Lin Liyun: The legendary interpreter for Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai [Photo story]

Lin Liyun was born in Taiwan, grew up in Japan, and eventually found herself in the company of none other than Chinese leaders Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, as she interpreted for them at various events and occasions. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao gathered Lin's oral history, and now sets out her fascinating story.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

Taiwan previously came under 50 years of Japanese colonial rule, while China also suffered from Japan's military aggression; but while Taiwan and mainland China are one people, they belong to different political camps. Time and events have shaped the complex relationship between Taiwan, mainland China and Japan.

In my journalistic career, I once interviewed a Taiwanese woman with a unique background - she was educated in Japan, and later became the Japanese interpreter for Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, participating in the negotiations for the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Japan in 1972.

From 2002 to 2005, I recorded Lin's oral history in Beijing, documenting plenty of firsthand textual and pictorial materials.

In her later years, she returned to her hometown in Taiwan and was warmly received by the community. Among the Taiwanese I interviewed who lived through that era, none was as legendary or representative of the times as her.

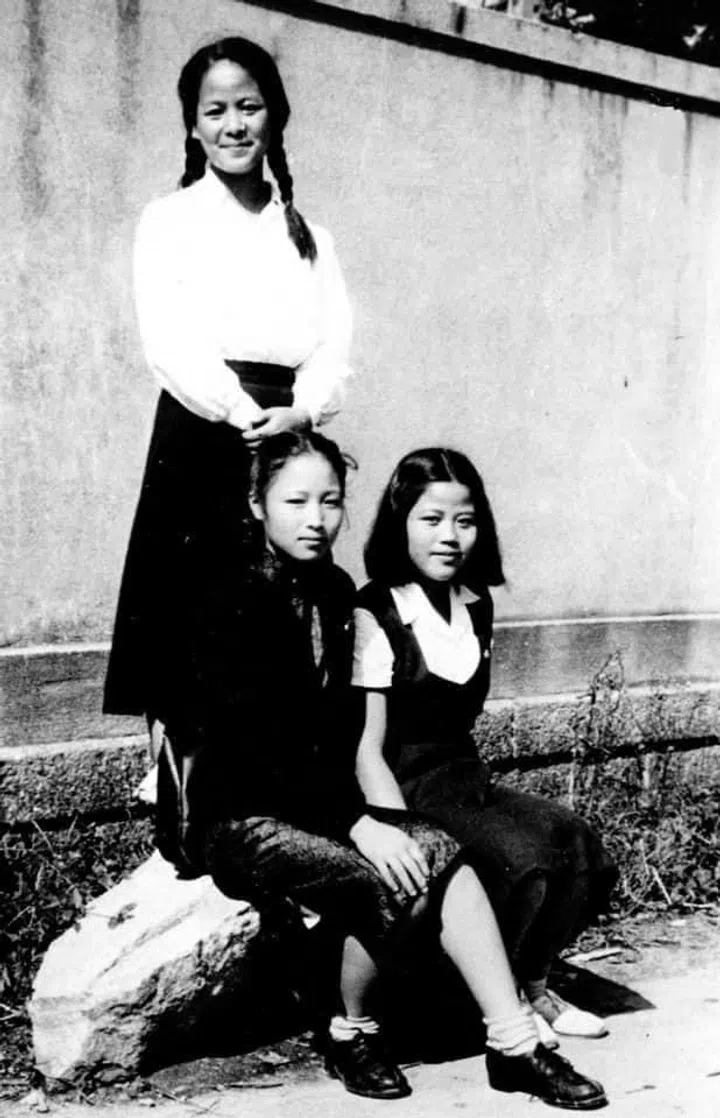

Her name is Lin Liyun (林丽韫). She was born in Qingshui district, Taichung in 1933, and later moved to Japan with her parents. After graduating from high school, she went to university in Beijing and joined the civil service in mainland China, becoming the personal Japanese interpreter for the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), participating in many significant historical events. From 2002 to 2005, I recorded Lin's oral history in Beijing, documenting plenty of firsthand textual and pictorial materials.

Growing up with a strong sense of national consciousness

Lin was influenced by her family, developing a strong sense of national consciousness from an early age.

Her family moved to Taipei, where Lin attended Yongle Elementary School. When she was nine, her father relocated the family to Kobe, Japan. After Japan's defeat in World War II, Taiwanese in Japan regained Chinese nationality and held documents from the Republic of China (ROC).

However, after the February 28 incident of 1947 - an anti-government uprising in Taiwan that was violently suppressed by the Kuomintang-led nationalist government - the Taiwanese overseas community quickly leaned towards the left, and many people hoped that the emerging CCP would bring positive changes.

The Kobe Chinese School, where Lin Liyun studied, was a stronghold of socialist thought. In post-war Japan, much had to be done, and ideologies clashed. When the CCP established socialist China in 1949, showing its vigorous revolutionary spirit, it had a tremendous impact on the Taiwanese psyche.

Many young Taiwanese intellectuals aspired to contribute to building a new China, and the CCP also called on overseas Chinese youth to return to mainland China and join in these efforts. About 3,000 Taiwanese youth in Japan responded to the call, overcoming diplomatic obstacles to return to mainland China.

Filled with ideals, the 19-year-old Lin Liyun also bade farewell to her family and went to mainland China, enrolling at Peking University. One year later, she happened to be selected by Liao Chengzhi, who was responsible for Japan-related work in the CCP Central Committee, to assist in receiving groups from Japan.

However, Lin Liyun, who participated in the negotiations as Zhou's interpreter, revealed some details for the first time in my interview with her.

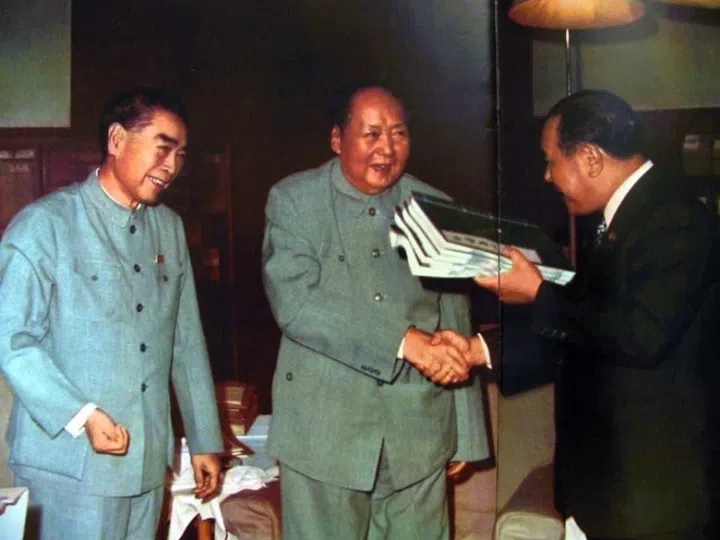

In 1954, 22-year-old Lin Liyun joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Due to her outstanding performance, she gradually took on greater responsibilities. By the time Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei visited China, she had nearly 20 years of experience in dealing with Japan, being the interpreter for Chinese leaders Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai.

Various accounts have emerged about the negotiations between China and Japan on normalising relations, including what happened behind the scenes, while the Japanese government has already made public the content of the discussions. However, Lin Liyun, who participated in the negotiations as Zhou's interpreter, revealed some details for the first time in my interview with her.

Impressions of Zhou Enlai

She said: "Premier Zhou slept in the morning, woke up at noon and then worked all day and into the night. When we hosted Tanaka, the premier's office said, 'No more briefings after 10pm.' This meant adjusting to match Tanaka's habit of rising and retiring early. However, in reality, it couldn't be done. Premier Zhou would sometimes request for materials even in the middle of the night.

"Premier Zhou worked very hard during the diplomatic negotiations because some details were not fully negotiated before Tanaka's visit. So, there was always some confrontation during the negotiations. The most intense confrontation between the two sides was about the 'one China' issue. Eventually, the solution was for Japanese Foreign Minister Masayoshi Ohira to publicly announce the abolishment of the Treaty of Taipei."

Lin gave a nuanced description of Zhou's diplomatic style. She said: "Premier Zhou was principled yet flexible in diplomacy. The most important aspect of his diplomatic style was to convince others through logic rather than a bullying tactic. He adhered to principles but sought common ground while respecting differences, by which he gained consensus and removed dissent. Premier Zhou was truly remarkable in this aspect."

As for interesting anecdotes away from the negotiation table, Lin gave an example to illustrate Zhou's sensitivity to detail. She said that after the negotiations and before Tanaka and his delegation returned to Japan, the Chinese side held a farewell banquet in Shanghai, where Ohira, happy that the job was done, went around toasting each table.

Zhou asked Lin to accompany him over. Ohira first toasted the tables where the Japanese guests were sitting, and Zhou also went to toast his Japanese friends. After the toasting, Zhou invited Foreign Minister Ohira to return to their seats together.

Lin felt Zhou had observed that if Ohira went round toasting every table, he might get drunk and lost his composure. To Lin, the incident demonstrated Zhou's care and concern for others. While he was a high-ranking leader, Zhou was more meticulous than the service staff.

Lin herself even came in for criticism at one time.

On the tenth anniversary of the death of Japanese Socialist Party leader Inejiro Asanuma, his wife visited mainland China, and Zhou received her at the Great Hall of the People. It was cold as he waited at the north gate of the Great Hall, and he turned to ask Lin: "Lin, what do you think Mrs Asanuma will wear?"

Lin had seen her at the hotel earlier in the day wearing pants and a warm jacket as Japanese women generally wear in cold weather, so she replied: "I think she will be wearing pants. The weather is so cold, she probably won't wear something as troublesome as a kimono."

However, Mrs Asanuma turned up in a formal kimono, according to Japanese etiquette. Kimonos are not easy to walk in, and she climbed the stairs at the north gate one step at a time in the wind. Zhou turned to Lin and said: "You and your subjectivity, Lin!"

He immediately instructed the security guards to move Mrs Asanuma's car to the underground garage so that she could leave through the basement after.

Lin felt humbled and regretful. It did not occur to her that Zhou was actually concerned about Mrs Asanuma's comfort and well-being in the cold as Lin herself was not paying attention to that. In Lin's view, Zhou was mindful of details despite being a very busy man, and one thing she learned from him was to be attentive and caring towards others.

Mixed receptions and suspicions during the Cultural Revolution

Following the normalisation of relations between Beijing and Tokyo, Lin visited Japan several times as part of Chinese delegations, during which she reunited with her family in Kobe. The Taiwanese community in Kobe felt closely connected to her; they were proud of the young Taiwanese girl who left Kobe and returned to Japan as a senior diplomat from Beijing with high-level treatment from the Japanese government.

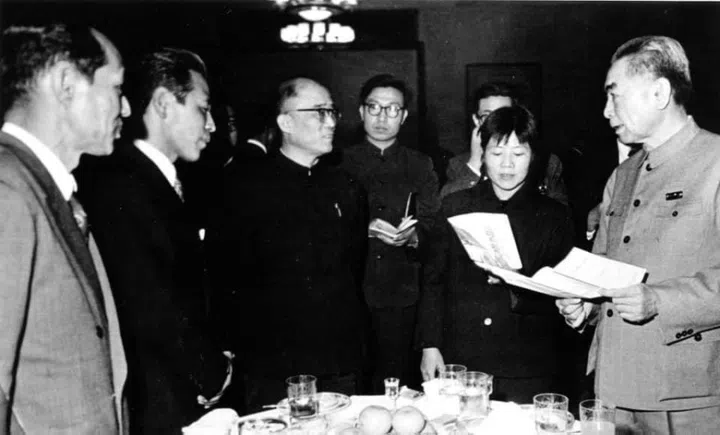

The reaction from the Japanese news media was also multi-faceted. They were not only curious about Lin, but also affectionately regarded her as one of their own, as she had moved onto the world stage from Japan. While Lin had to keep a low profile in her work, her frequent appearance in news photographs next to Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai naturally attracted attention.

In 1976, when Zhou Enlai passed away, Lin said: "I cried for days, mourning like my own parents had died. I lost two kilograms. When the masses came to offer their condolences, we took turns standing guard by the casket. Indoors and outdoors, everyone was crying, even when we went home after our shift."

With Zhou's passing, Lin gradually stepped back from diplomatic work. In 1981, she devoted herself to organising the All-China Federation of Taiwan Compatriots (中华全国台湾同胞联谊会) and became its first president. During the Cultural Revolution, people with overseas connections were hit badly, and Taiwanese were disastrously affected by suspicions of being "Kuomintang agents" - many Taiwanese who had enthusiastically returned to the motherland were persecuted. Lin's first task was to determine the actual number and situation of Taiwanese compatriots nationwide, overturn wrongful cases, and help Taiwanese get back to their normal work and lives.

On the other hand, under Deng Xiaoping's new open-door policy, Lin also hosted visiting Taiwanese, including various political figures.

Reunited once again

In 1989, after nearly 40 years of separation, Lin received family members from Qingshui for the first time at the Kunlun Hotel in Beijing, a touching scene of a Taiwanese family reuniting after half a century.

The elders of the Lin clan could never have imagined that the little girl of the family would become Zhou's most trusted Japanese interpreter, who not only traversed the Taiwan Strait but also confidently navigated China-Japan diplomacy. The family laughed and talked endlessly in the hotel room, just like thousands of other Taiwanese people who had similar experiences.

However, Lin's story did not end there. Due to her high-level position in mainland China, her requests to return to Taiwan were not approved by the Taiwanese authorities for a long time.

The brief reunion left Lin Liyun with mixed emotions; she couldn't believe that even after more than 50 years of separation, they still considered her a member of Qingshui.

In 1999, Lin finally visited Taiwan as the leader of a minority ethnic group delegation, during which she made a quick trip to Qingshui to meet the Lin clan.

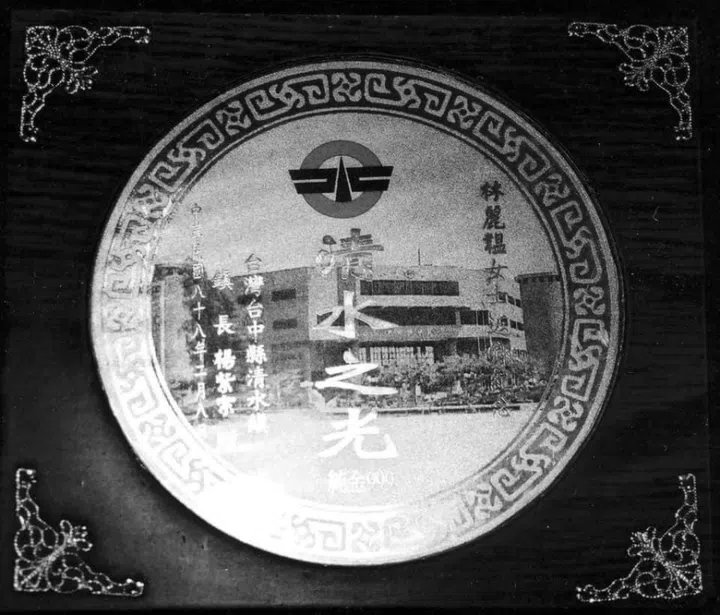

Fifty years seemed to have flown by. Like any Chinese person returning to their roots, Lin raised her glass and toasted the lively and carefree gathering of relatives and friends. The brief reunion left Lin Liyun with mixed emotions; she couldn't believe that even after more than 50 years of separation, they still considered her a member of Qingshui.

After returning to Beijing, Lin Liyun received a card from her fellow townspeople in Qingshui, which seemed to be the perfect footnote to the legend of this daughter of Taiwan. It read: "You may have been away from your hometown for 59 years, but we still hold you dear in our thoughts. Wisdom and perseverance have added some grey hairs to you, the elder sister from our hometown; your life's journey and extraordinary achievements, as well as your love for your hometown and its people, have earned our infinite admiration..."

"I believe what I have done is the best choice I could make in my life." - Lin Liyun

Over three years of oral history interviews with Lin, I also assisted Japanese author Yoshihiko Honda in writing a related book, which was published in Japan. At the same time, I arranged for Japan's Fuji Television to conduct an exclusive interview with Lin in Beijing and produce a special programme, which enjoyed great viewership ratings.

The government and diplomatic circles in Japan all know of this legendary Taiwanese woman who has covered Taiwan, Japan, and mainland China. During our intensive work, we formed a deep bond and treated each other like siblings. In 2009, amid the easing of cross-strait relations, Lin and a group of elderly Taiwanese returned to Taiwan from Beijing, and the townspeople of Qingshui welcomed them at the airport in a touching scene. Due to circumstances, we were unable to reunite in Taipei, but we would still exchange Lunar New Year greetings.

Over time, we lost contact, but I often think of her, especially when I'm organising the old photos she provided, some of which make me pause and gaze at them for a while. No matter which influential figures Lin Liyun has encountered, the grand occasions she has witnessed, or the high ranks she has held, in my mind, she will always be the fresh, sweet young lady from Qingshui.

My job is to faithfully record history, leaving it for future generations to study and reference. I try my best not to make personal judgements about her, and I will conclude with Lin's own words: "I believe what I have done is the best choice I could make in my life."

Related: [Photo story] The Dixie Mission during WWII: First contact between the US and the CCP | When the arts is more than politics: Reflections on the 50th anniversary of the Philadelphia Orchestra's China tour | Chinese researcher: Is it appropriate to address Mao Zedong as 'the older generation' of leaders? | Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping - Five generations of CPC leaders | From Mao ideals to the American dream: What China's 'sent down youths' sacrificed to chase a better tomorrow

![[Photos] Fact versus fiction: The portrayal of WWII anti-Japanese martyrs in Taiwan](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/3494f8bd481870f7c65b881fd21a3fd733f573f23232376e39c532a2c7593cbc)