everyone wherever he went, and the Chinese were no exception. For the Chinese, who were just emerging from the isolation, poverty and suppression of the Cultural Revolution, the US was like a warm spring breeze, thawing China from the freeze of the Cultural Revolution. Consequently, people admired and imitated American thoughts and behaviours.

Those who believed that immediately implementing Western-style democracy in China would bring about all good things were no different from those who previously believed that implementing Marxism-Leninism would create a paradise on earth...

As a result, the mainstream intellectual trend in China shifted 180 degrees, from far left proletarian dictatorship and ongoing revolution, to the belief that the ultimate solution to all of China's problems was adopting Western representative politics, including the separation of powers, universal suffrage and freedom of the press and speech. There was also a theoretical trend advocating "new authoritarianism", the belief that enlightened autocracy by the elite was a necessary historical stage towards modern democracy, that it was fully evidenced in human political history and could not be bypassed.

Those who believed that immediately implementing Western-style democracy in China would bring about all good things were no different from those who previously believed that implementing Marxism-Leninism would create a paradise on earth - it was fundamentally romantic idealism, and would inevitably lead to disaster. They even cited Hitler as an example to show that elections without social and cultural conditions would lead to even more terrifying populist leaders, who would exercise absolute power, completely destroy democracy, and bring the danger of terrible domestic and international wars, all in the name of people's trust.

Nevertheless, the new China was established based on Marxist-Leninist armed revolution. And if liberation of thought led to the opposite of Marxism-Leninism, would it undermine the legitimacy of the regime, leading to severe chaos?

While this "new authoritarianism" was rejected by mainstream academia for sounding too conservative, after the 1990s it became the mainstream trend in Chinese academia and the theoretical basis for Chinese governance.

In the late 1980s, China's reform policies faced major challenges. Deng Xiaoping proposed "socialism with Chinese characteristics", and the definition of "Chinese characteristics" would be defined by practical outcomes, which is the essence of the "white cat, black cat" theory (it does not matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it can catch mice).

Nevertheless, the new China was established based on Marxist-Leninist armed revolution. And if liberation of thought led to the opposite of Marxism-Leninism, would it undermine the legitimacy of the regime, leading to severe chaos?

A chain reaction

While rural economic reforms were tremendously successful, subsequent urban and corporate reforms resulted in extreme chaos. Given that the core of reform was releasing public resources and administrative authority, in practice this inevitably led to political elites and their relatives using privileges for business, misappropriating public assets or engaging in corruption.

Deng Xiaoping advocated that reform policies should allow some people to get rich first, but those who became wealthy were the corrupt bureaucratic privileged class, the very group the Communist Party aimed to overthrow in the revolution.

As for civil society, grassroots commercial activities became more vibrant, but they were mostly low-quality individual enterprises engaged in touting rides, hawking pirated videos, peddling cheap goods in Guangdong, running the underground sex industry, selling counterfeit foreign goods and various other illegal activities.

These people made a fortune with their daring ways - their income was tens or hundreds of times those of doctors, professors and professionals. Their lifestyles were extravagant and their behaviour crass, much to the public's dismay. The corruption and extreme wealth inequality caused by the second phase of reforms eventually sparked large-scale mass protests in the spring of 1989, with the iconic Goddess of Democracy erected in Beijing's Tiananmen Square.

In the early hours of 4 June, soldiers and tanks of the People's Liberation Army moved into the square to suppress the protests, marking a tragic page in the history of new China. The Tiananmen Square incident was broadcast on television and shook the world, triggering a shocking chain reaction on the other side of the globe.

In October, a cheering crowd in East Berlin broke down the Berlin Wall with picks and shovels, symbolising the beginning of a new era. The following year, the two Germanys were reunified through democratic elections. In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed after a failed coup by the conservative camp. Crowds toppled the giant statue of the founder of the Soviet Communist Party; and in the place where the socialist revolution originated, the people came together to end an unprecedented experiment in human social systems that had lasted nearly 70 years. Communist countries in Eastern Europe, previously supported by the installed Red Army, also changed, and the winners and losers of the ideological war were set.

From the Tiananmen Square incident to the collapse of the Soviet Union, these were significant challenges for China. CCP General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, who was sympathetic to the student movement, was replaced by the more neutral Jiang Zemin. However, discontent within China persisted, and Western countries imposed sanctions on China. Meanwhile, the communist ideology lost its practical legitimacy and became a purely theoretical concept. The atmosphere in China became closed, and the intellectuals argued over whether reform was considered socialism or capitalism.

... the dissolution of the Soviet Union seemed to lift the ideological shackles on China, as so-called Marxist-Leninist dogmas such as class struggle, collective farms and absolute public ownership easily fell away.

Removal of ideological shackles

At this time, Deng Xiaoping showed his political style of remaining calm and steady in a crisis, as China kept a low diplomatic profile and avoided confrontation with Western countries. For many Communist revolutionaries, the Soviet Union represented their life's pursuit; now that it had disappeared overnight, they were left with unspeakable sorrow and emptiness, and a sense of embarrassment as well as belittlement and ridicule of all their sacrifices. However, Deng did not show any dejection. On the contrary, the dissolution of the Soviet Union seemed to lift the ideological shackles on China, as so-called Marxist-Leninist dogmas such as class struggle, collective farms and absolute public ownership easily fell away.

Now, Deng could drive the reform agenda without ideological constraints, and he restarted reform efforts with his Southern tour of 1992. Restrictions on private businesses were significantly relaxed, as many intellectuals ventured into private enterprises and the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) moved towards privatisation. As for unprofitable SOEs, the government allowed them to go bankrupt and shutter. China experienced a boom in entrepreneurship, with almost everyone wanting to start a business and make money - wholesale clothing, factory outsourcing, running eateries, tourism, trade, acting as intermediaries for labour, handling foreign visas, and so on - any opportunity to make money would do.

A flood of material desires - suppressed for 30 years - burst forth overnight. Coupled with China's traditional emphasis on commerce and the influx of investments from overseas Chinese all over the world, this yielded the most spectacular results of capitalism in China, as its economy grew exponentially, reaching almost the limits of human achievement.

However, capitalism also had its harsh side. Large, inefficient enterprises closed down or downsized, causing millions of employees to lose their jobs with limited compensation, forcing them to seek alternative employment. Most of these workers were middle-aged or older with nowhere to go, resulting in deep public resentment.

The government did not hold back in closing or downsizing large SOEs that lacked efficiency, providing compensation to laid-off workers. At the same time, massive investments were made in building infrastructure in major cities, including modern airports, highways, high-speed railways, subways, roads, shopping centres, and sports stadiums. In terms of funding and tax rates, the government fully supported local private entrepreneurs to create economic growth, stimulate consumption, and spawn service industries such as finance, tourism and entertainment.

The idea was for the government to remove unnecessary burdens on enterprises, and then use manufacturing as an engine to help the economy get off the ground, by creating massive employment opportunities and consumer capacity to absorb the unemployed groups leaving SOEs. This took about 15 years; initially, there were numerous social challenges, but these were gradually ironed out. This might sound simple, but China is possibly the only country in the world that could achieve this with its highly organised political and social system.

By the mid-2000s, the huge ship that was China had finally changed course and was moving forward at full speed. Its speed and force would quickly make it clear that its development would be even more breathtaking.

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)